Visiting the Laing's new exhibition - magnifying glass to hand

Bewick and Beatrix in miniatures show

A timely reminder that I really do need to go to that optician that advertises amusingly on the telly comes with the latest ticketed exhibition at the Laing.

The clue is in the title, Miniature Worlds.

It’s more than a clue really. You can’t argue that they’re hiding it from us, the fact that this is one where the full glory of the art is revealed through pressing your nose up close rather than taking several strides back.

At first glance, once you round the enormous introductory board, it’s not so much an in-your-face explosion of colour as a succession of monochrome smudges.

But magnifying glasses are provided – which I don’t think I’ve seen in the gallery since its last Thomas Bewick exhibition maybe a decade ago.

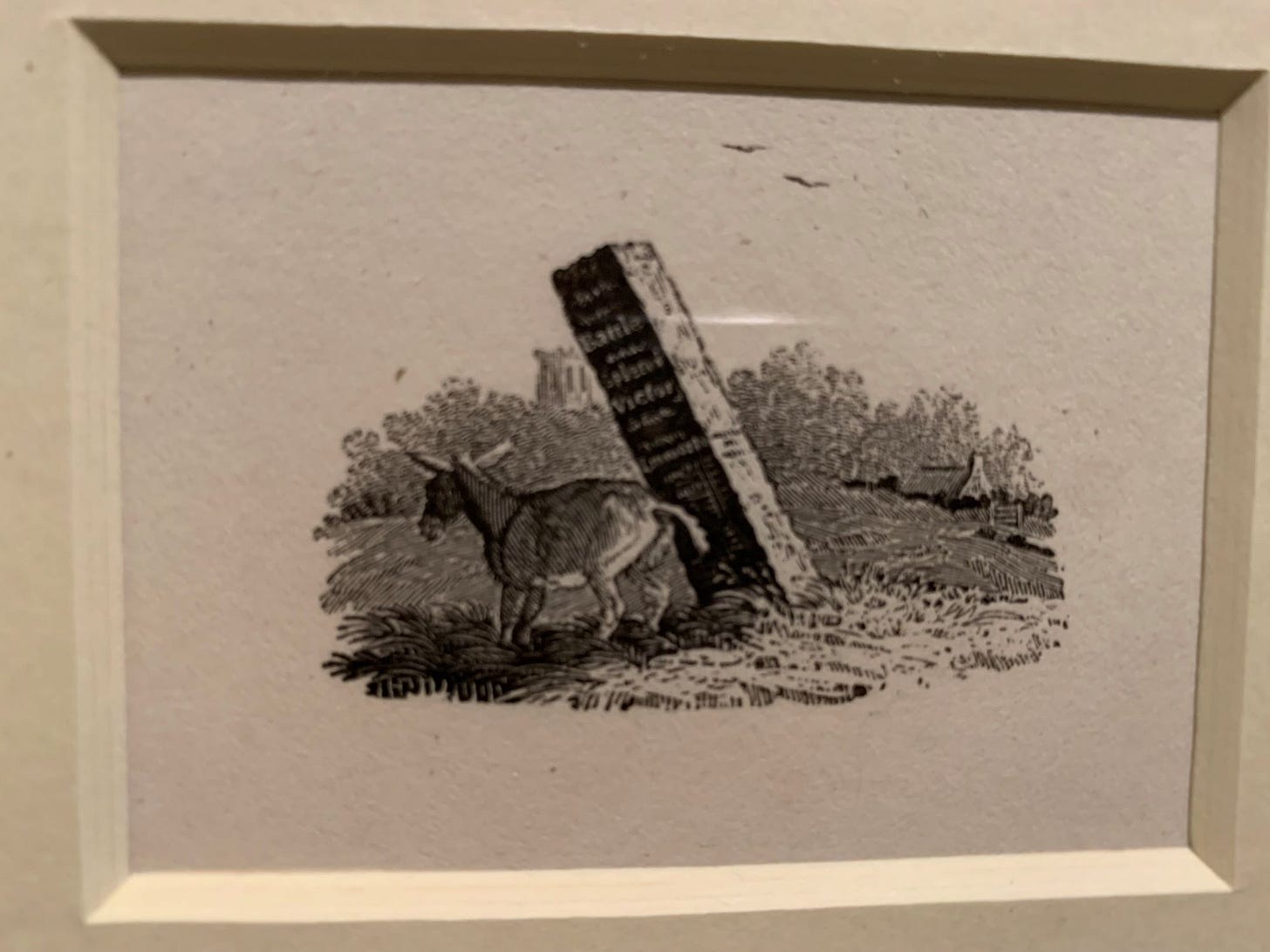

It’s Bewick, of course, who opens the show. He was a Tyneside genius, the late 18th/early 19th Century master of the woodblock print whose every tiny creation was indeed a mini-masterpiece.

He specialised in tailpieces, little illustrations at the end of a book, but re-named them ‘tale-pieces’ because they were more than illustrative.

Each one he created in his Newcastle workshop was a potential scene-stealer with its own story to tell.

There are examples – from the Laing and national collections – of his illustrations for the famous two volumes of A History of British Birds.

A copy of the second volume is open at pages 104 and 105.

There, after a long and earnest discussion of some migrating species (“They leave England in the autumn, but whither they go is not particularly noticed.”) Bewick depicts a man pissing against Hadrian’s Wall.

Bewick’s sense of humour, plus his moral sensibility, is evident again in his tale-piece engraving of a donkey scratching its bum on a war memorial. Such is life.

Also on show in this first of two rooms are tiny (of course) watercolour paintings by Luke Clennell, Bewick’s talented apprentice who was responsible for some of the more rudimentary tasks in the studio.

There’s a pencil and watercolour drawing by Northumberland-born John Martin called Marcus Curtius, illustration for a story in which the Roman warrior sacrificed himself to save the city by riding his horse into a chasm.

It’s said that Martin, Bewick’s contemporary, could make early Victorian gallery visitors faint with the violent drama of his work.

Drawn to the epic, you can imagine him struggling to contain himself on this small scale and possibly having to relieve himself afterwards, not like Bewick’s Hadrian’s Wall rascal but by hurling crimson paint at something similarly monumental.

There’s lots more to see before proceeding, including William Blake’s only venture into wood engraving, his beautiful illustrations for a children’s edition of a work by Virgil, and others by Turner for a book about Italy.

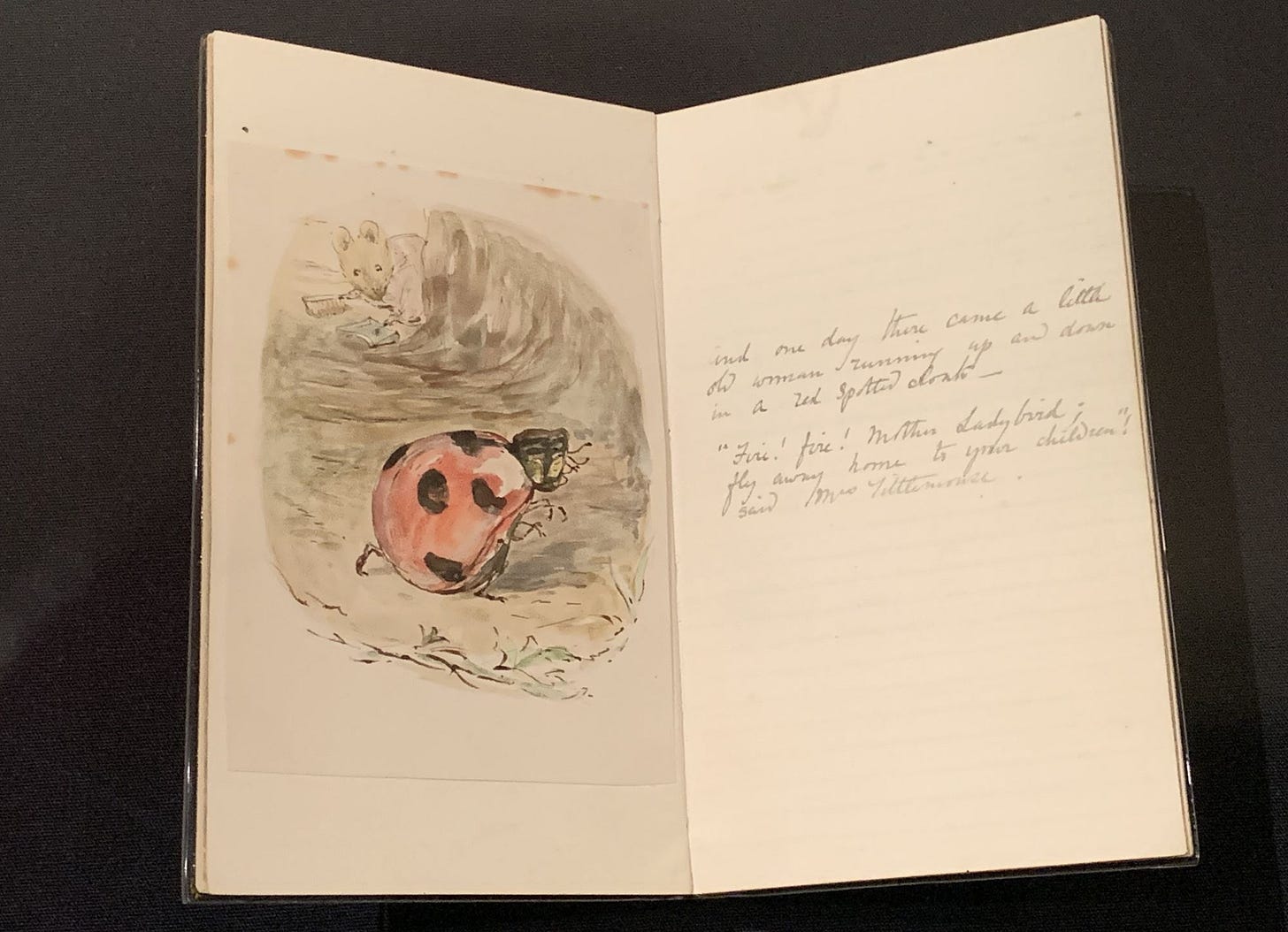

Step into the second room and you enter the world of Victorian and Edwardian book illustration with works by Beatrix Potter and others.

For many, this will stir memories of childhood. Who doesn’t love The Tale of the Flopsy Bunnies which was published in 1909 and is still in print?

Here, from the British Museum, are the artist-author’s original watercolour illustrations for the ever-popular story; and nearby you’ll see – what a treasure! – the manuscript, on loan from the Victoria and Albert Museum, of The Tale of Mrs Tittle-Mouse, published that same year.

There are works by Kate Greenaway, the Victorian illustrator whose name was remembered annually with a prestigious award for illustration until the Kate Greenaway Medal became the Carnegie Medal in 2022.

On show are some of her annual ‘almanacks’, little illustrated calendars, on loan from the Robinson Library, Newcastle University.

This bit of the exhibition, called Imagined Worlds, has a book discovery zone with some welcome comfy chairs and an overblown depiction of the Cheshire Cat, as scarily imagined by Sir John Tenniel for Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland.

It’s probably the biggest drawing you’ll see in the exhibition.

Another Tenniel illustration, showing Alice and the Red Queen, is on loan from the V&A. The caption tells us he drew directly onto woodblocks which were then engraved by the Dalziel Brothers.

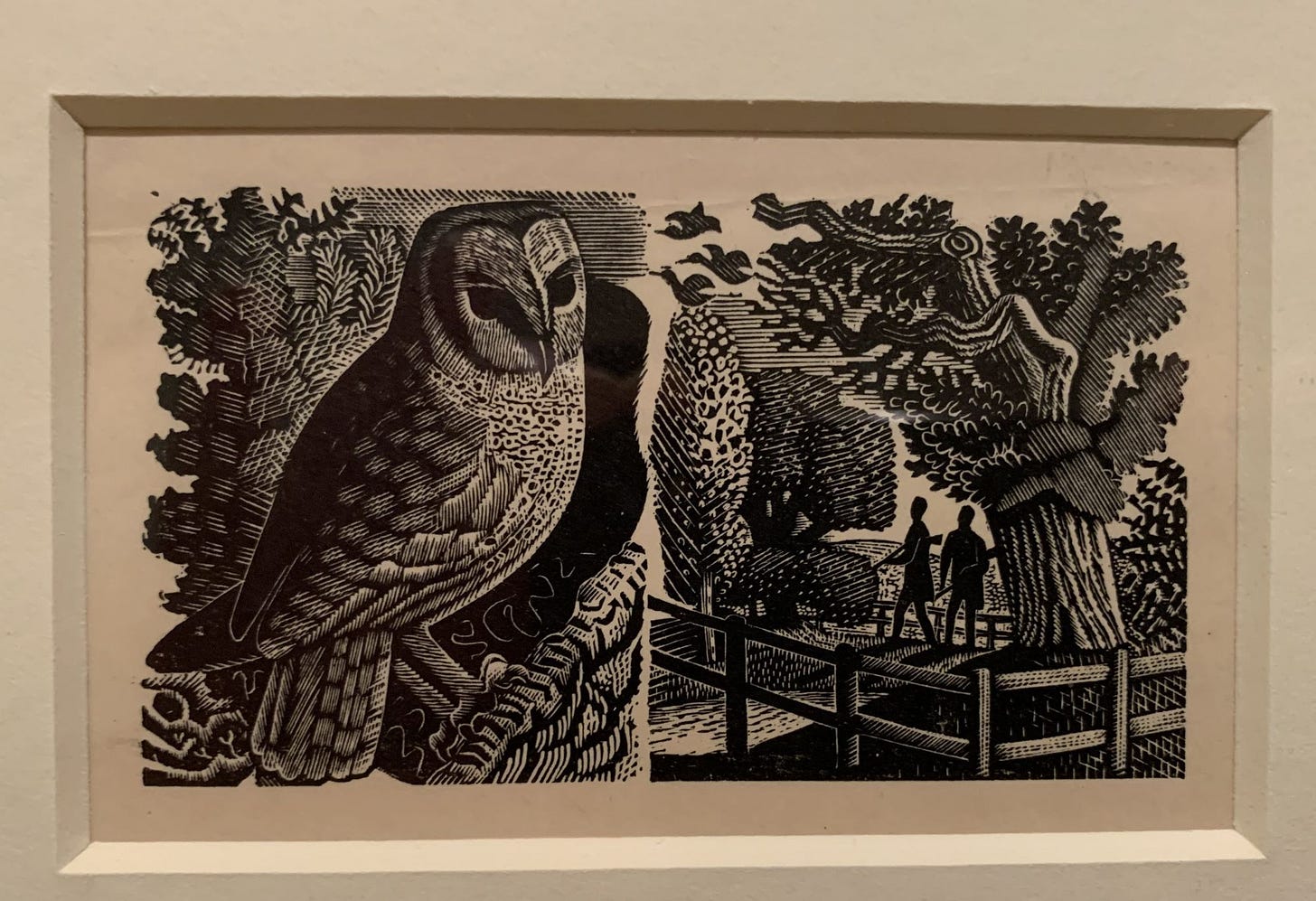

Then Modern Visions takes us to the 20th Century and some wonderfully crisp and detailed illustrations by Eric Ravilious showing scenes of nature.

I’ve always loved his illustrations but he was cut off in his prime. Having become a war artist during the Second World War, he died when an RAF plane he was flying in disappeared off Iceland in 1942.

I also trained my magnifying glass on the woodblock prints of Agnes Miller Parker (1895 to 1980), a Scottish artist and prolific book illustrator who beautifully embellished a 1931 edition of Aesop’s Fables.

Both artists could be seen to have been picking up where Thomas Bewick left off, recording nature with pleasing precision.

The far end of the second room is given over to more contemporary manifestations of the miniature.

Richard Hamilton, the pop art guru who taught in the 1960s at Newcastle University, inverted the notion of the miniature by extracting one tiny detail from a large photograph and blowing it up.

What we see is a very grainy image of a woman and a child with an inflatable toy in the sea. He called the piece, dated 1969, Vignette. If it looks like a mistake, it’s not. Apparently it was very tricky to do.

Sculptural works by Paul Coldwell fill the void between the walls and there’s a display case dedicated to the tiny but rich and vivid paintings of Joanna Whittle, including a series under the title Forest Shrine that were conceived during the Covid lockdowns.

Meanwhile a painting by Vicken Parsons confines the sky to a small wooden panel.

It hangs here in ironic counterpoint to The Angel of the North, her husband Anthony Gormley’s famous work which is about everything that this exhibition is not.

And now it’s time to put the magnifying glass back in the rack and quit peering and squinting.

Miniature Worlds is on until February 11, 2026. Charges apply but there are details of those and opening times on the Laing Art Gallery website. There is also a series of accompanying talks.