Roman superstition reborn as art with a climate conscience

Artist delves into the symbols which - hopefully - shielded people from life’s blows. He talks to Tony Henderson.

Life on the frontier of the Roman empire in Northumberland could be both tough and fraught with danger.

The garrison and civilian population living in and around Vindolanda fort deployed an array of symbols designed to offer protection and deliver good luck.

Now David Appleyard, Vindolanda’s 2025 Artist in Residence, has used these shields against misfortune to produce a display which links the symbols from the past with one of the dangers of today – climate change.

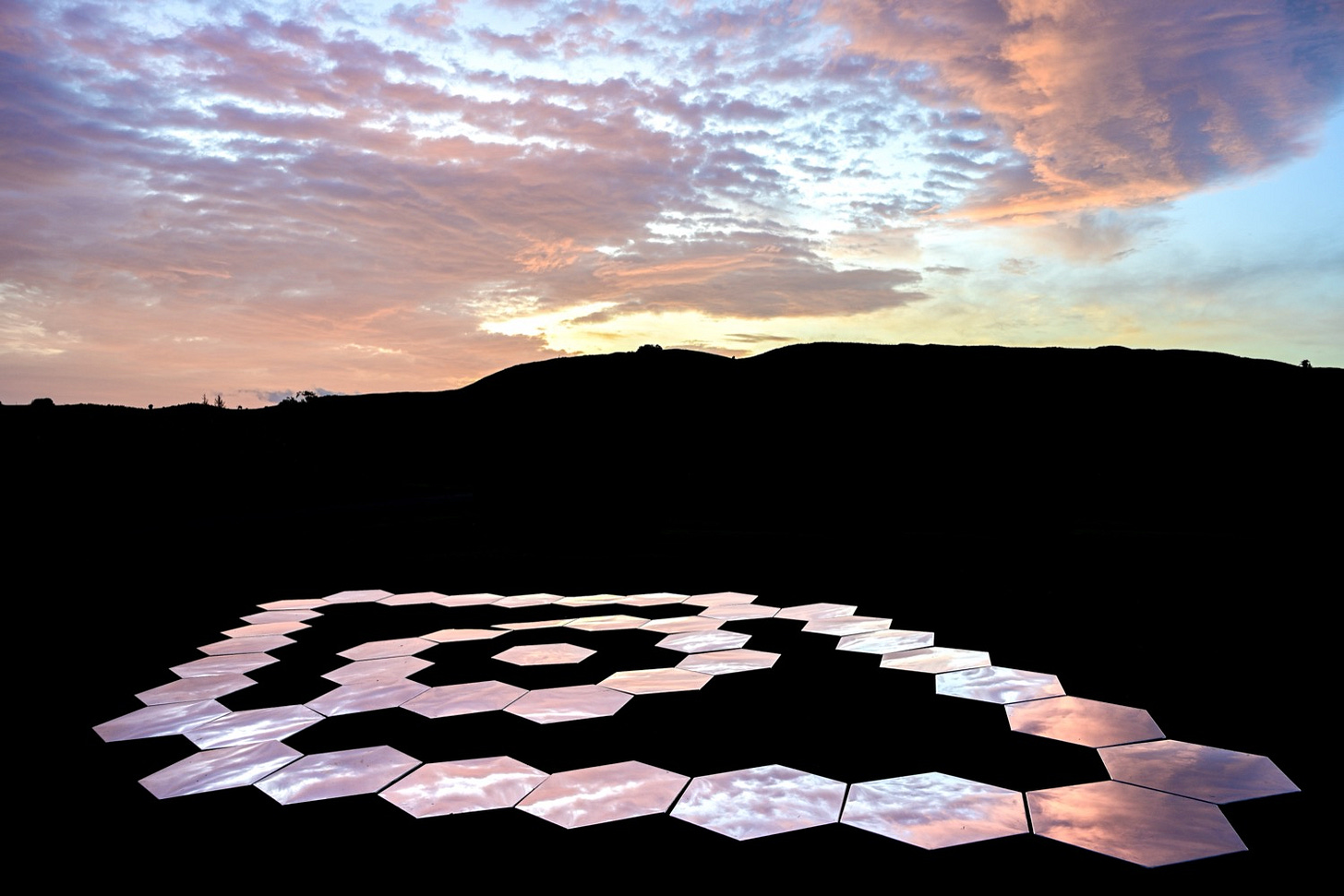

In an exercise titled Votum – a vow or a promise made to a god – David is using highly polished stainless steel shields to represent the Roman symbols at different parts of the fort site until November 2.

Votum is part of the Vindolanda Trust’s project The Land We Walk On, a three-year programme that invites artists to respond to the site’s collections and pioneering climate research at its Magna fort seven miles away.

The Trust is working with universities in a bid to measure the potentially serious impact of climate change on the buried fort remains and future finds.

In Roman Britain, protective symbols were used to ward off the malus oculus (evil eye), and were presented as offerings and inscribed into everyday objects.

The symbols in the project have been inspired by ancient artefacts in the Vindolanda collection. These original objects will be displayed in an exhibition inside the fort’s museum.

“I was drawn to the ways Roman superstition used symbols as protection, layering meaning and belief into physical form,” said David, a research-led visual artist exploring public art and heritage.

The symbols he has chosen include the Good Luck Phallus, the Bull’s Head, the Lightning Bolt, the Watchful Eye and the Wheatsheaf.

“In conversation with archaeologists and historians, I learned how Romans left votive offerings at springs, gateways, drains and altars — small gestures of hope and protection not so different from our own superstitious acts today,” he said.

“Vindolanda hums with memory. Beneath the surface lies a vast, layered history of human presence — built, dismantled, built again. It’s not just a historical site – it feels alive.”

He took up running to explore and immerse himself in the landscape surrounding the fort.

“The weather conditions were constantly changing, ranging from sleet and snow to gusty winds, yet there were also beautiful, still evenings where the sunsets felt like a reward for the effort,” he said.

“It was useful to appreciate all these conditions and to imagine life 2,000 years ago when the comforts we take for granted today were not available.

“Comforts and rewards back then were gained through a different kind of effort and a direct physical connection to the land. Being immersed in this landscape and its layered histories has been both inspiring and thought-provoking.”

He recalls being told, on a first visit to Vindolanda, that it was a place that would “get under your skin.”

He said: “It didn’t take long for it to start feeling true. At the time, I took it as a figure of speech - the sort of thing people say about places that mean a lot to them.

“But now, with the residency behind me, I can see it’s something deeper. Vindolanda really does get under your skin.”

Today, he says, we use symbols in ways ranging from branding and advertising to emojis.

“But symbols could be used as a way of getting a message out there on climate change. I find it really sobering that we risk losing knowledge and understanding of the past through the threat of climate change.”

Morag Iles, contemporary art curator at the Vindolanda Trust, said: “Hosting contemporary art at Vindolanda allows us to see our site through new and exciting perspectives.

“Projects like Votum create opportunities for visitors to connect with the collection in fresh ways, while also inspiring new audiences to explore the archaeology and heritage of Hadrian’s Wall. It is a vital way for us to bridge past and present, and to show how the ancient world continues to spark creativity and dialogue today.”

The Land We Walk On is supported by The John Ellerman Foundation, Arts Council England, and Newcastle University.