Stories from behind prison walls form part of Postgraduate Research Conference

Tony Henderson reports on the hard life and times of North East’s jail birds

If life was hard for men in the 19th century coal mines and heavy industries of the North East, it certainly wasn’t any easier for many women.

With few female job opportunities, it could be a life of struggle for those who were not supported by a man or wider family.

Now a study of previously unexamined parole records of 203 jailed female offenders from Newcastle, Durham and York gaols is providing a window into the lives of women in the region between 1853-1887.

Kerri Armstrong is working on her PhD on the topic at Northumbria University. “This is a vastly under-researched topic in the North East,” she says.

“My research interests focus on Victorian social and crime history. The history of crime has been dominated by the study of society through the male lens, often ignoring the different life experiences of women.”

Kerri’s presentation of her findings so far is one of seven talks at a Postgraduate Research Conference by participants from Newcastle and Northumbria universities, organised by the Society of Antiquaries of Newcastle upon Tyne (SANT) on Saturday (February 1).

The aim of what is the first in a series of annual events is to showcase new work on the history and archaeology of the North East.

The free event starts at 9.30am in the Keeton-Lomas lecture theatre, Armstrong Building, Newcastle University.

“The parole records contain so much information on the lives of the women and some run to around 20 pages,” says Kerri, who has an MA in history after graduating in business studies. She spent seven years working in business before returning to university and a PhD.

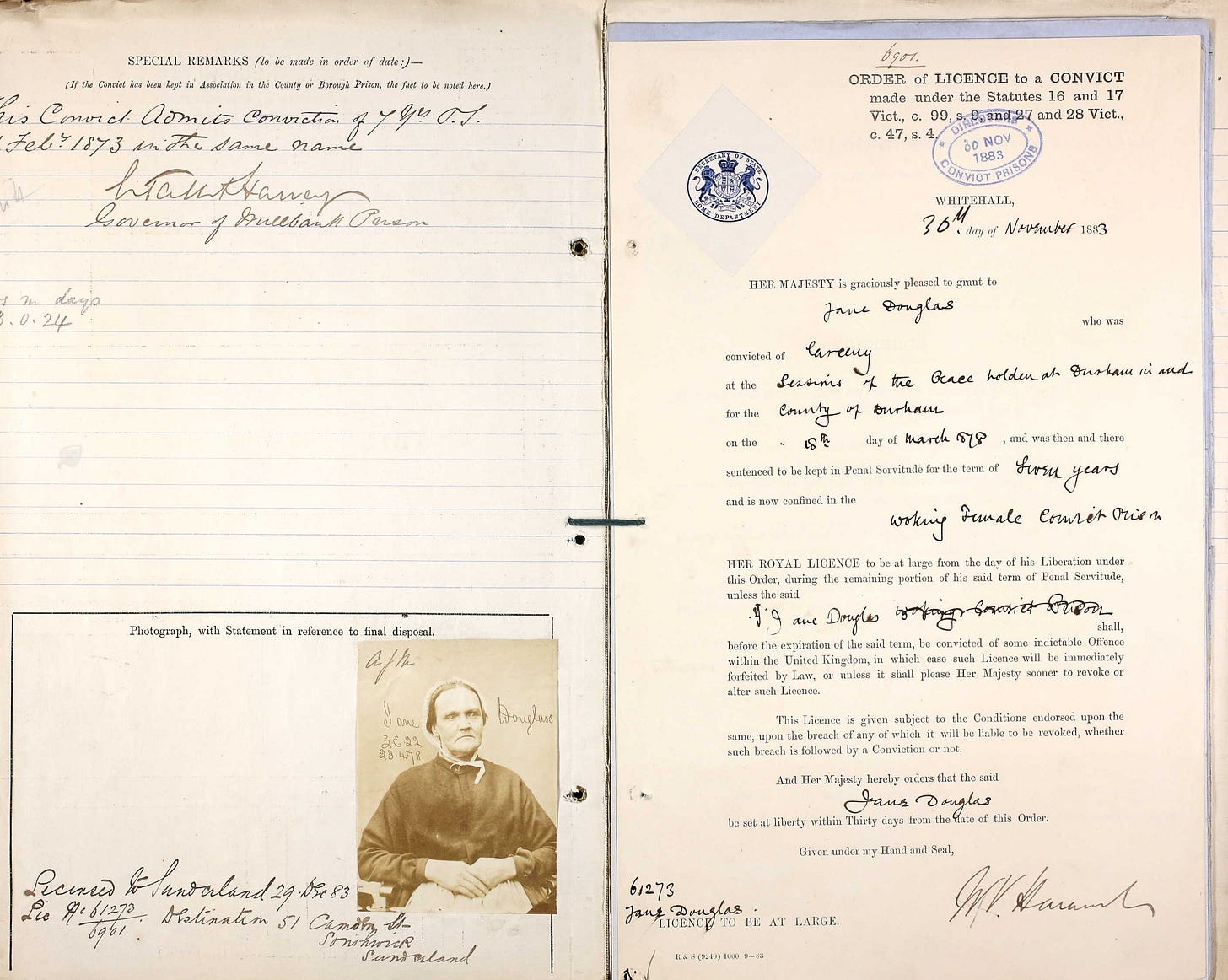

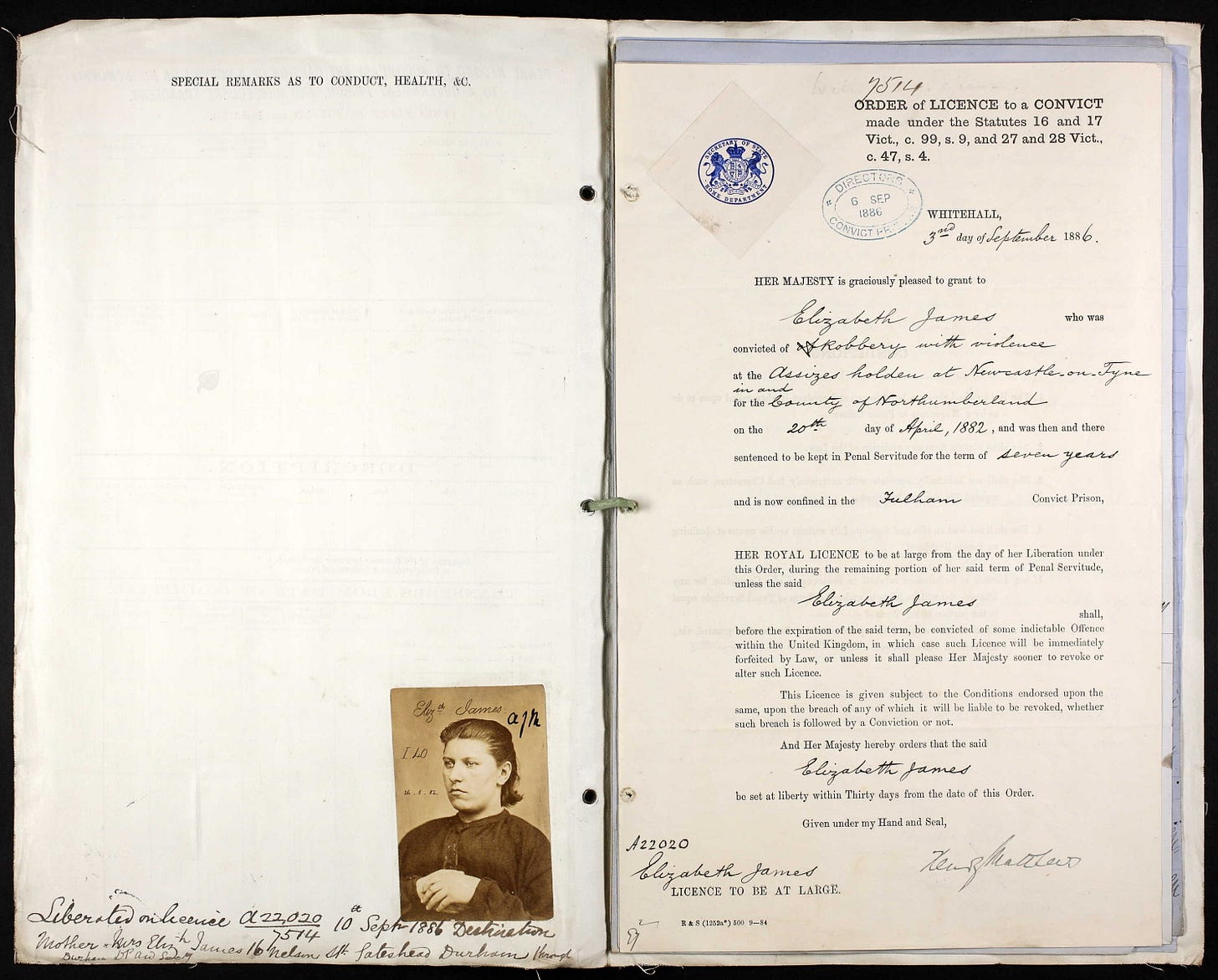

“The parole records include an amazing amount of personal information such as a mug shot, details of the crimes and where the women were convicted, sometimes snippets from newspaper which reported the cases, occupations if any, if they were married or had children or close relatives, and medical information, including their weight.”

Some women lost weight during their sentences, while others gained weight, probably because the food in jail was more regular and better than that available in their lives outside.

“The Victorians loved collecting data and we can learn so much about the women’s characters,” says Kerri.

The system Kerri is studying was created after transportation of convicts to locations such as Australia was ended.

Convict prisons were built, mainly in London and the south. Women spent the first six months of their sentences in a local prison, like Newcastle or Durham, where they spent up to 20 hours a day alone in a cell with silence enforced.

They were them transferred to a convict prison with a labour regime, which ranged from laundry work to breaking rocks.

The system allowed those serving time to be released part way through their sentence on a conditional licence with their details held in their parole record.

On release they would be held in refuges for six months where they received moral education.

“They faced discrimination and prejudice because they did not meet the Victorian ideal of a mother teaching children moral principles,” says Kerri.

The most common offence for women was stealing, either to literally survive or feed children, raise money to supplement what little they had, or in some cases turn theft into a form of business.

“The data is shining a light on society at both national and local level, exploring the workings of the state, health and lifestyle and their interaction with Victorian ideology,” says Kerri.

“I am examining women’s stories and experiences, reinstating their missing place in history.”