Monet's magic makes an impression in South Shields

National Gallery masterpiece on show

The Monet is now in the building, as the sign outside South Shields Museum and Art Gallery indicates.

The Petit Bras of the Seine at Argenteuil is the third of the paintings to come our way as part of the National Gallery’s Masterpiece Tour, aimed at making its treasures more widely available.

It follows Constable’s The Cornfield, displayed near a pie shop in a Jarrow shopping centre in 2023, and Turner’s The Fighting Temeraire, centrepiece of an exhibition at Newcastle’s Laing Art Gallery the following year.

This latest touring masterpiece also has company.

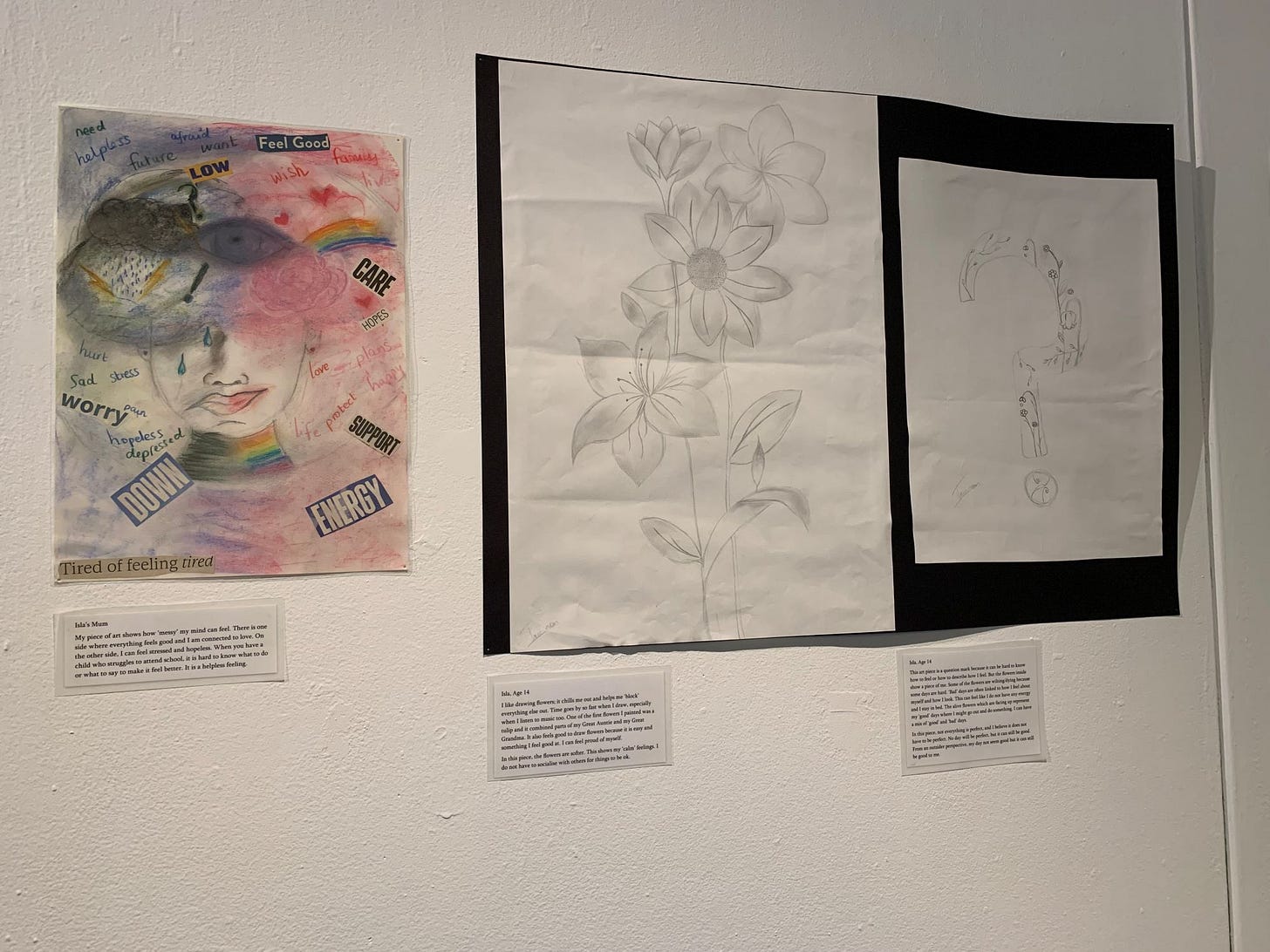

To reach the upstairs room in which it hangs, you pass through another where paintings from the North East Museums collection are displayed along with work done by young people experiencing EBSA (Emotional Based School Avoidance) who have been benefiting from a creative art project aimed at boosting confidence and wellbeing.

South Shields gallery manager Geoff Woodward said that in securing the National Gallery loan it had been important to explain the context in which it was to be shown.

So in advance of its arrival in the town, the painting and the artist have been studied and used as a spur to creativity. Those EBSA children, apparently more numerous since Covid, have clearly been inspired, along with their parents in some cases.

Claude Monet is famous for sunsets, poppies and water lilies dazzlingly executed, but this is a quiet painting, drawing you in rather than leaping out of its frame in a virtuoso blaze of colour.

Done two years before the groundbreaking first Impressionist exhibition in Paris in 1874, it shows a wintry scene beside a tributary of the Seine – mimicking, on the eve of the opening in South Shields, the misty greyness outside the gallery.

Two figures, or possibly just one with an easel, can be seen beside the gunmetal river. A slanting row of trees guides the eye down to them from the top right hand corner of the canvas.

Monet was suffering financial hardship at the time and not in the most robust frame of mind.

But it’s an important painting, stressed Geoff… “quite revolutionary in a sense because it was painted at a time when Monet was developing his Impressionist technique of capturing light on water, in the sky and the trees.

“He was interested in the natural landscape rather than artificial compositions and he painted en plein air (outside), not just sketching but creating finished pictures.

“That hadn’t really been done before. He changed the approach to landscape painting which then became less of a secondary subject for people. A real interest developed in capturing the natural world as it was.”

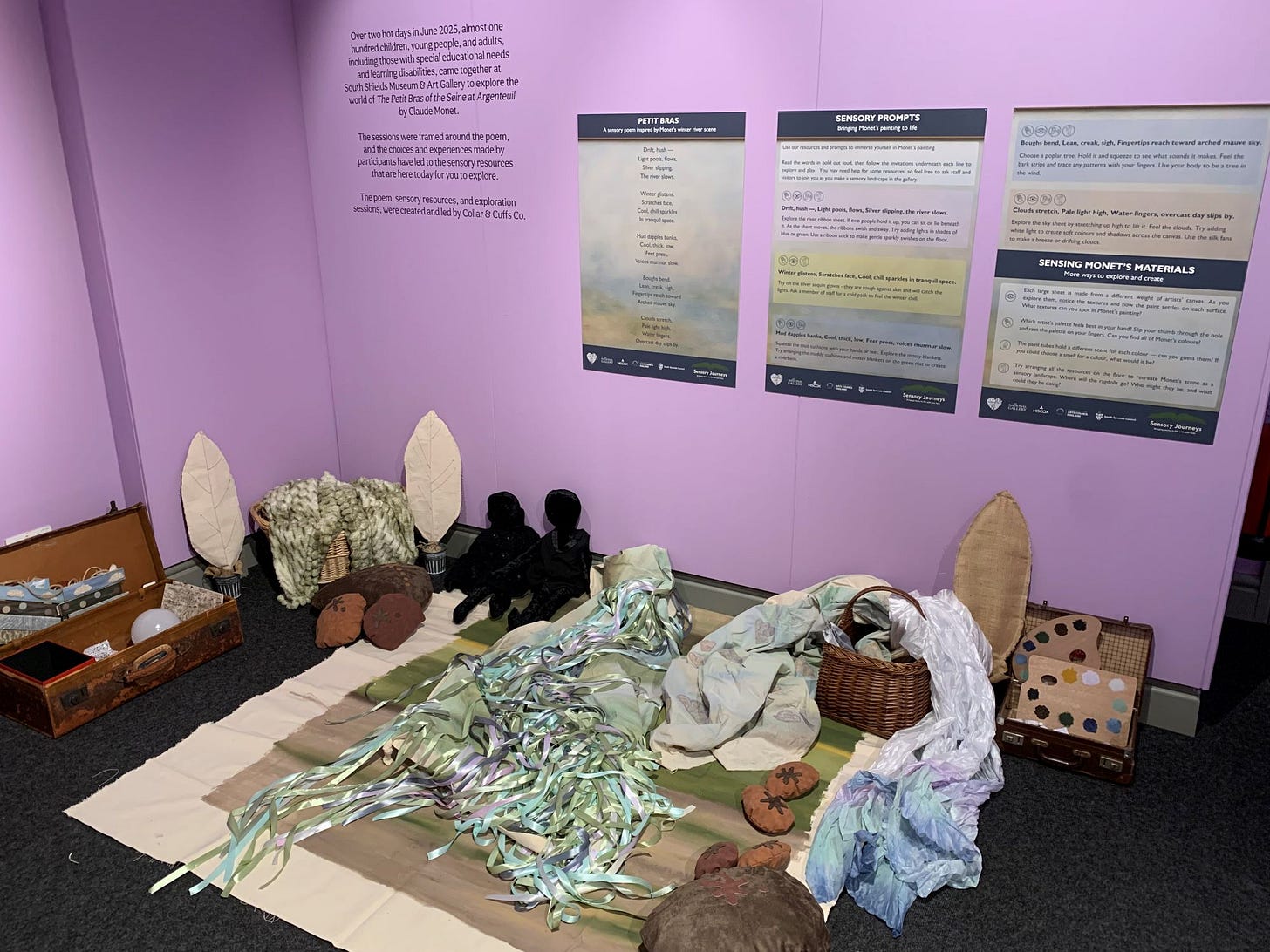

With plenty of easy-to-read text on the walls, it’s an appealing exhibition over two rooms with the Monet – modest, under-stated yet still with an aura of celebrity – in the second of them, accompanied by some hands-on props for creating Monet-style 3D landscapes.

Before you enter the hallowed presence, there are those other absorbing pictures to look at, including some showing North East scenes at about the same time as the Monet painting was executed.

We learn that South Shields and the French town of Argenteuil, where Monet was living at the time, weren’t wholly dissimilar in the 1870s, both being developing industrial centres on the banks of a major river.

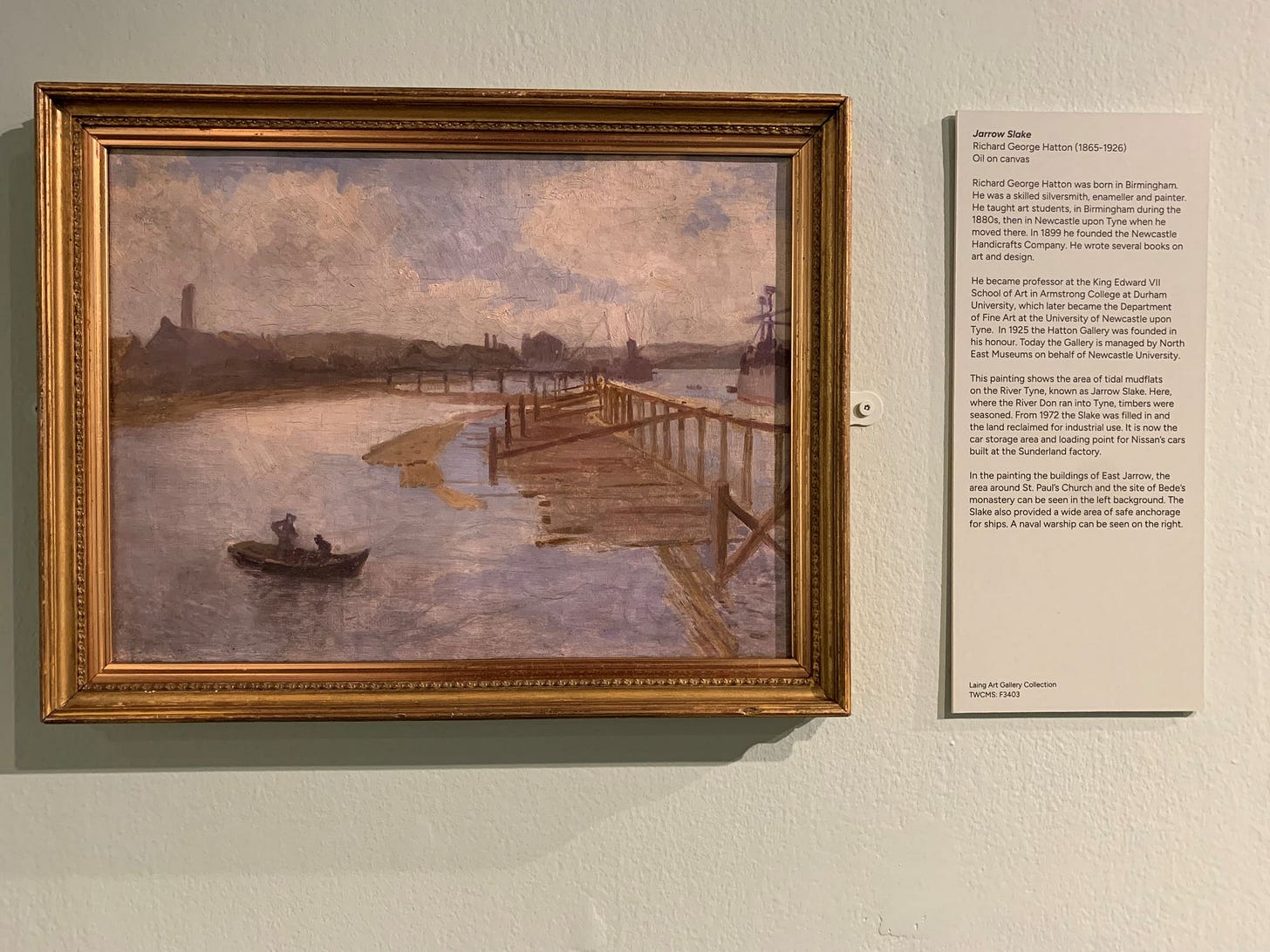

The oil painting Jarrow Slake by Richard George Hatton (professor at what became Newcastle University’s fine art department and after whom the Hatton Gallery is named) shows a similar watery scene with two men in a boat positioned where Monet’s figures are.

There’s a painting called simply Landscape by French artist Jean-Baptist-Camille Corot (identified as being by the artist rather than one of his followers while being cleaned and analysed in preparation for this exhibition) whose work was admired by Monet.

Both Monet and Charles Napier Hemy (born in Newcastle in 1841) at one point in their lives worked in studios made from converted boats, as you’ll learn in the caption to Hemy’s The Last Boat In, showing a fishing vessel on an extremely busy looking River Tyne.

Monet’s advice to a fellow artist, the American Lilla Cabot Perry, written here on the wall, encapsulates his artistic approach.

“When you go out to paint, try to forget what object you have before you, a tree, a house, a field or whatever, merely think, there is a little square of blue, here an oblong of pink, here a streak of yellow, and paint it just as it looks to you, the exact colour and shape, until it gives your own naïve impression of the scene before you.”

That’s Impressionism in a nutshell and its appeal, after initial scepticism, has stood the test of time.

And should you wish to know more, it’s worth making a diary note of an exhibition coming up at the Bowes Museum, Barnard Castle, later in the year (September 26 to March 14, 2027).

Called Impressions of Light, it will feature paintings by Monet and other Impressionist and post-Impressionist artists and is the result of a partnership between the Bowes and the Musée d’Art Moderne André Malraux (MuMa) in Le Havre.

But the National Gallery’s treasured Monet masterpiece can be seen at South Shields Museum and Art Gallery until March 25.

The gallery opens Monday to Friday, 10am to 5pm, and Saturday, 11am to 4pm. Admission is free (donations welcome). For details of activities related to the exhibition, go to the museum website.