Remembering the savage winters of Northumberland’s past

Valley author recalls the days when snow in winter could be a life or death affair. He talks to Tony Henderson

The blizzard of headlines about the first snow of the winter would have perplexed past generations who lived in a Northumberland valley.

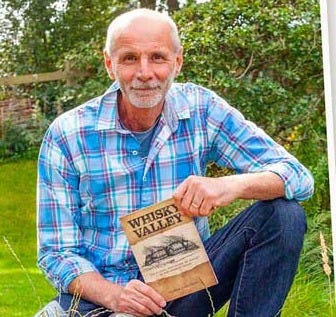

The reaction certainly bemuses author Andrew Charleton, born and bred in the Coquet Valley and who lives in Rothbury.

He has written his latest book on the sort of snow which could cut off people in upland locations for months.

“Imagine living then when the winter weather could be savage. If you think that the winter weather today is bad you should have lived when it was much worse in days past,” says Andrew, retired after a career in the water industry and who has written books on the illicit whisky stills in Upper Coquetdale and also the area’s folk tales.

“What is truly amazing is the stoicism of the hill farmers. Today society grinds to a halt amid hand wringing when half an inch of snow falls on the road out of Rothbury.”

Andrew was helped in compiling his book Lost to the Snow by dipping into the 19th century diary of his great grandfather Richard. The weather played a prominent part in his life as a farm manager and agricultural valuer based in the valley at Snitter, near Thropton.

Andrew had his own recent experience to draw on when in December 2023, on a clear blue sky day, he and his wife Celia drove to Coquet Head to take pictures.

They travelled through Alwinton in sunshine but just past Blindburn the sky began to darken.

“The atmosphere of the valley changed completely. Up ahead the road was turning white with snow and visibility shortened to around 20 yards,” says Andrew, who turned to retreat to Rothbury.

“The journey back was very precarious indeed, with snow falling so quickly that the entire valley was unrecognisable. I drove at around five miles an hour for what seemed an eternity.”

For Andrew, it was a sharp reminder of Coquetdale winters past. “The winters of 1947 and 1962-63 are regarded as the worst in living memory. But these extreme weather events were by no means unique. Remote communities endured winter privations for centuries.”

Andrew tells the tale of Jean Foreman (née Telfer), who was born in 1943 at Usway Ford Farm in the upper valley. In 1947 Jean and her family and six shepherds were cut off for 14 weeks.

“The hardship endured by farming communities can only be imagined today. Fourteen weeks at the mercy of driving snow and freezing temperatures with no prospect of outside assistance as flocks perished would test endurance to its absolute limit,” says Andrew.

In 1955 weeks of severe weather left the farm in isolation again. As the feed store for the sheep was becoming desperately low, Jean’s father walked the perilous miles through drifting snow to the only telephone in the valley at Barrow Burn.

The family was told hay bales would be dropped from an aircraft and were asked to mark the spot with a nine-foot-wide letter C in the snowy landscape.

This they managed by digging into the frozen farm midden to reach the black layers below and carry it by sledges and buckets to the blanketed drop zone.

“The hardy souls of the valley waited until they were absolutely desperate before they thought of seeking help,” says Andrew.

Avalanches, or snow slips as they were known locally, were a real danger in Upper Coquetdale, often resulting in loss of livestock and in one case a human life.

“In some parts the valley sides are so steep that a large accumulation of drifted snow would cling precariously to the higher levels and as fresh snow blew over the top, huge overhangs would build up until their own weight would set them off down the hill at terrifying speed,” says Andrew.

Between Blindburn and Carlcroft what was recorded as a “perfect avalanche” obliterated the channel of the River Coquet and filled the bottom of the valley to a depth of 50ft.

The Rothbury parish register for 1819 records how shepherd Thomas Turnbull, 42, from Milkhope died after being “overwhelmed” by 18ft of snow, with his body not recovered for several weeks.

“It was not unheard of for farms to be cut off for three months or more. Self sufficiency, self reliance and incredible personal resilience would have been as valuable as fuel, candles and food,” says Andrew.

The Newcastle Journal reported how in the winter of 1886 a shepherd called Rogerson was found dead in a shop stell – a drystone shelter – while another shepherd, Henry Hall, died in a heavy snowstorm.

The tragedy of Hall’s death is believed to be the subject of the painting Faithful Unto Death by Cullercoats artist Henry Hetherington Emmerson, a friend of Lord Armstrong, and which is displayed at the inventor and industrialist’s Cragside home.

On December 3, 1863 Eleanor Herron, known as Nellie, had been providing medical help to a shepherd in Alnham village.

She set off in a severe snowstorm on the five-mile walk back to her home at Hartside in the Ingram valley. She never reached her destination.

A stone memorial, known as the shepherd’s cairn, recalls the deaths in 1962 of Jock Scott and Willie Middlemas, who died in heavy snow as they returned from Rothbury Auction Mart to their home in Ewartly Shank, three miles from Alnham.

Lost to the Snow, by Andrew Charleton. Coquet Books, £9.99.