Something for everyone in the Laing’s new exhibition

How craft has been represented in art

As keeper of art for North East Museums, Esmé Whittaker is well acquainted with the Laing Art Gallery’s collection of fine art paintings and the Shipley Art Gallery’s treasure trove of 20th Century craft.

As well as being the inspiration for With These Hands, they also provided the bulk of what’s on show in the Laing’s two adjoining rooms, although there are also loans from other galleries and institutions.

“I love showing craft and fine art in juxtaposition because I think it can enhance both,” said Esmé just before the doors opened to the public.

This is an exhibition about making stuff, whether that be at home or in a workshop or factory, and whether for pleasure or out of necessity - or for someone else’s profit.

There’s quite a lot to unpick.

Themes include the relative merits of art and craft – snootiness about the latter surely died when a potter, Grayson Perry, won the Turner Prize in 2003 – and the roles of women in society.

The first room presents us with what seem to be rows of paintings of women sewing, usually in attractive settings. They don’t appear to be victims of drudgery.

The thought occurred to me that perhaps they were humouring the artists portraying them: “Well, if you must… but if I’ve got to sit here, I’ll do something useful to stave off boredom.”

The pictures we see show people making things with their hands, and while paintings obviously are hand-made, there’s that old class distinction to consider – craft rather looked down on as practical, fine art revered as intellectual.

It’s all nonsense, of course.

“There’s been a lot of craft scholarship done over the last 10 or 20 years, people reassessing craft and taking it seriously,” said Esmé.

“But as far as I know there haven’t been many exhibitions focused on the visual presentation of craft and looking at why artists were drawn to studying and depicting these subjects.

“I thought that was an interesting idea.”

It certainly throws up some fascinating juxtapositions, as with the quilted patchwork bedcover laid out beneath a painting called The Patchwork Quilt, done in 1887 by Lance Calkin and on loan from Nottingham City Museums & Galleries.

You’d swear at first glance that the quilt being stitched by the woman in the painting is the very one we see, beautifully preserved yet dating from the 1850s and signed on its underside S.A. Hutton.

But the caption tells us the quilt (from Newcastle’s Discovery Museum) is an example of industrial production.

Esmé said she didn’t set out to set to make a visual argument, pitting home-made against factory-made, because she could see that even in the latter a large degree of skill was involved.

In the second of the two rooms you’ll see that stitching was not the preserve of women and girls, despite the poignant little schoolroom samplers suggesting otherwise.

In a row of striking paintings showing craft as physical labour is Ralph Hedley’s The Sail Loft, dated 1908 and showing men working with needle and thread.

From the 1880s, we learn, the Newcastle-born artist dedicated himself to recording old skills as heavy industry began to dominate.

Esmé was drawn to the way traditional craft skills came to be romanticised in paintings.

“It’s often about nostalgia or preservation and this sense that craft is something that’s going to be imminently lost to industrialisation.

“Today there are organisations devoted to preserving heritage crafts but it’s by no means a new phenomenon.

“I wanted to show hand making as not just in opposition to industry, the viewpoint of (John) Ruskin and (William) Morris.

“You can easily overlook the dexterity involved in an industrial workplace. Even today there’s amazing hand skill in industry, whether in prototyping or finishing. I was hoping to draw out these subtleties.”

This she has done in an exhibition that is fascinating but not hectoring in tone.

You can draw a distinction – a class distinction, perhaps - between the women sewing out of necessity, engaging in ‘make do and mend’, and those for whom embroidery was a leisure activity.

But you can also see how factory work became liberating for women, particularly in wartime.

Some of the most interesting pictures are in this section.

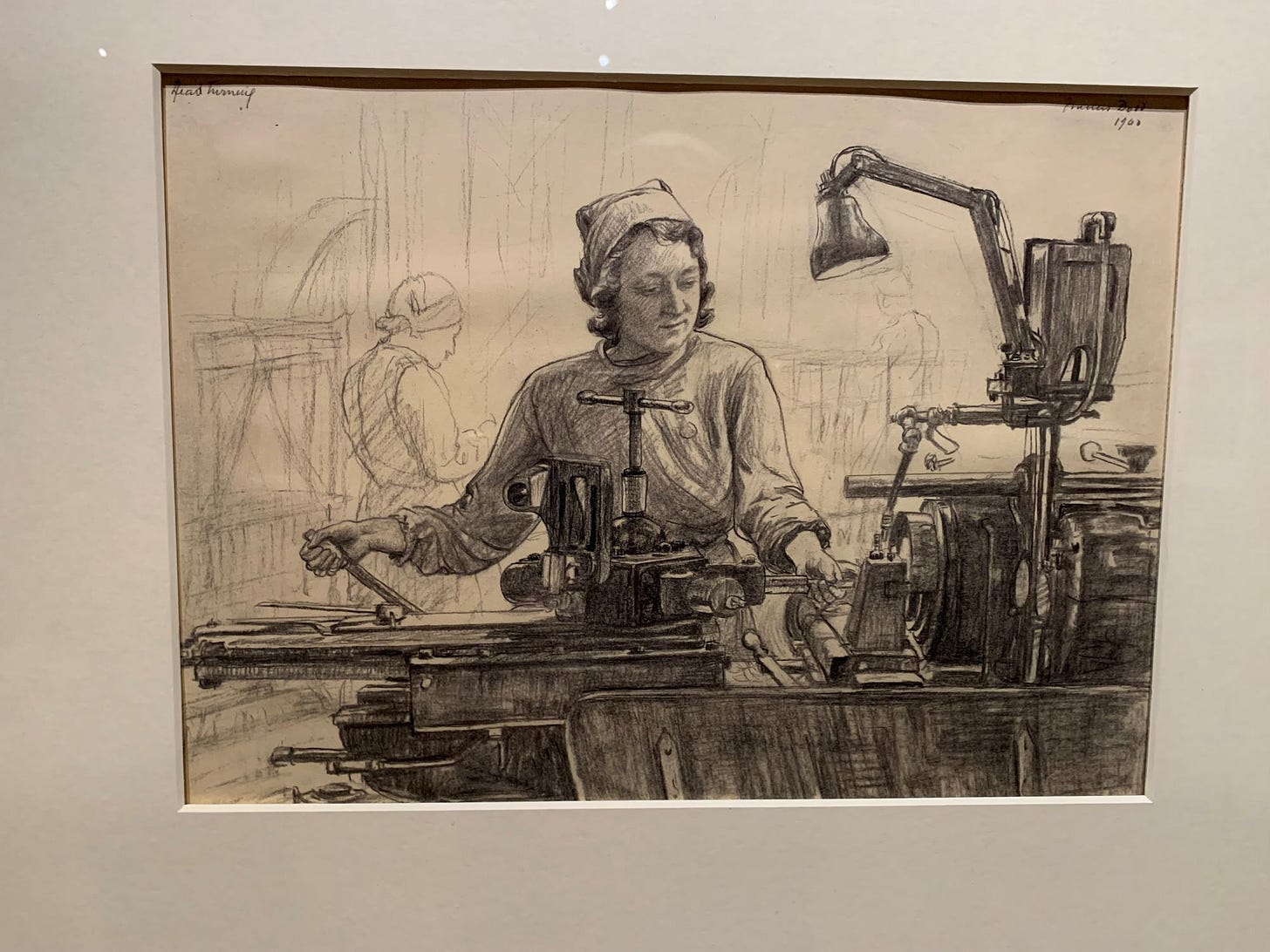

During the Second World War, Francis Dodd did a series of sketches at the Royal Ordnance Factory in Birtley when women comprised up to 60% of the workforce.

One of the machine operators he sketched is named as Alice Jane Scorer (formerly Corbett), of Sacriston, who was the factory’s works convenor and trade union shop steward.

The industrious Mrs Scorer is therefore immortalised along with a series of wartime generals and admirals and the novelist Virginia Woolf in the artistic legacy of this esteemed Royal Academician.

This is an exhibition that will appeal to the historian and to anyone who simply likes looking at beautiful and intriguing things.

Helen Baker’s sumptuous Magenta I lures you across the gallery floor. It’s one of a series of abstract paintings done by the North East artist and inspired by her mother’s and grandmother’s needlework.

She talked about the work when I interviewed her back in 2004.

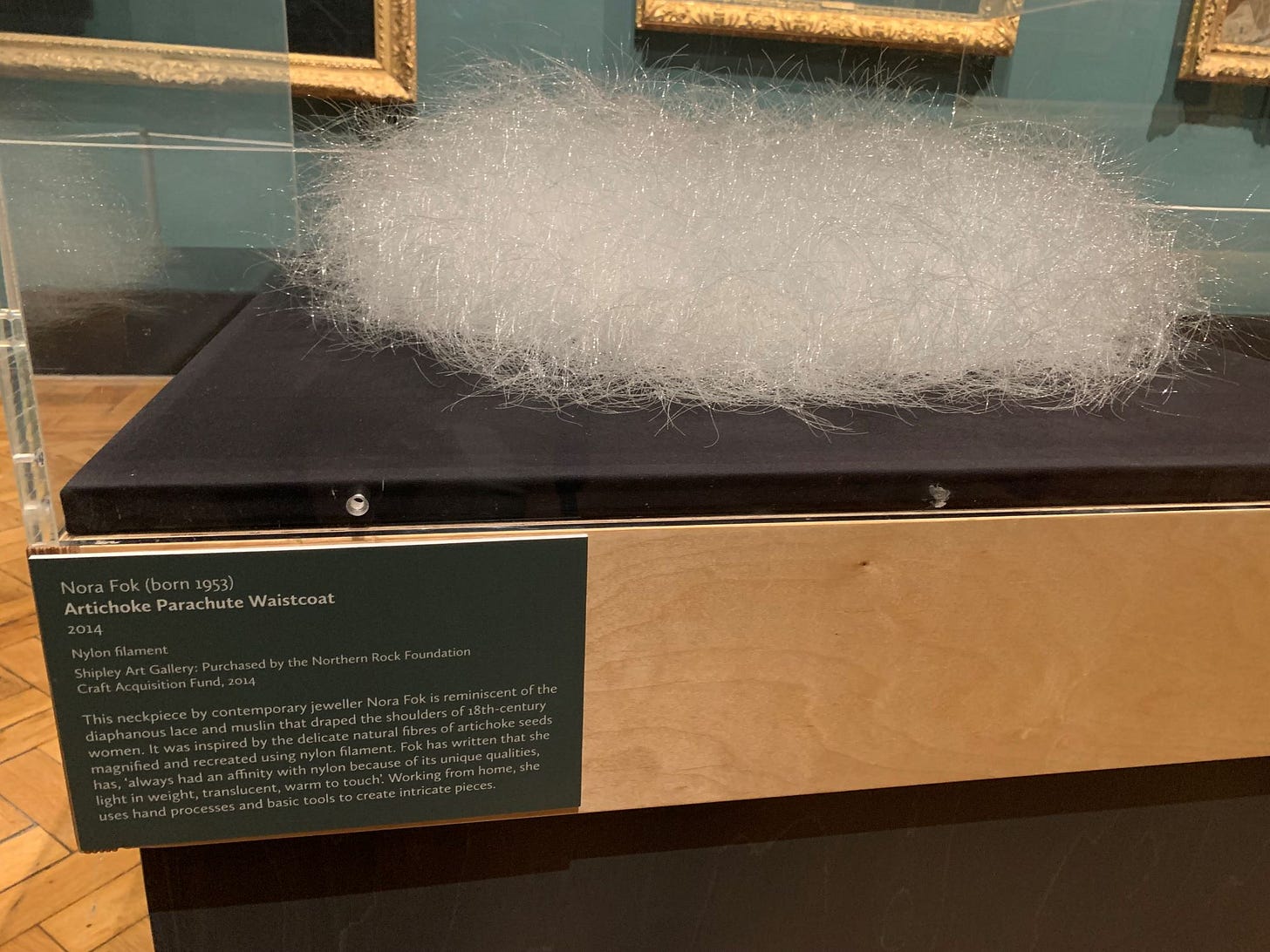

Then there’s the curious fuzzy-looking object in a display case. The work of contemporary jeweller Nora Fok, its title, Artichoke Parachute Waistcoat, belies its purpose as a neckpiece.

It’s made of nylon filament fashioned to mimic the natural fibres of artichoke seeds. Who would ever guess?

It was not the favourite item of either of the women who accompanied me around the exhibition.

Esmé went for an etching by Mary Cassatt, La leçon de crochet (The Crochet Lesson), dating from 1901 and on loan from the Victoria and Albert Museum.

Clio Lieberman, communications officer for North East Museums, picked out a loan from the Tate – a 1917 depiction of women engaged in acetylene welding by Christopher Richard Wynne Nevinson from his series The Great War: Britain’s Efforts and Ideals.

You’ll have your own favourite. It’s an exhibition with something for everyone to covet and offering plenty of food for thought.

With These Hands runs until September 27. For opening times and ticket details, go to the Laing Art Gallery website.

And you’ll find a related programme of workshops and events on offer at the Shipley Art Gallery, Prince Consort Road, Gateshead.