Memories stirred as Fish Quay tavern lands a lost treasure

Restored to its rightful place over the fire is a painting of the Abergeldie 391... no ordinary North Sea trawler

Drinkers at the Low Lights Tavern, traditionally a fishermen’s watering hole on North Shields Fish Quay, have got their artwork back.

It was unveiled over a lunch of pints, pies and poignant memories – plus a few painful ones - in a pub brought back to life by Danny Higney.

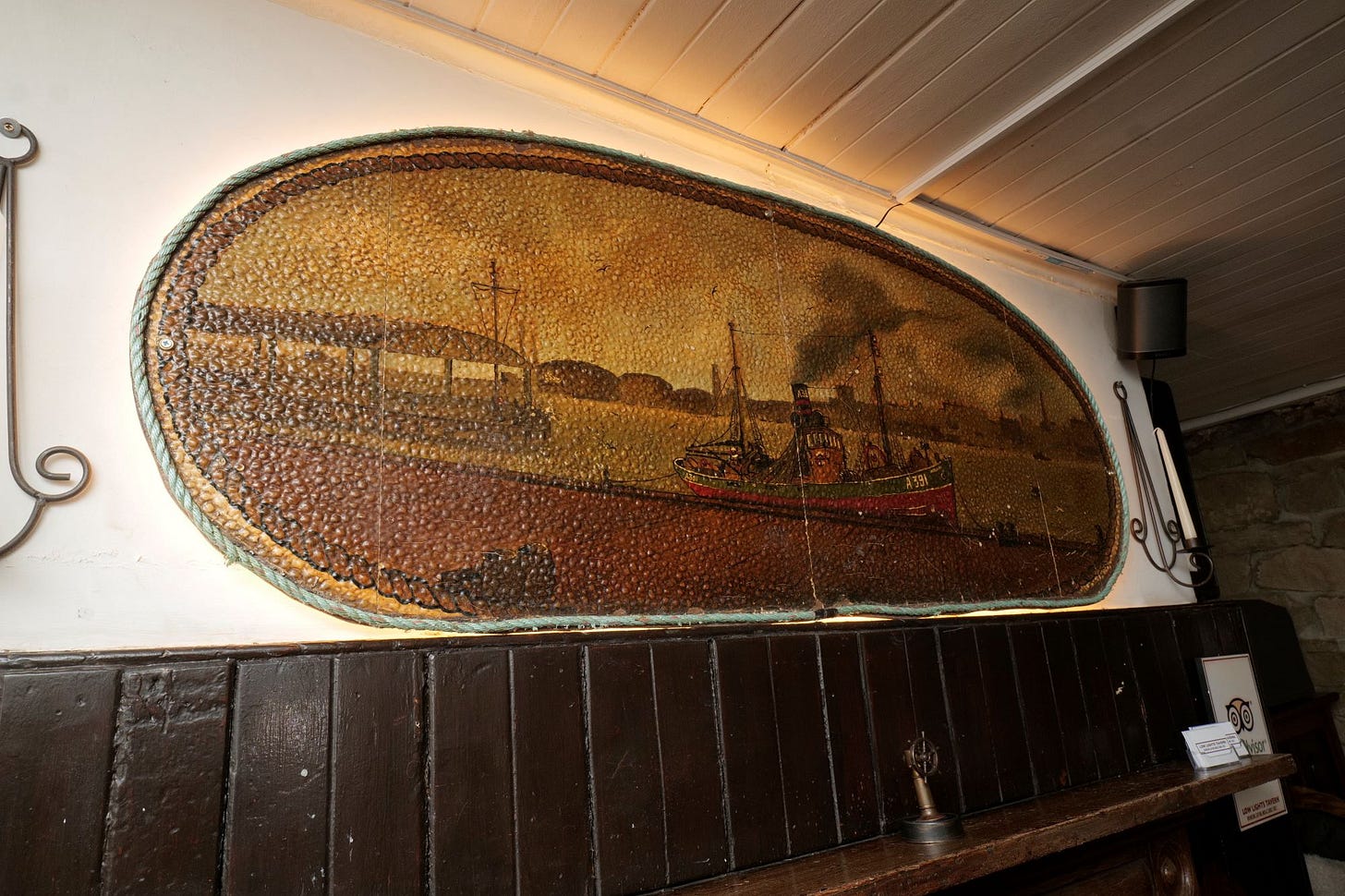

There it is above the hearth, where a fire blazes on a cold day, a painting of nearby Western Quay with a fishing trawler moored alongside.

You might have thought the Low Lights locals might have sought a bit of escapism through art, something a bit less fishy or nautical, perhaps.

But the pub, reputedly the oldest in North Shields, has been at the heart of a fishing community for 400 years. The sea has sustained life in this place, effectively been its world.

And in any case, it’s unlikely they had any say in the matter when, back in 1956, Eddie Rowley stood on a chair and painted his Fish Quay scene directly on to the anaglypta wallpaper.

Eddie was a local painter and decorator whose grandfather, back in 1925, had painted the rooms of the pub, as verified by the accounts of the family firm, Fleming’s.

But Eddie also had an artistic side and his mural over the fireplace, showing Western Quay and the trawler Abergeldie 391, became a popular fixture.

And it was a fixture. A bit like Banksy’s creative efforts, if you’re going to remove the artwork you have to remove the thing it’s attached to, most often a wall.

When the Low Lights Tavern fell into disrepair in the early 2000s after suffering a downturn in its fortunes, regular customers assumed the painting had been destroyed.

That was certainly what Danny Higney heard when he took over the place in 2016 and started to breathe new life into it.

But last year brought extraordinary news. The painting had resurfaced.

Instead of being destroyed, it had been snipped from the surrounding wallpaper, mounted on plywood and saved, Banksy style… and now it had been found by a local fisherman while clearing his loft.

The precise whys and wherefores of the story are shrouded in a bit of a sea mist but the upshot is that Eddie Rowley’s painting is now back where it belongs, though hung on the wall rather than as part of the wallpaper.

Publican Danny knows what this means to people.

“I was over the moon to have the painting returned as it was much revered by many of our local fishermen back in the day,” he said.

He asked local artist Mark Taylor to make it shipshape again and then organised the launch event which saw the pub packed to the gunwales, as it often is these days.

It was, he said, a “treasured piece of our history”.

Also thrilled was Terry McDermott, chairman and co-founder of the North Shields Fishermen’s Heritage Project, who did the unveiling and whose daughter, Kerry Hayes, sang a sea shanty.

“I’m overjoyed to see it back,” he said.

“It’s another sign of the pub coming back to life again. All the old lads who used to drink here will love to see it back there. It’s bringing back the nostalgia and heritage.”

Eddie Rowley is no longer with us, sadly, although his daughter, Judith, was among those who gathered to see the painting unveiled.

The Abergeldie, built in Aberdeen in 1915, is long gone.

Terry said it was an ordinary trawler, not famous for anything in particular. It was one of many owned by Richard Irvin who ran trawlers out of North Shields and Aberdeen and just happened to be there when Eddie was painting the view.

Talk of trawler owners makes Terry’s face cloud over.

They’d take 50% of the proceeds of any catch, he explained darkly. Then they’d pay for diesel, food and everything else out of the remaining 50% before releasing what was left to be divided among the “share fishermen” who made up the uncontracted crew.

No catch meant no pay and lives risked for nothing at all.

“You should speak to Tom Webb,” said Terry.

So I did and realised that for one man at least, the vessel Eddie portrayed was no ordinary trawler.

Tom, aged 89 now and living in South Shields, remembered volunteering to be relief third hand on Abergeldie 391, standing in for a man who wanted time off over Christmas.

Out of work at the time, he had been glad to go to sea in the vessel skippered by a man called Sam Cullen whose brother, George, served as mate.

More than 100 miles off the North East coast, with a substantial catch of fish in the net and in a heavy sea, the worst happened.

The fishing parlance that has enriched our language would seem to be going the way of the industry – but Tom explained that having attached a becket, a kind of bag as I understand it, over the business bit of the net, the codend, he was trying to haul it in with a Gilson hook.

Leaning over the side, he was in no position to respond when the skipper yelled from the wheelhouse: “Look out for the water.”

Others leapt for their lives. Tom, a young man with much to live for, found himself lifted up and away by “a mountain of sea”. It was Christmas Eve.

“I was whipped straight into the sea, no mucking about,” he said.

“Then I found myself floating away and I could see the ship going up and down with the swell. I’d lose it and then see it again.

“It’s a horrible, horrible feeling. You’ve got your sea gear on and fortunately I had a yellow sou’wester. If I’d had a black one, they never would have found me.”

Having located him, eventually, the Abergeldie drew alongside and George Cullen attempted to pull Tom aboard, only to lose his grip and for the sea to suck him back again.

“It was very frightening,” said Tom.

“For the second attempt, the skipper said to his mate, ‘You come up and take the wheel and I’ll see if I can get him this time’.

“So George went up and Sam came down. Now this guy Sam had had his fingers blown off during the war. He only had two left but he managed to hook them in the neck of my oilskin and pull us on board.”

Even now Tom shudders at the memory. It wasn’t often men were rescued in such circumstances, he reckoned. “There were no other trawlers around at the time, no lights, nothing.”

He attributes his survival to his yellow sea gear, the airlock within his jacket – formed by accident rather than design – and possibly the strongest two fingers ever deployed off the North East coast.

Taken below deck, saturated and freezing, his fellow crew members stripped him, rubbed and pummelled him and got a tot of rum down him. They then donated items of dry gear for him to put on.

Thoughts of staying in the warm for a while to recover were swiftly dashed, however.

“I had to go straight back on deck. That was the skipper’s instruction.

“I wasn’t happy at all about that at the time but I believe it was the making of me. I think I would have lost my nerve otherwise because the seas were really bad.”

So for Tom Webb, the Abergeldie will always be more than just an ordinary trawler and a picture on the wall.

He gave up the seagoing life eventually, he said, when another trawler he was on, the Ben Lora, capsized on its way to the Faroe Islands. It righted itself again in heavy seas but Tom decided he’d been lucky twice and that was enough for him.

But at the Low Lights Tavern, the memories came flooding back on a tide of pleasure as well as pain.

“This is exciting for me because I don’t get much excitement in my life now,” Tom said with dry (mercifully dry) humour.

“It’s nice to listen to the lads and have a little bit crack.”

The dancing girls, promised Terry, no less drily, would be along shortly.