The trains that changed the world from Tyneside

How the railways changed a city - and life. Tony Henderson reports

The arrival of the railways brought change by the wagonload.

Locomotives and a rapidly expanding rail network transformed lives and economies in towns and cities across the world on the back of the achievements of North East pioneers.

That railway heritage is everywhere in the region and is especially clustered in a particular sector of Newcastle.

Now Newcastle-based railway expert and author Les Turnbull has produced a book packed with fascinating Tyneside railway facts and which doubles as a guide for a circular walk focused on the Central Station, its surrounds and the Quayside.

It illustrates how much railway history on the doorstep is largely overlooked.

Les says: “There is an enormous railway presence. There is so much railway heritage but Tyneside has neglected that heritage.”

He poses the question of what elements of the North East would feature in a short book of the history of the world.

His answer: “It is unlikely that our Roman, Anglo-Saxon or medieval treasures would appear. What would be certain to appear would be our railway heritage, for engineers from this region gave the world both the railways and the steam locomotive.

“By providing the means for people and goods to be transported quickly and cheaply, they changed the course of civilisations throughout the world.

“It is no accident that even today most of the railways of the world, including the high-speed lines of Europe and Asia, are built to a standard gauge established by the colliery railways of Tyneside.”

Robert Stephenson’s locomotive factory in Newcastle, the first railway works in the world, produced the engine and carriage for the Khedive of Egypt, which is now preserved in Cairo and is pictured outside the Central Station.

Other locomotives were built for the Tsar of Russia and for America, Africa and Asia. By the end of the 19th century the works behind the Central Station had built more than 3,000 locomotives for railways across the globe.

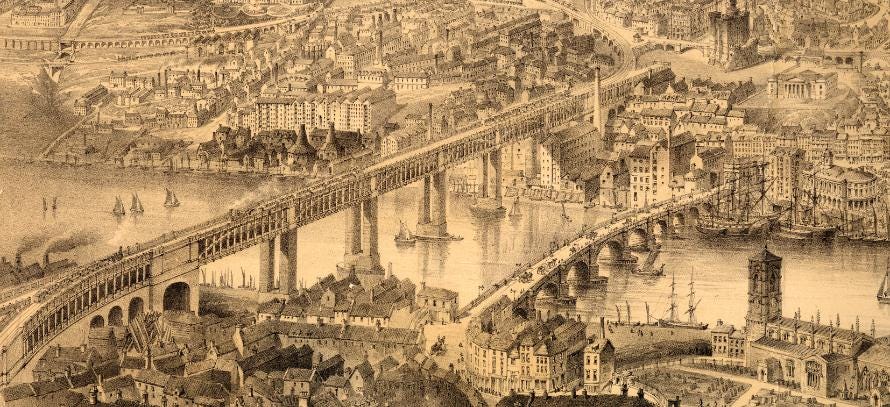

The use by Les in his book of fine detailed drawings by 19th century artist John Storey brings home the scale of the changes the railway visited on Newcastle.

One shows Robert Stephenson’s new High Level Bridge with its upper railway deck towering over the adjacent late 18th century bridge which catered for pedestrians and horse traffic and would be replaced by the Swing Bridge.

“The 18th century road bridge was the main road connecting Newcastle with London and Edinburgh - the A1 of the age,” says Les.

“It is dwarfed by the High Level Bridge where the latest technology - the steam locomotive - was in use. The architecture stated that the age of the railway had arrived and steam power was supreme.”

Les Turnbull’s book, Celebrating Tyneside’s Railway Heritage, was launched with a presentation by the author at a free public event at lunchtime today (Sept 4) at the Common Room, Newcastle - formerly the Mining Institute. It is published by the Common Room and priced at £6.

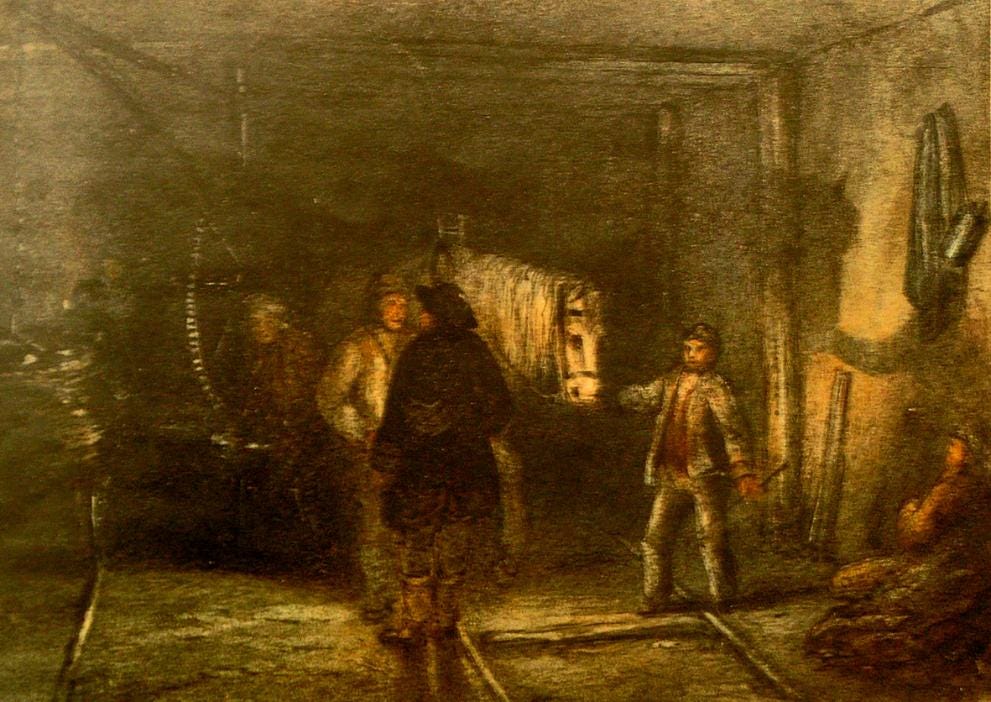

The story starts with the expansion of coal production from the 17th to the early 19th centuries, made possible by the extensive network of wooden waggonways from the collieries to river staiths, and underground in the mines.

But coal was just one commodity. Les says: “The railways were expected to transport everything, and did, from minerals to horses, cows, pigs, sheep and pigeons, to fruit, fish and flowers, small parcels and Parson’s massive turbines.”

By 1901 the Central Station was handling around 700 trains a day and up to 1,000 at peak times, with the booking office issuing over a million tickets.

In 1899, the staff of more than 500 dealt with 8,969 dogs, 8,469 horses, 93,376 cans of milk and between 5,000 and 7,500 parcels a day. Opposite the parcels depot in Westgate Road there was even a horse hotel.

Life would never be the same again.