My Austen sequel and a tiger who came to dinner

The adventures of Lydia and Irene

What better time to publish a sequel to Pride and Prejudice than during this anniversary year with Jane Austen fans worldwide marking 250 years since the author’s birth?

The timing, explains Irene Waters, owes more to luck than planning. Had it not been for Covid, her Letters from Lydia might have pre-dated the anniversary.

But the book’s out now, described on the back as “a fascinating sequel to Lydia’s story”, merging fiction with fact and “perfect for Austen fans and readers who enjoy historical fiction”.

Liberally illustrated, it juxtaposes Lydia’s imagined letters home with author’s notes giving context to her references to trips, new acquaintances and society balls in 18th Century Newcastle.

It’s to that city that the youngest, triumphantly first married and arguably silliest of the five Bennet sisters heads at the end of Pride and Prejudice.

Her new husband, charming but caddish Lieutenant George Wickham, has been posted there with his regiment, you see.

What happens when they get there?

Jane Austen doesn’t say… which is where Irene steps in with this epistolary account of two hectic years in the North East, rubbing shoulders with Collingwoods, White-Ridleys and even Thomas Bewick.

“Now most people think of being sent to Newcastle as being sort of banished to the uttermost part of the earth,” Irene tells me at her home in Bedlington, Northumberland.

“But I’d done some work for the Avison Society (keeping alive the legacy of Newcastle-born composer Charles Avison) and I realised that actually there was quite a lot going on in Newcastle in the 18th Century.”

“Banished to the North” is the phrase attributed in the Austen novel to highly strung Mrs Bennet, desperate to see her girls wed.

Irene has been on the case for over a decade, since she signed up for a week-long course called Jane Austen Dances, organised by the Historical Dance Society in Chichester.

“A week or so before, they notified us that we were expected to contribute to a Jane Austen at Home evening,” she recalls.

“They suggested various things we could do and I thought: I can’t do any of those. There’s no historical dance group up here so I couldn’t do anything in the way of dancing.

“Then I remembered that in Pride and Prejudice Lydia had been sent to Newcastle, so on the way down on the train I made up a letter from Lydia, writing home after she’d arrived.”

She read it aloud and it went down so well that the Historical Dance Society published it in their quarterly newsletter. Then they asked Irene if she had any more.

With a smile, she says she found out later that much of what she’d put in that first letter was wide of the mark.

“There were facts in it but a lot of it I was just making up. But one thing led to another.

“I got engrossed in the newspapers of the time. The Newcastle Courant was published right through the 18th Century and the City Library had the whole lot on microfiche.

“I spent hours on the top floor reading though all these newspapers and they were absolutely fascinating.”

Based on her research, Irene gave a couple of talks at Historical Dance Society functions, and it occurred to her one day that maybe there was a book in it.

Unable to interest a publisher, she decided to self-publish through Troubador which is based in Leicestershire where she grew up. All was going to plan until the pandemic closed the library.

Undaunted, Irene set about ordering second-hand books online, extending the scope of her 18th Century research and swelling her manuscript.

Looking back at people’s commendable concern for her during lockdown, she giggles.

“People thought I was lonely and miserable. I wasn’t actually because I had Lydia for company. She was fun.”

Whatever the course of the Wickhams’ marriage – Irene suspects they would have been flirting outrageously soon after exchanging vows – Lydia bubbles out of the fictional letters.

But when she enthuses about attending a Christmas party at Mr Brandling’s house in Gosforth, the following notes explain that Charles John Brandling was MP for Newcastle from 1784-98 and a hospitable and generous chap.

Lydia skates on the frozen Tyne (in accordance with a Courant report of 1795) and sees an elephant in the Bigg Market (as the newspaper reported at about the same time).

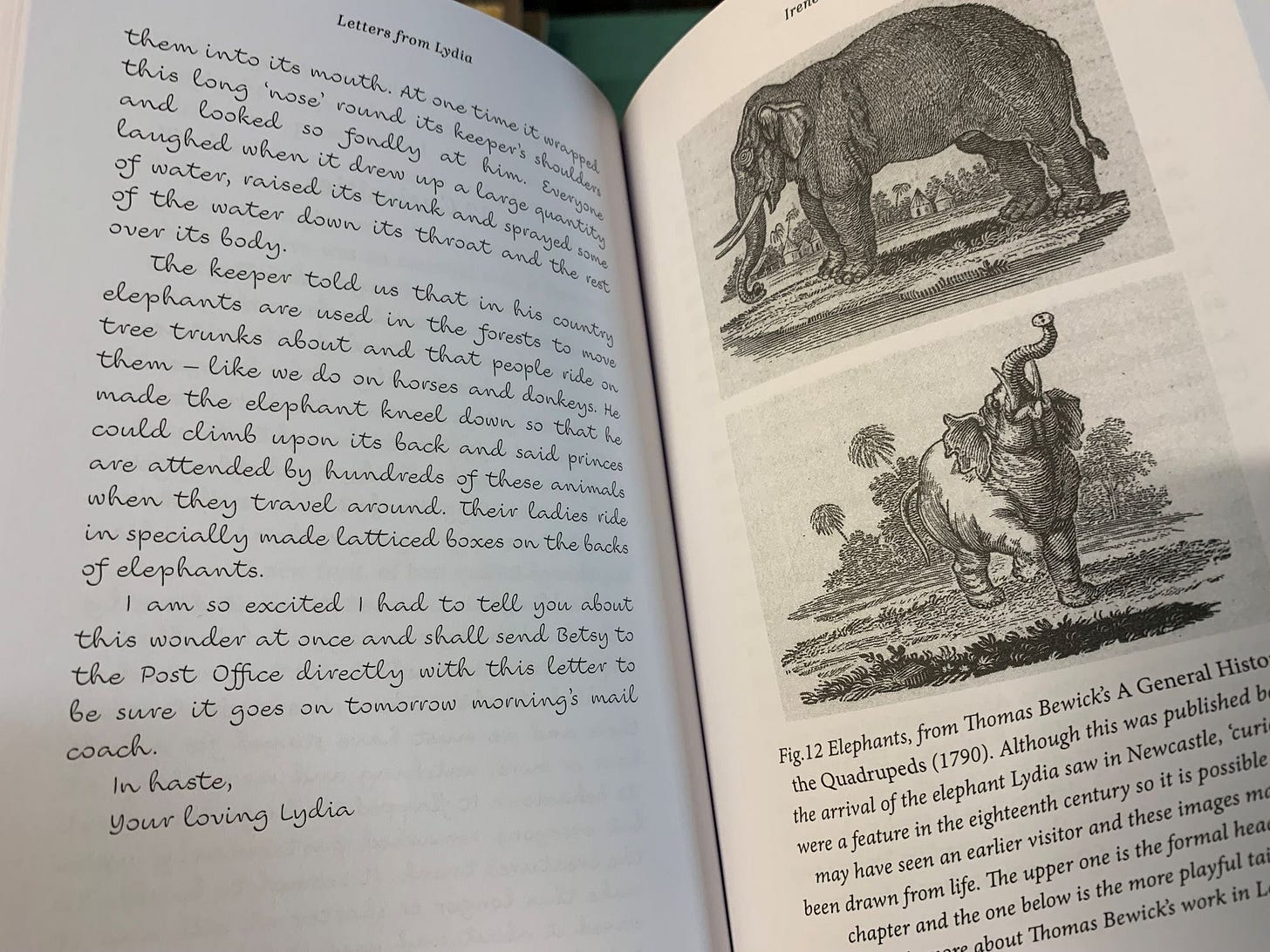

Irene’s notes feature almost contemporaneous elephant engravings by Bewick.

After Lydia has told “my dear ones” of her cook’s method of pickling salmon “the Newcastle way”, the recipe, taken from Mary Smith’s recipe book of 1772, the year she left the service of Sir Walter Blackett, is included in the notes.

Irene recently turned 95 and is well qualified to say that, as a writer, she is “not a novice”.

She tells me of her career in education, rising to be head of geography at a girls’ school in Buckinghamshire before coming to the North East in 1968 to work in teacher training.

She ended up at Newcastle Polytechnic, writing the syllabus for a course called The Arts in Society and Community and then a correspondence course followed by a textbook.

It was in retirement, and after her parents died, that she fell into a second career as a travel writer.

Having submitted a piece to a magazine called Contemporary Review, she was surprised one day to receive a complimentary copy containing her article, along with a cheque and a letter from the editor asking if she had any more ideas.

Irene’s eyes must have lit up – as they do now when recounting some of her travellers’ tales.

Most startling, perhaps, was her experience in a restaurant in Quito, capital of Ecuador, more of a private house really, where the owner, having taken the orders, remarked casually: “Oh, don’t be alarmed if a tiger walks in.”

“We thought he was joking but I think we were having soup when in walked a tiger.

“He stalked around and then suddenly I felt a great thump on my arm. I thought he’d attacked me so I screamed. Everybody else screamed and spoons clattered into the soup.

“The owner came hurtling back and hauled the tiger out before asking if I was hurt. I wasn’t particularly, although my dress was torn and a massive bruise developed.”

Thus the restaurateur’s role as a foster parent for orphaned tigers came to light. Irene suspects this orphan didn’t know its own strength.

As compensation, free liqueurs were offered.

“I always end this story by saying, ‘and that was the biggest and best Drambuie I have ever tasted’,” chuckles Irene.

She has never married but some interesting encounters with men are gleefully recalled.

In Papua New Guinea once at festival time, she had spent the morning visiting tribal camps and was watching some dancing in a grassy arena when she heard a voice and turned round.

“There was this fellow who was stark naked apart from a little bit of leaf and covered with greyish white clay.

“He said, ‘Have you got a light?’ I told him no because I didn’t smoke. It was a bit unnerving.”

Irene was delighted when her report of this won a competition in The Daily Telegraph.

Then there was the time she was on a camping expedition from Adelaide to Darwin and had just put up the tent she was sharing with a German girl.

It was right in the middle of Australia, the featureless Outback… well, apart from this one pub, all on its own.

“We decided to go and have a drink. We opened the door expecting it to be empty because it was in the middle of nowhere but it was absolutely heaving with men.

“So we elbowed our way to the bar and ordered our drinks and the chap standing next to me said, ‘What’s a Pommy Sheila doing in a place like this?’ It was the first time I’d been called a Pommy Sheila.”

What Irene and her companion hadn’t seen were the light aircraft parked in rows behind the pub. At the end of the evening, their Aussie companions offered to take them up the next morning at dawn.

“As we each got into these little Cessnas, I remember thinking we were barmy. Mad! But we took off and it was absolutely magical.

“Flying over the bush at dawn, you could see the wallabies and kangaroos. And you could see roads converging on the pub like the spokes of a wheel. It was a meeting place.”

The men eventually took off, leaving Irene and friend to make their way at ground level to Alice Springs.

What, you wonder, would Lydia have made of that?

Letters from Lydia by Irene Waters is published by Troubador Publishing.