New book spotlights half a century of digging at Vindolanda

After 50 years of digs it’s 50 of the best finds from a treasure trove of a Roman fort. Tony Henderson reports

By the end of the month (September), the latest in a 50-year series of annual digs at a Northumberland Roman fort will finish and add to the tens of thousands of finds from the site.

The current Vindolanda database holds 40,476 objects, but that figure doesn’t include the fort’s famous writing tablets, pottery, animal bone and textiles, which have survived in the exceptional preservation conditions at the fort.

A succession of timber and stone buildings and structures were layered across the site during its 300 years of occupation, effectively sealing the remains and preventing them from vanishing through decay and disturbance.

These include around 7,000 shoes, and the leather and wood collection at Vindolanda is among the best in the Roman Empire.

The excavations at Vindolanda have revealed some of the most precious and unique artefacts in Roman history.

From leather boxing gloves and children’s shoes to wooden hair combs and the first evidence of female handwriting in Britain, the collection typifies the amazing and diverse array of material culture present in Britain during the Roman period.

The objects demonstrate the connections of Britain to the Continent and the Mediterranean world of the Roman Empire.

Dr Andrew Birley, chief executive of the Vindolanda Trust, cites the writing tablets – “the thin ink on wood letters. It is astounding that they should be preserved for us to recover and read today”.

The archaeologists and hundreds of volunteers who snap up digging places as soon as they are offered at the start of each year have, says Andrew, “reshaped our appreciation of what it meant to be a Roman soldier serving in Britain.

“Because of some of the extraordinary finds from the site we have a much clearer idea who one might have met in a Roman fort or military town nearly 2,000 years ago.”

Spoilt for choice does not cover the scale of the task undertaken by the Trust’s curator Barbara Birley and researcher Professor Elizabeth Greene when they set out to select their favourite 50 finds.

They have been decanted into a book, 50 Objects From Vindolanda, from Amberley at £15.

Andrew says: “Each was held, created, traded, written, loved or lost by a human hand and by marvelling at and enjoying these things today we better appreciate the people to whom they once belonged.”

Barbara says of the chosen 50: “Each object is special for some reason. I think what made them stand out is both their preservation and in many cases their connection to the everyday at Vindolanda.

“Many of these objects would not look out of place in our own lives, be they shoes, combs, tools or jewellery, and this links us directly to our past. There are some finds like swords and armour which seem foreign to us but still fascinate us.

“Many stand out just because they are ordinary, but this makes them extraordinary when they come together to tell the stories of the people who lived here nearly 2,000 years ago.”

The population at Vindolanda would have made best use of what could be found in the terrain around the fort. An example is juniper haircap moss, which grows in the high woody areas around the fort.

The moss was used to create one of the 50 items – thought to be a crest for a helmet.

A total of 2,240 strands of the moss were folded and stitched to give the impression of horsehair.

Another type of moss was also used to create a wig, with stems knotted into a cone and plaited to form a cap. Loose strands were left to fall from the cap for 20–35cm on the sides and back, and 7–10cm at the front like a fringe.

Part of the goods entering Vindolanda would have had a long journey by sea and horse and cart to the northern frontier, such as the ruby red and higher-class Samian pottery, produced in Gaul (modern France).

A consignment, with items still stacked together, was discovered discarded in a ditch at the fort, when they were found to have been damaged in transit. The ditch also contained the contents of a barrel of oysters, probably spoiled during their journey. One can imagine the disappointment, frustration and curses.

Some objects are evidence of women and children at Vindolanda. One of the finest leather shoes in the collection is a leather sandal belonging to Sulpicia Lepidina, the wife of the fort commander Flavius Cerialis, and found in their quarters along with a baby boot and shoes of children and adolescents.

The sandal is incredibly fine and detailed, and includes stamped floral motifs and the name of its maker, Lucius Aebutius Thales, making this one of the first designer labels in history.

The most elaborate earring found at Vindolanda is a gold circle surrounding a green glass bead made to look like an emerald.

A silver brooch is in the form of a stylised duck. A silver ring is inscribed with the words Matri/Patri, which translates as mother/father, perhaps serving as a sentimental reminder of the owner’s original home.

A gemstone is set into another gold ring, with the words anima mea, taken to mean “my soul” or “my darling.”

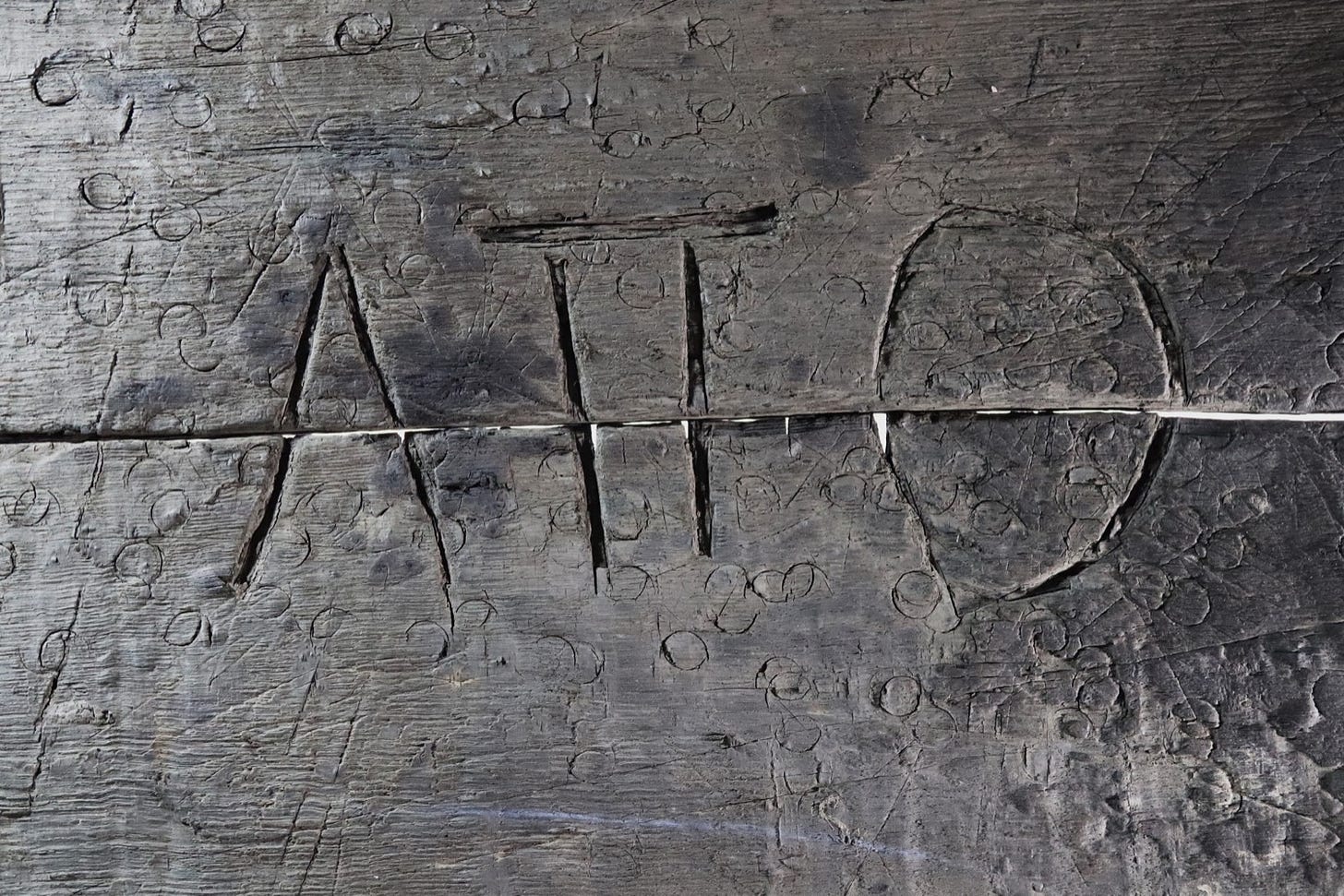

A plank from a workbench provides a direct link to its owner, who carved his name Atto into the wood.

The cemeteries outside the fort have not yet been located but one tombstone, reused in a later building, is to Titus Annius of the First Cohort of Tungrians, from what is now Belgium.

What survives of its inscription is that he was a centurion, he had a son, and that he died in bello – in the war.

Life was not all boxing matches and oysters at Vindolanda.