REVIEW: Basil Bunting’s Briggflatts at Hexham Abbey Festival

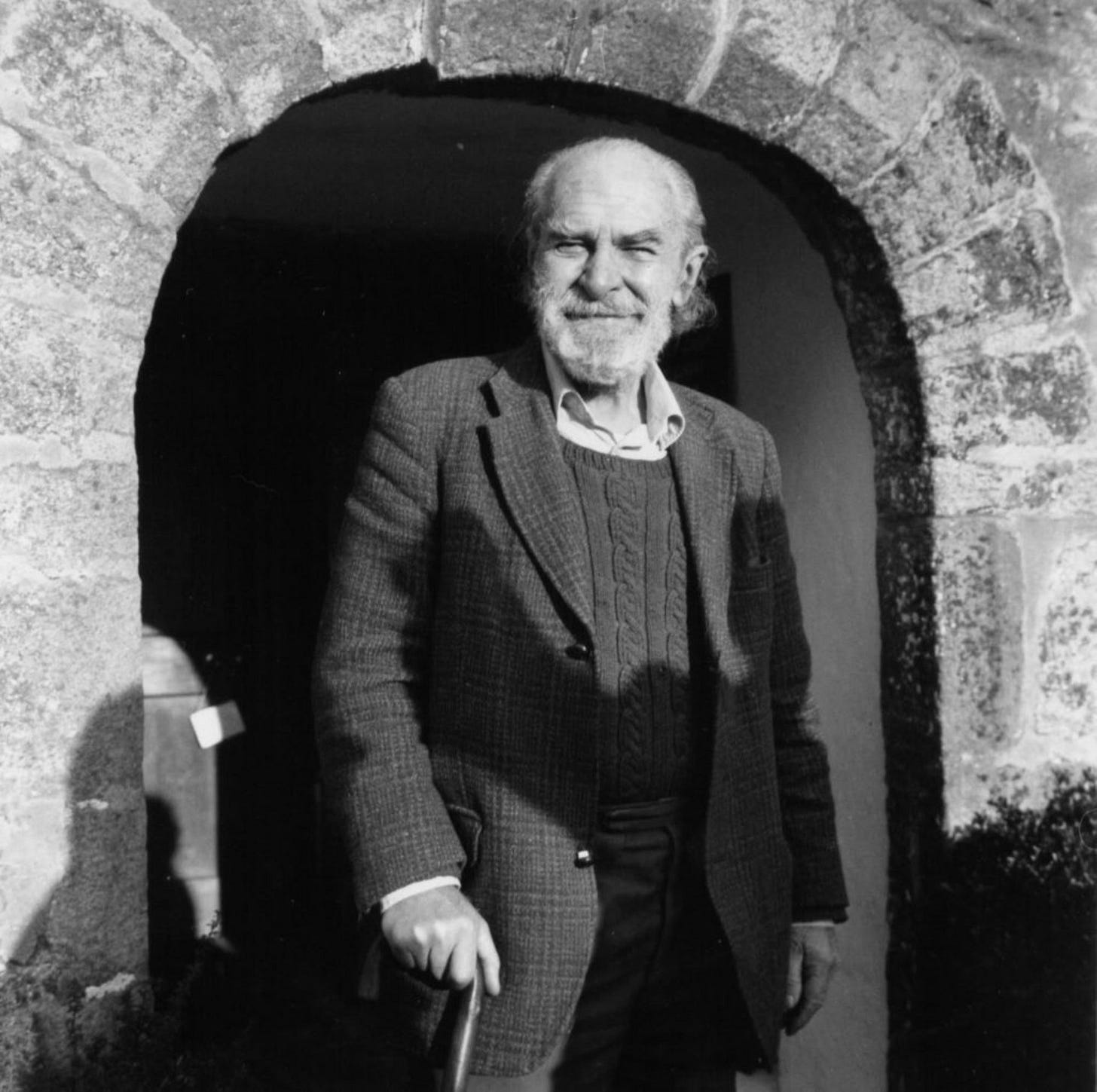

Sean O’Brien reads a poetic masterpiece

It falls way, way short of Paradise Lost and is less than half the length of Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage. Nonetheless, a public reading of Briggflatts, Basil Bunting’s widely acknowledged masterpiece, is not to be undertaken lightly.

Sean O’Brien, another notable poet of the North East (not born here but long resident here), proved himself equal to the challenge posed by its 700 or so carefully calibrated lines.

First the limbering up (assumed rather than witnessed, this not being a sporting arena and Sean very definitely not Noah Lyles).

Then a testing of the microphone, a sip of water to wet the whistle and a few quiet words with harpsichordist John Green who would provide musical interludes between the poem’s five sections, or ‘books’.

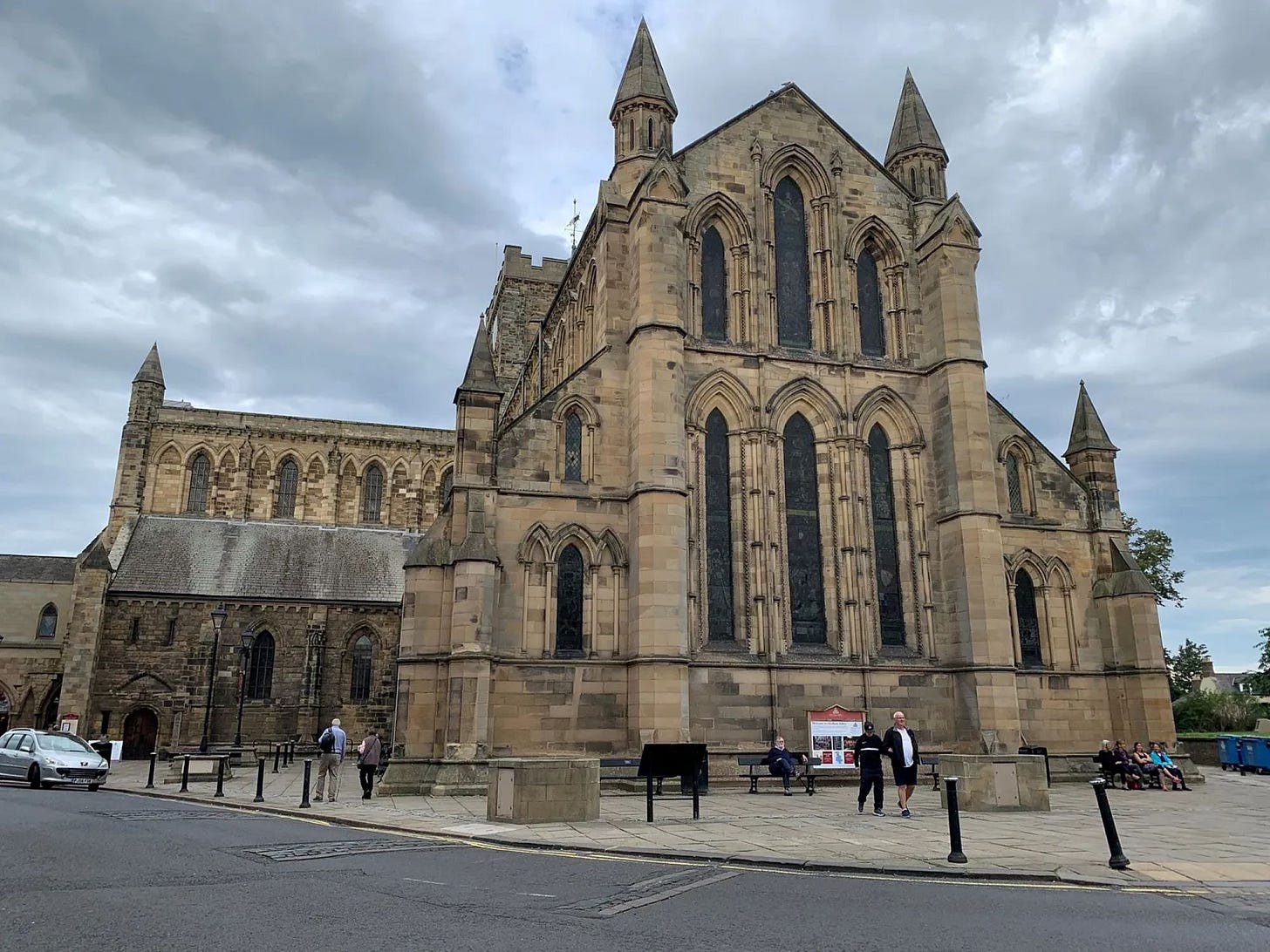

A sizeable, near-capacity audience waited expectantly in the Great Hall at Hexham Abbey for this early highlight of the 2025 Hexham Abbey Festival.

At a glimpse, I have to say, we did not constitute the most youthful of audiences, although spoken word poetry, if judged by the proliferating poetry slam events, does not lack young devotees.

I wondered if anyone gathered in this grand space on a Thursday afternoon had been one of the bright young things present at the Morden Tower, the Medieval monument in Newcastle, when Basil Bunting himself gave the first public reading of Briggflatts on December 22, 1965.

That was 60 years ago. Bunting, born in Scotswood in 1900, died 40 years ago in Hexham, having spent his last years living in the Tyne Valley. Those twin anniversaries made this a doubly special occasion.

But readings of Briggflatts are few and far between, despite its supposed literary importance.

To many, it was “the primary achievement of post-war English poetry”, according to the late Richard Caddel, director of the Basil Bunting Poetry Centre at Durham University, who wrote the introduction to Bunting’s Complete Poems, published by Bloodaxe Books in 2000 as a centenary edition.

The poem, presented as ‘An Autobiography’, was, Caddel added, Bunting’s “celebration of northern home-place and love”.

Moreover, it should be performed.

“Poetry, like music, is to be heard,” Bunting wrote in 1966. It deals in sound – long sounds and short sounds, heavy beats and light beats, the tone relations of vowels, the relations of consonants to one another.”

“Reading in silence,” he added, “is the source of half the misconceptions that have caused the public to distrust poetry.”

As for the ‘meaning’ of poetry, it was akin to the meaning of music.

“Never explain,” Bunting once advised an aspiring poet. “Your reader is as smart as you.”

Speaking personally, I think Bunting might have been a little wide of the mark on this point.

But Sean O’Brien offered the comforting words of TS Eliot, a Bunting fan who arguably knew a thing or two about obfuscation, who once declared: “Poetry can communicate before it is understood.”

“So,” said the man at the microphone before turning to his text, “let’s find out.”

He duly communicated, beginning with the opening lines of Briggflatts in which Bunting nailed his musicality to the mast…

“Brag, sweet tenor bull,

Descant on Rawthey’s madrigal,

Each pebble its part

For the fells’ late spring…”

The language rolled over us, mesmerising and beguiling, and between each section, John Green at the keyboard entertained with the music of the 18th Century Italian composer Domenico Scarlatti which Bunting loved and from which he drew inspiration.

Sean O’Brien has the voice for this kind of thing, deep and sonorous. Not a word was lost, the vocal chords holding up well, and the time flew. The final ‘Coda’ is a beautiful short poem in its own right.

“A strong song tows

Us, long earsick…”

Nobody around me seemed particularly earsick. It had been quite the performance, quite the occasion and well worth the applause.

I never met Basil Bunting, nor heard him speak or read, but I’ve always felt a small personal connection.

At the end of his eventful career – in which he had been imprisoned for his Quaker-instilled conscientious objection in the First World War, travelled widely, rubbed shoulders with Ezra Pound and the bohemian crowd, worked in British Military Intelligence and been a correspondent for The Times – he ended up as a sub-editor, correcting ‘copy’ on The Journal and Evening Chronicle at Thomson House in Newcastle.

It was said that on the train home each night to the Tyne Valley he would work on Briggflatts.

In the archive, there was a photo of him in the newspaper office, sitting in one of the metal-framed chairs which were still in use when I arrived at The Journal, getting on for 20 years after his retirement (they disappeared one day with the typewriters).

At some point, I feel sure, I must have sat in his chair. It’s a small thing but it meant something – and clearly Basil Bunting still means something to a lot of people.

One who had a great deal to do with this event was John Halliday, Basil Bunting’s son-in-law, who wrote the introduction to the programme and was in the Morden Tower on that December day 60 years ago.

His memory of it, he says, “is about the atmosphere generated in that confined space”.

And he adds: “It is tempting to exaggerate but the effect of a dedicated artist voicing his work and being heard by equally dedicated listeners was visceral.

“I cannot pretend to have understood everything that I heard that afternoon but the sense of it permeated then, and remains.”

John remembers his father-in-law’s love of stories, his serious side and his “great sense of humour, dissolving into guffaws at television attempts to dramatize history”.

This occasion, I feel sure, will also be remembered by those who were there.

Hexham Abbey Festival, short and sweet, runs until Sunday. Check the programme here.