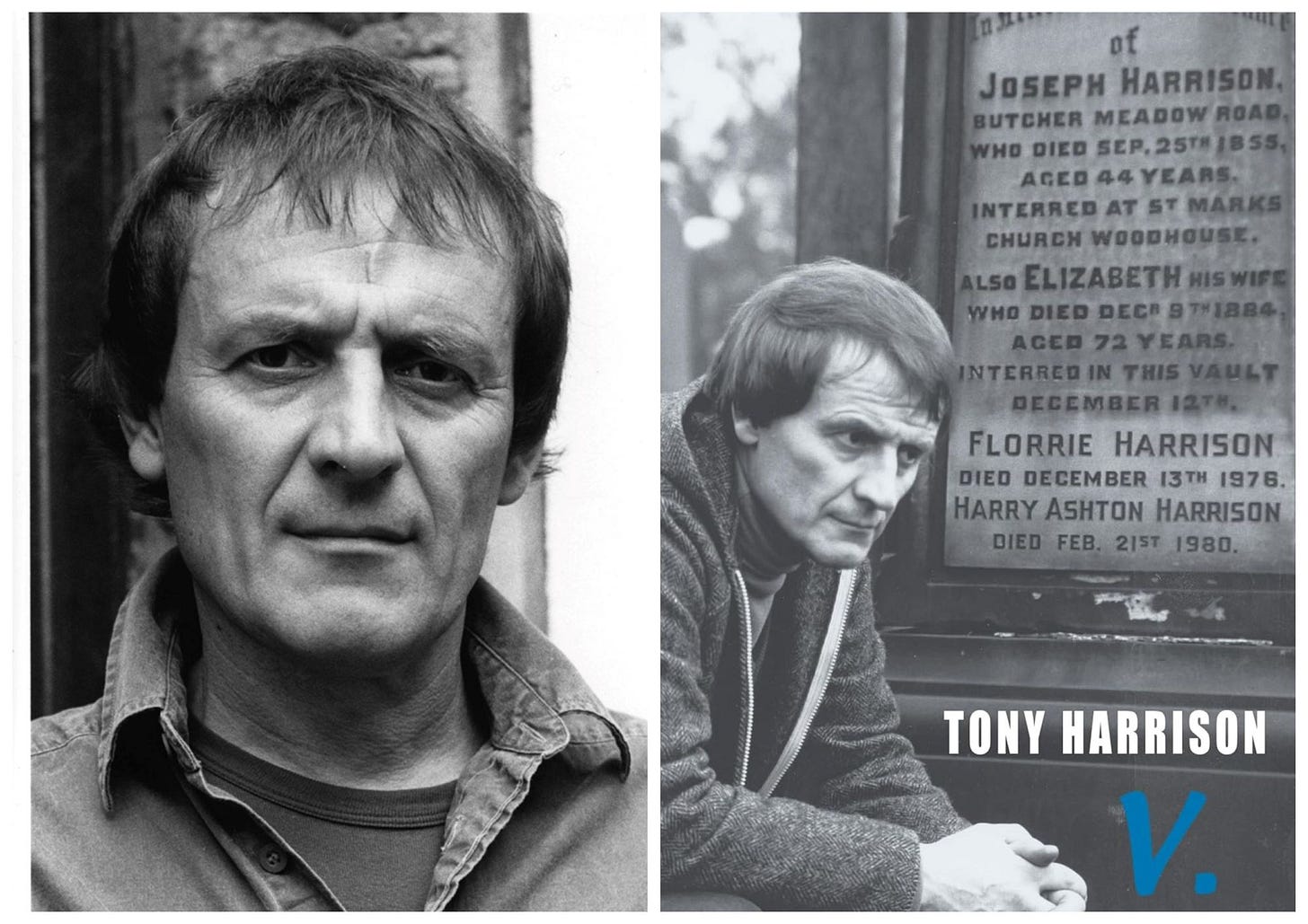

Remembering Tony Harrison, ace poet and journo’s dream

When a poem called V. was headline news

The focus in all the obits and appreciations has been on Tony Harrison the Yorkshire poet. And so he was, born in Leeds in 1937, but although you would never have taken him for a Geordie, he lived for many years in Gosforth, Newcastle.

He died at home on September 26, aged 88.

According to Bloodaxe Books, which published eight Tony Harrison books between 1981 and 1995, he had been suffering from Alzheimer’s disease, which is tragic.

It was a subject he had tackled movingly in one of his powerful TV films, Black Daisies for the Bride, broadcast on BBC 2 in 1993 and winner the following year of the Prix Italia for best documentary.

Many people will have memories of a man who put poetry at the heart of national debate, generated newspaper headlines and could have an audience spellbound with the readings he gave and the plays he wrote for others to perform.

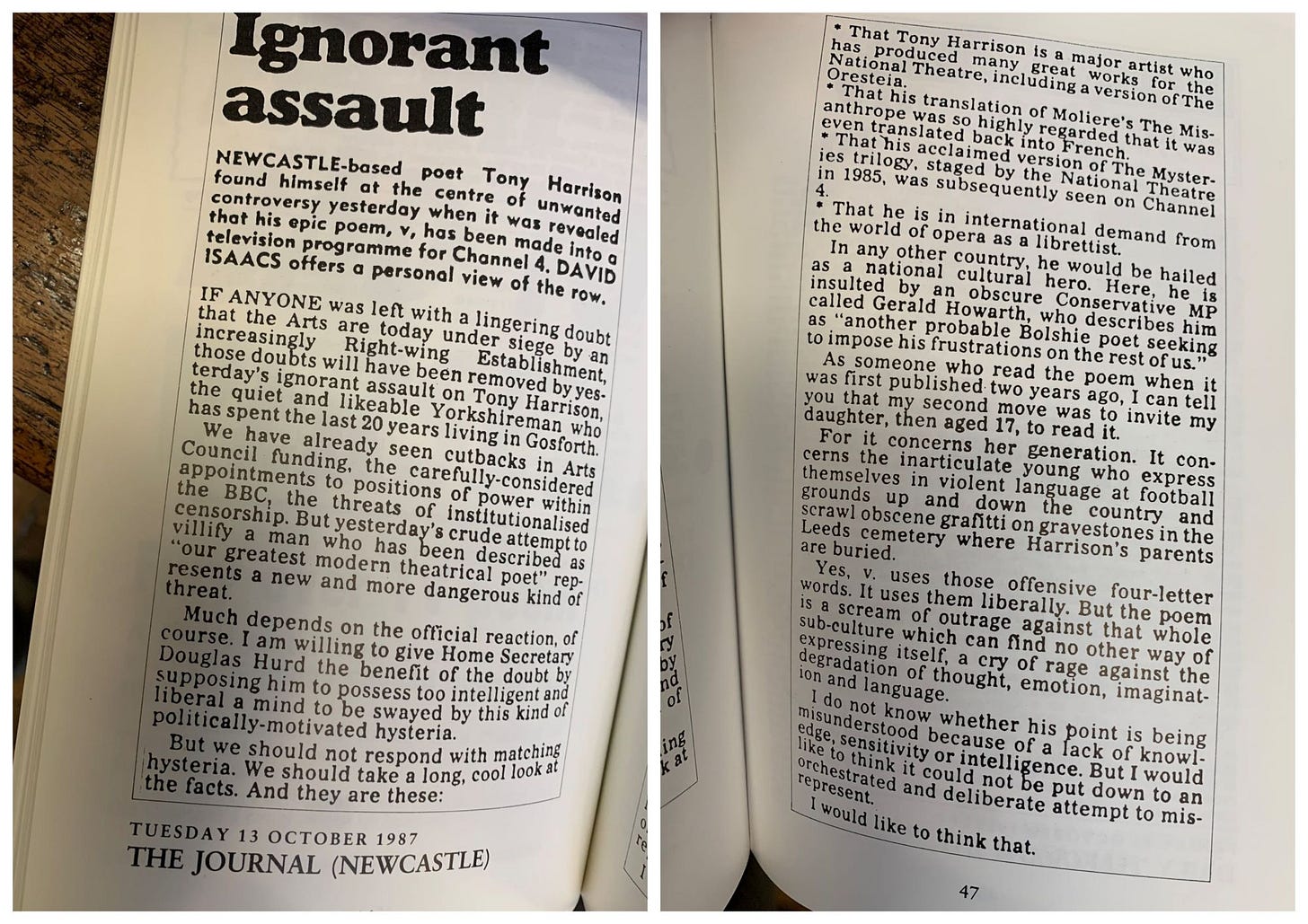

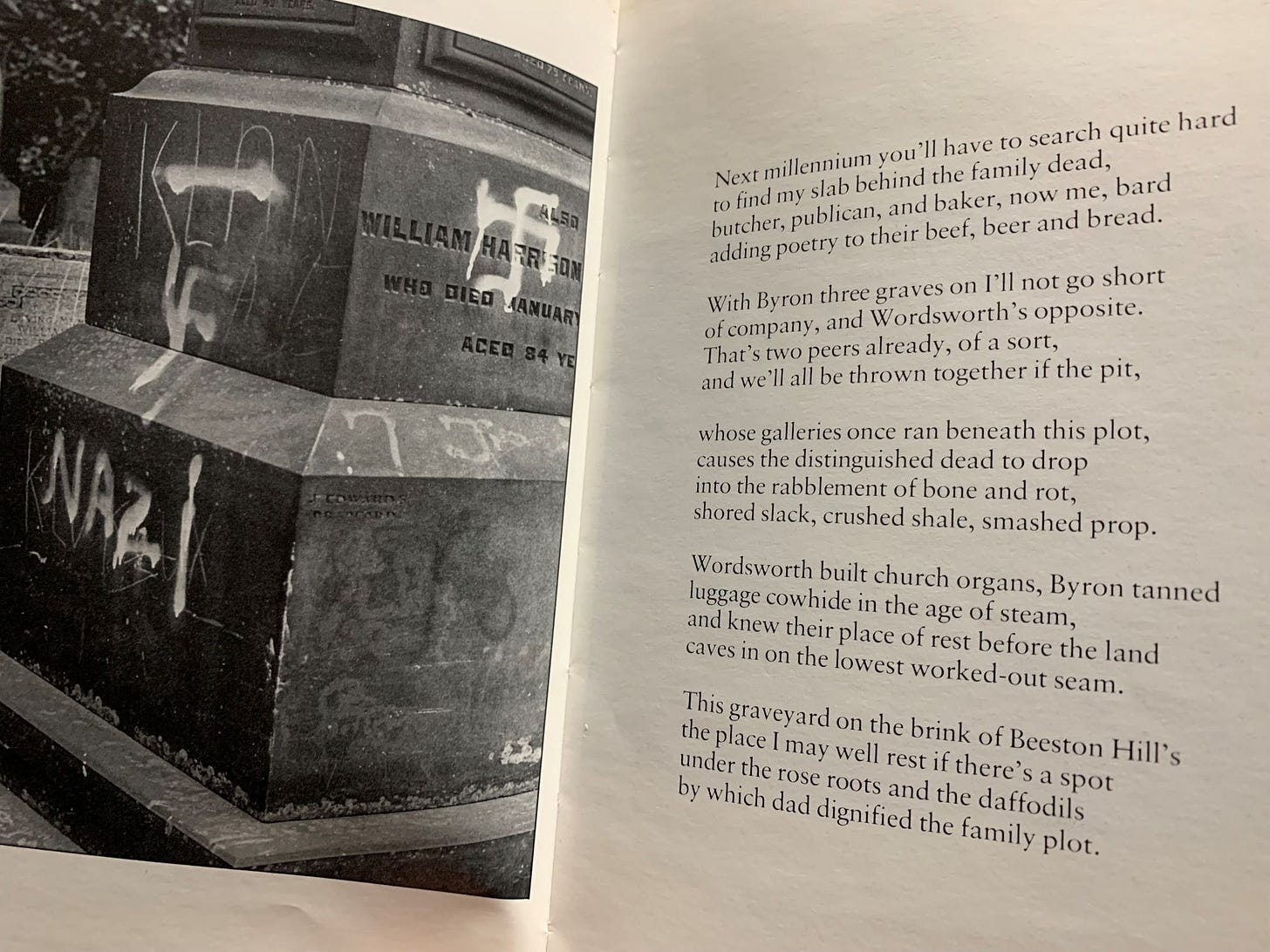

I well remember the fuss whipped up by Channel 4’s decision to broadcast a film version of his poem V. in 1987. The Daily Mail called it “a torrent of four-letter filth” while Mary Whitehouse, self-appointed guardian of public morality, rowed in with “this work of singular nastiness”.

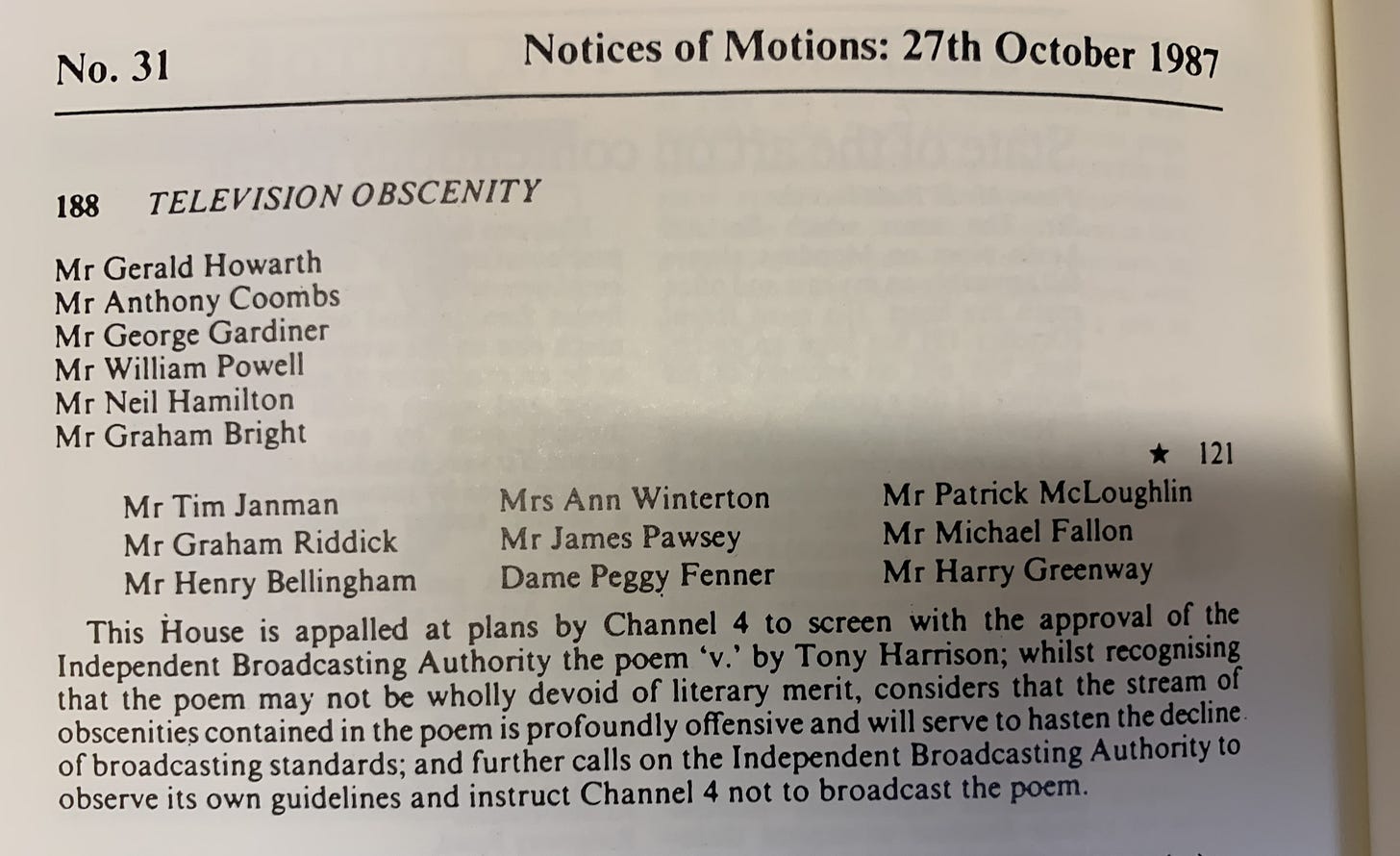

Some MPs, led by the Conservative Gerald Howarth, then the member for Cannock and Burntwood, sought to have the proposed broadcast banned.

Tabloid newspapers in the 1980s, in whose newsrooms ‘four-letter filth’ would have been part of daily discourse, bobbed along merrily on a sea of hypocrisy.

As for Mrs Whitehouse, she almost certainly never read Tony Harrison’s poem which is a reflection on the obscenities he found spray-painted on his parents’ grave in a Leeds cemetery.

It became a political football spinning on an eruption of hot air. In fact, V. is a serious poem, digging for the causes of disaffection and anti-social behaviour in Margaret Thatcher’s increasingly divided Britain.

The newspaper I worked for then, The Journal, published a piece in support of Harrison, putting the frothing fuss in perspective.

Eventually the film was broadcast in an 11pm slot, enabling its writer and narrator to reach a wider and largely appreciative adult audience.

V. won a Royal Television Society Award and Bloodaxe Books, which originally published the poem in 1985, produced another edition with photographs by Graham Sykes and much of the press hoo-ha included at the end.

It makes for a thoroughly entertaining read.

Even the famously sarky Auberon Waugh, writing in The Sunday Telegraph, and after complaining about the “rubbish” written by “modern ‘poets’” and the fact that V. was “too long and repetitive”, couldn’t condemn it.

“People are making fools of themselves who object to the rude words, since they are essential to the scene he is describing and the dialogue which ensues,” he wrote.

Tony Harrison wrote for page, stage and screen but he didn’t make distinctions. All of it was poetry in his view and invariably it was characterised by a compelling rhythmic muscularity.

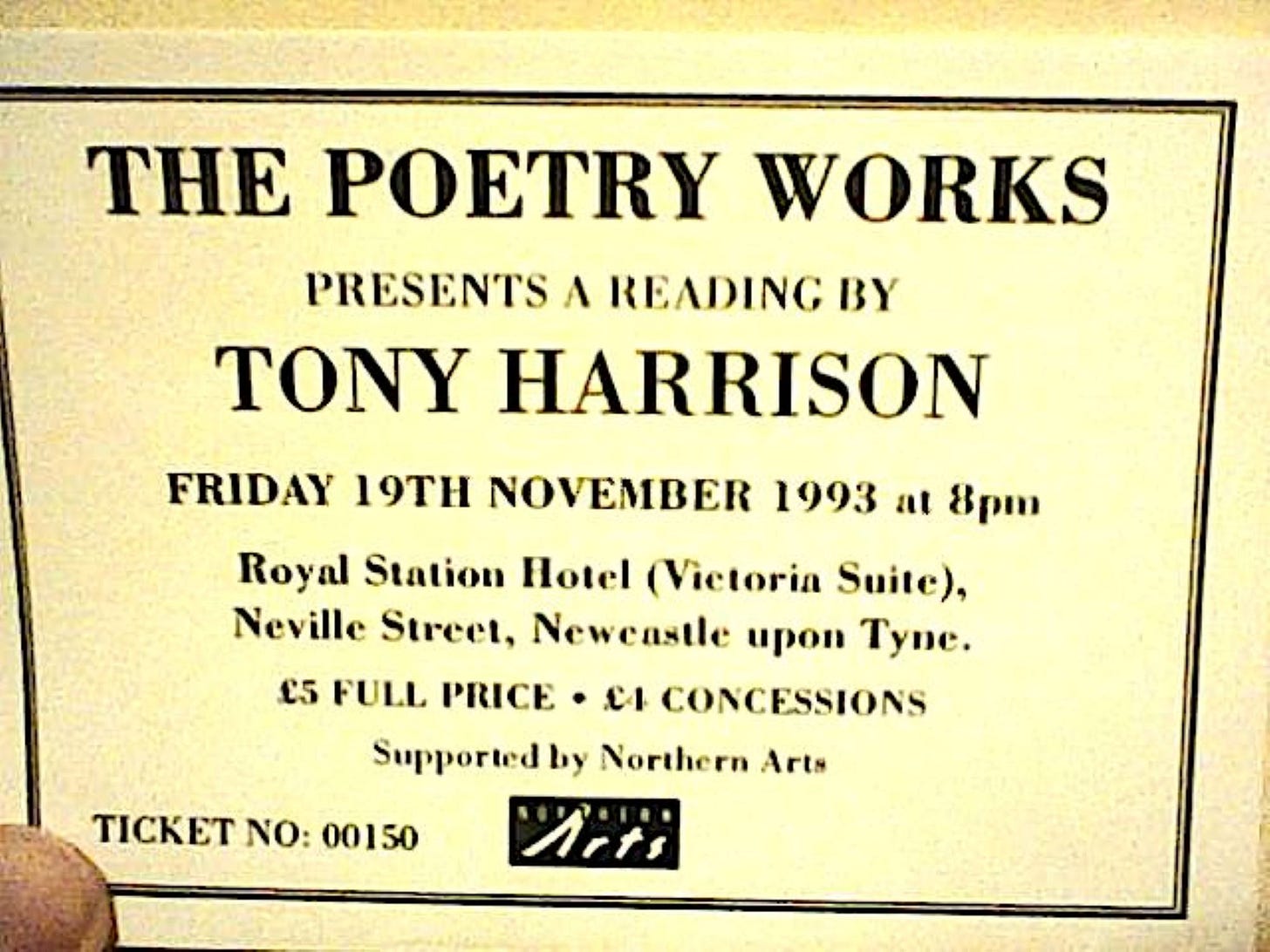

I’m not the only one who remembers a reading he gave at the Royal Station Hotel in Newcastle in 1993 when a large audience sat mesmerised. Tony Harrison was a terrific reader of his own work and it seemed tailor-made for his gruff Yorkshire delivery.

Poetry fan and Cultured North East subscriber Jack Arthurs recalls: “I remember it being the largest attended poetry reading I’d been to in Newcastle (until Seamus Heaney at Newcastle Civic Centre in 2009).

“Tony’s reading was intense and you could hear a pin drop. I snapped up a copy of The Gaze of the Gorgon, his first book-length collection of poems for over a decade, which he kindly scribbled in afterwards.”

Jack also points me in the direction of another Harrison fan, the late Dr Feelgood guitarist Wilko Johnson, who, as plain John Wilkinson, an Essex lad embarking on an English degree at Newcastle University, lodged with the poet.

Wilko, who also played with Ian Dury and the Blockheads, recalled in his memoir, Don’t You Leave Me Here: “The English Department had created a new Poetry Chair and its first occupant was Tony Harrison.

“I wasn’t familiar with Tony’s work and I went to hear him give a reading at the start of term. I was absolutely gripped by what he did. Powerful, metrical and rhymed lines delivered in a grave Yorkshire voice of extraordinary intensity.

“I got to know Tony – he was about thirty then, living with his wife and two children in Gosforth – and I became a kind of disciple. A formidable intellect, a first-class classical scholar, he had read more books than anyone I’d ever encountered. Also a very nice guy.”

They were my impressions of him too on the pair of occasions I interviewed him at his Gosforth home, which, with its books and air of seclusion, seemed a kind of sanctuary, the perfect place to create.

On the first occasion, in the 1990s, he reflected on the first Gulf War when Saddam Hussein’s Iraqi invaders were driven out of Kuwait by US-led coalition forces.

Moved by a chilling photo of a charred Iraqi corpse at the wheel of an armoured car, he gave it voice, reflecting on its own fate and the news that invading American troops had ensured the possibility of posthumous paternity by leaving frozen sperm samples at home.

His poem, A Cold Coming, was published in The Guardian and by Bloodaxe Books in 1991.

Tony Harrison wrote of the present in the context of the distant past.

His acclaimed adaptation of the English Medieval Mystery Plays was staged at the National Theatre in the 1980s, a decade which also saw the premiere of his rip-roaring The Trackers of Oxyrhynchus in the ancient stadium at Delphi, in Greece.

That clever play tickled a lot of people because of its ribald Greek satyrs brought to life by actors sporting huge unwieldy phalluses.

Harrison aimed to blur the lines between ‘high’ and ‘low’ art and accordingly, as well as a run at the National Theatre in 1990, he staged it at a former textile mill in Bradford, calling it belated revenge on a teacher who’d refused to let him recite poetry or take part in plays because of his accent.

Tony Harrison studied classics at Leeds University and then gained a diploma in linguistics. He came to Newcastle in 1967 as the first Northern Arts Literary Fellow, a year-long posting which clearly agreed with him because he settled in the city – and also took up the Northern Arts post a second time in 1976.

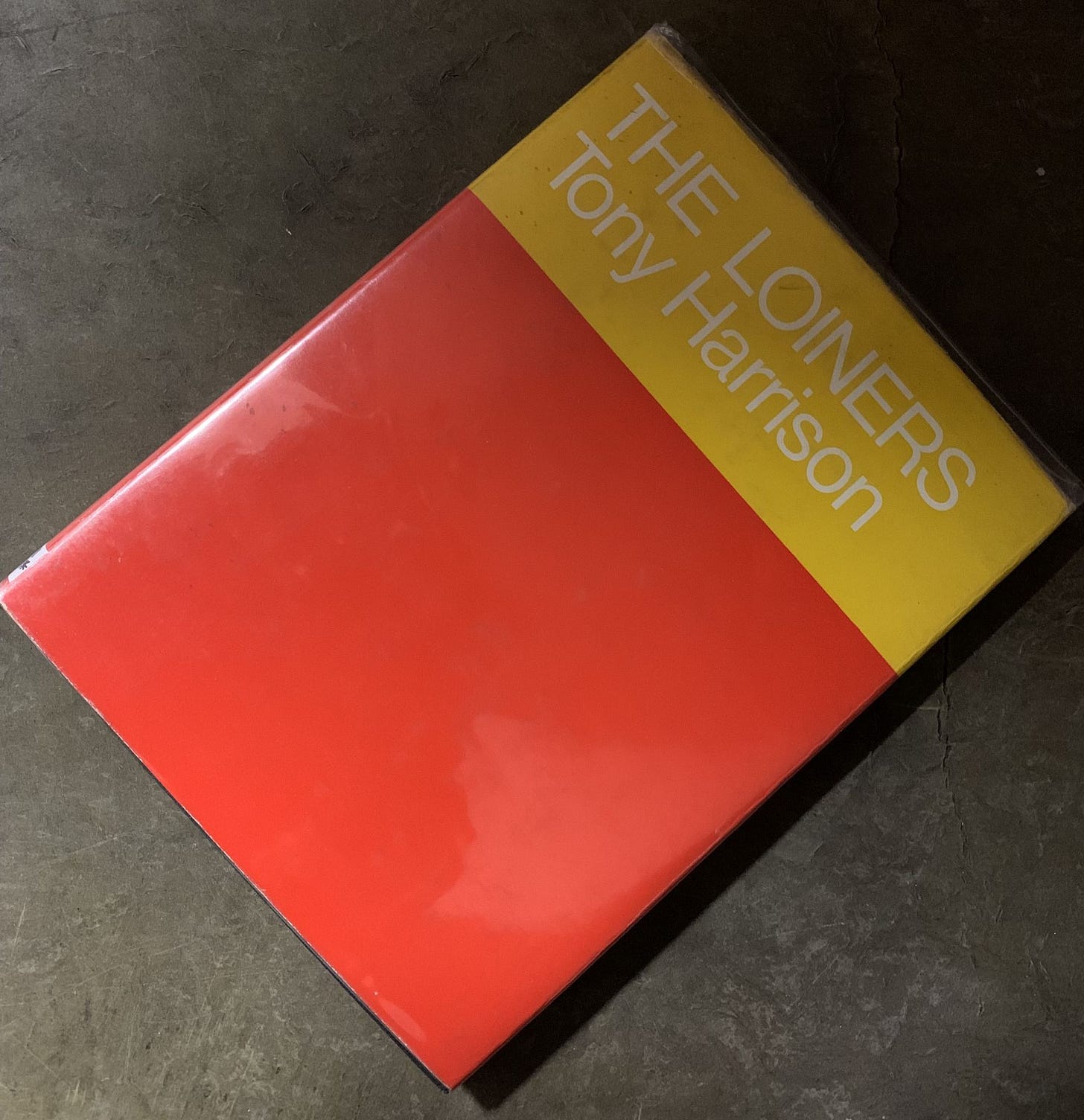

His first collection of poems, The Loiners, including some poems he wrote as Northern Arts Literary Fellow, was published in 1970 and won the Geoffrey Faber Memorial Prize.

I interviewed him again when he was announced as the third winner of the Northern Rock Foundation Writer’s Award (worth £60,000 over three years) in 2004.

We talked, I remember, about Prometheus, his film-poem of 1998, inspired by Greek myth and Shelley’s 1820 ‘lyrical drama’ Prometheus Unbound but given contemporary relevance, starting with an elderly miner reflecting on the past in a blighted post-industrial landscape.

Intended as a comment on the fall of the working classes, Tony Harrison was credited this time as director as well as writer.

Leading scholar Prof Edith Hall, of Durham University, editor of a book called New Light on Tony Harrison (Oxford University Press, 2019), called it his “most brilliant artwork”, with the possible exception of The Trackers of Oxyrhynchus.

A series of events marking the 40th anniversary of the publication of V. is taking place during October at various literary festivals.

At Durham Book Festival (October 10 to 12), an event called Rewriting V. will see three poets – Malika Booker, Paul Farley and Darlington-born Jo Clement, whose debut collection, Outlandish, was published by Bloodaxe in 2022 – re-imagining the famous work.

The event, at 2.30pm on Saturday, October 11 at Gala Durham (but also to be live-streamed), will be chaired by poet Andrew McMillan.