Remembering Paul Collard, visual arts champion and 'visionary'

Funeral attracts big Hexham Abbey turnout

There was a large turnout at Hexham Abbey on Wednesday for the funeral of Paul Collard whose recent untimely death at the age of 71 shocked and saddened a lot of people.

The service was conducted by the Rev’d Canon David Glover and it featured moving eulogies by Paul’s son, Ben, and daughter, Bryony, and also by his brother, Ron, six years his senior.

They spoke of a man who, though taken too soon, had led a fulfilling and adventurous life, a diplomat’s son whose early years were spent in various different countries until he was sent to boarding school in Britain.

From Ampleforth College, in North Yorkshire, he went to Cambridge University where he met his wife, Hilary, and thereafter gravitated towards a career in the arts, becoming convinced of the transformative effect they could have on people’s lives.

Peter Hewitt, who was chief executive of Northern Arts (1992-97) and then of Arts Council England (1998-2008), recalled Paul’s sharp intellect and terrific work ethic - and also his persuasive powers and ability to get on with people.

Given the job of running the then failing Institute of Contemporary Arts in London at the age of 28, and with almost no relevant experience, he had made a great success of it and turned it round.

In more recent years he had worked all over the world and a song written about him by students he had encountered in Thailand was played at the funeral. Clearly he had won their deep admiration and affection.

We learned of a man who was a loving husband, a devoted father and a keen cook and gardener, someone who would always take care to deflect praise for what he did onto others and acknowledge the efforts of those outside the spotlight.

Many people who didn’t know Paul personally benefited from the work he did as a champion of creativity in education.

He succeeded Peter Jenkinson as the national director of Creative Partnerships which was set up by the Labour government in 2002 to develop young people’s creativity by bringing artists and schools together.

Funded principally by the Department for Culture, Media and Sport, it was managed first by Arts Council England and then by Creativity, Culture and Education (CCE), the international foundation set up by Paul and based in Newcastle.

Funding for Creative Partnerships was cut by the incoming Coalition government but CCE went on to work across the world, initiating and collaborating on creative education projects.

In 2011 it won an award from the WISE (World Innovation Summit for Education) Foundation for the Creative Partnerships programme which had reached more than a million children across England, helping to develop skills and raise aspirations.

But Paul first came to the North East in 1993 to head Visual Arts UK and put together a year-long programme in 1996 that would make the region a national showcase for the visual arts.

It was one in a series of year-long art form celebrations devised by the Arts Council to mark the coming new millennium.

Cities or regions had to bid for the honour of hosting one of them and did so, drawn by the benefits it might bring in terms of profile and tourism.

The North East and Cumbria – then the area run by Northern Arts, the regional arts body that eventually was absorbed into Arts Council England – bid for the Year of the Visual Arts.

It was an audacious bid. The region was large, encompassing great rural expanses as well as urban centres, and not lavishly blessed with art galleries (this was pre-Baltic, pre-Mima, even pre-Biscuit Factory).

But the bid team’s pitch, led by Northern Arts (initially Peter Stark and then his successor, Peter Hewitt) was that the whole region would become a gallery.

Glasgow, fresh from its 1990 European City of Culture success, was the hot favourite, I recall. But the North East bid won and Champagne (I believe this was pre-Prosecco) flowed at a celebratory bash at Newcastle’s Guildhall in 1992.

After the fizz came the job of making it actually happen… and Paul was hired to run the enabling company that had been named Northern Sights.

With his experience at the Institute of Contemporary Arts, and also a spell at the British Film Institute, behind him, he burst onto the scene determined to blow away what he saw as the national media’s “terrible cynicism” towards the region.

He characterised the London-centric attitude as: “Why the North of England? What have they ever done in the visual arts?”

He set about confounding many people’s expectations, preferring to involve local people in making the 1996 year of the visual arts a success rather than importing a proven curator with a familiar name to oversee the programme.

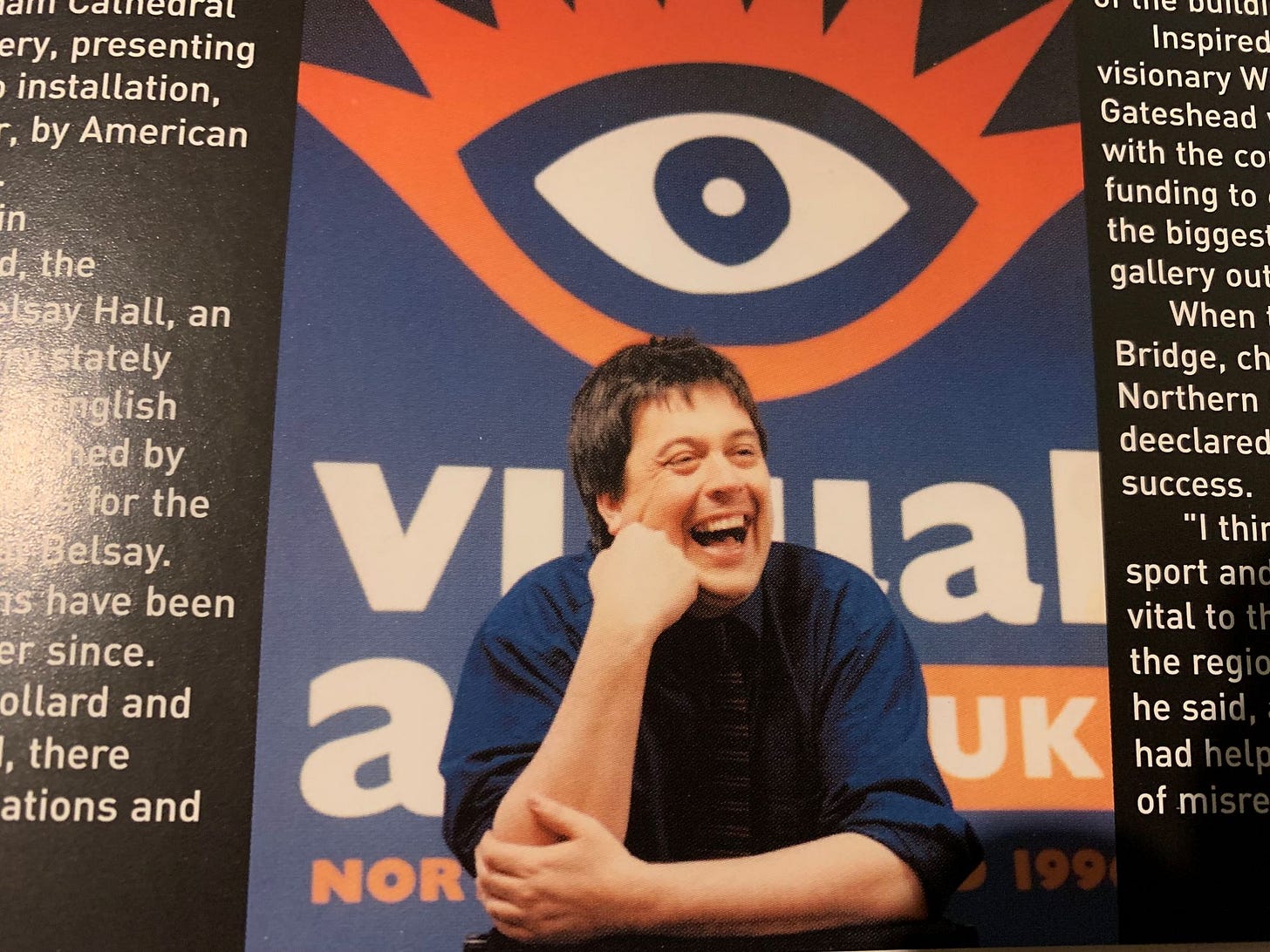

Then a youthful 41, he was a bundle of energy and ideas, inspirational, irrepressible and with a ready laugh that frequently gave way to giggles.

He was fun to be around, never short of a good story for a journalist and wired to bring out the best in people.

The photo of him laughing in front of the eye logo of Visual Arts UK is how I best remember him.

And that logo became something of an icon. A version of it was forged in metal beneath Grey’s Monument in Newcastle (by a French performance group called Katertone) to begin the year-long programme.

Andrew Dixon, now living in Edinburgh, was number two to Peter Hewitt in 1996 (later rising to the top job before heading NewcastleGateshead Initiative and later becoming an adviser on major cultural projects). He said of Visual Arts UK before the funeral: “It was incredibly important in the chronology of what’s happened. You can trace a lot of things back to that bid.

“Paul took the ambition to another level. He was determined that everyone should have their work in the spotlight, so every local authority area, about 32 of them at the time, would have a dedicated week during the year.

“His advocacy helped to pave the way for The Angel of the North and many other things that happened subsequently.

“The moment for me that summed up Paul’s genius was when he projected 96 images from Visual Arts UK onto the wall of the Baltic Flour Mills building in Gateshead before it was developed.

“It was Paul signalling that this was what we’ve done but this is what we want to go on and do in the future.”

I clearly remember Paul explaining his twin ambitions for 1996: that it would change perceptions of the visual arts within the region while also changing the outside world’s perception of the region.

I would say both ambitions were achieved. Media cynicism towards the visual arts was rife locally as well as nationally, with newspaper headlines mostly either inviting ridicule or questioning cost.

Paul Collard’s running of Visual Arts UK saw an initial £250,000 from the Arts Council generate £10m in work created, with sponsorship provided by major North East companies.

The year sits in a clear timeline between the Northern Arts Case for Capital campaign of 1995, calling for major investment in the region’s arts infrastructure, the erection of The Angel of the North in 1998, Gateshead Millennium Bridge opening in 2000 and Baltic opening in 2002.

One of the most popular attractions of 1996 was Antony Gormley’s Field for the British Isles. Displayed in a big shed in Gateshead, its thousands of tiny terracotta figures introduced the public to the man who had been commissioned to create that landmark sculpture.

But there was so much else in what was later seen by many as the most successful of the celebration years.

The Lindisfarne Gospels was displayed at the Laing Art Gallery, Durham Cathedral hosted The Messenger, a wonderful (and mildly controversial) video installation by American artist Bill Viola, and Belsay Hall invited artists to respond to the building for a hugely popular exhibition called Living at Belsay.

In Newcastle, 53 banners designed by North East artists were flown from the flag poles of city buildings.

They’re long gone but surely they would have been flying at half-mast on Wednesday in commemoration of a man who achieved some great things.

Paul loved the North East, settling in rural Northumberland with his family. And he continued to make waves. The YouTube video you see here shows him receiving a Changemaker Award last year from Curious Minds, a national charity based in Wigan, in recognition of his life’s work.

A tribute posted on the Curious Minds website after news of his death states: “Because of Paul, in England alone more than a million children and young people had a creative education.

“He was a visionary, working at the forefront of creative and cultural education to influence both policy and practice.”

Thank you for such a beautiful written celebration. Captures the fun and focus of a person who inspired so many creative ideas to become reality and touch many lives. Recently recalled documentary screening over the Tyne onto empty Baltic (audience in Quayside redevelopment rubble, soundtrack on Radio Newcastle). Field in disused Gateshead shed transfixed visitors (including our two under-10s). Your report will have brought back special memories for many readers.