Last chance to see stirring paintings by Sheila Fell

The Cumbrian fells come alive in Sunderland

It’s ridiculously late to be telling anyone how good the Sheila Fell exhibition is at Sunderland Museum and Winter Gardens – but there are still a few days left (it closes on Saturday) and it wouldn’t be a wasted journey.

It originated in Carlisle, at Tullie House, and I decided to wait and see it in Sunderland where it opened in April.

Then, of course, stuff happened and then yet more stuff. But better late than never.

The Tullie House setting was perfect because it once housed Carlisle School of Art where Sheila was encouraged by a teacher to enrol at the age of 16.

For the daughter of a coal miner and a seamstress, born in 1931 in Aspatria, Cumbria, it wasn’t the happiest of experiences, but when she moved to London and Saint Martin’s School of Art in 1949, things started to happen for her.

One thing that happened was LS Lowry who bought some paintings from her first London exhibition and then supported her financially, sending her £3 a week to keep her going.

It seems an unlikely friendship, he being an older man in a raincoat and she being a bright young thing who had been keeping body and soul together by working in cafes and a nightclub and doing some modelling from the neck up.

But apparently he liked to watch her paint and they shared a certain outlook and sense of humour.

The Sunderland exhibition setting is also perfect because Sheila Fell’s paintings are displayed in a room just across from the Lowrys.

Both artists revelled in a very English type of bleakness, nothing ‘chocolate box’ about either of them, but Lowry’s rendering of it was often understated (just a few lines on paper) or full of controlled bustle (all those matchstick figures).

Fell clearly loved nature and paint, often lashing it on so thickly that it congealed into great swirls and lumps. Yet out of the lumpiness emerged barns and cows and soaring fells and huge rain-filled clouds.

There’s a lot of snow, too, as there would have been in Cumbria when she was growing up, and many of her paintings mimic Lowry’s in their whiteness, although his bleached expanses were more for effect than wintry exactitude.

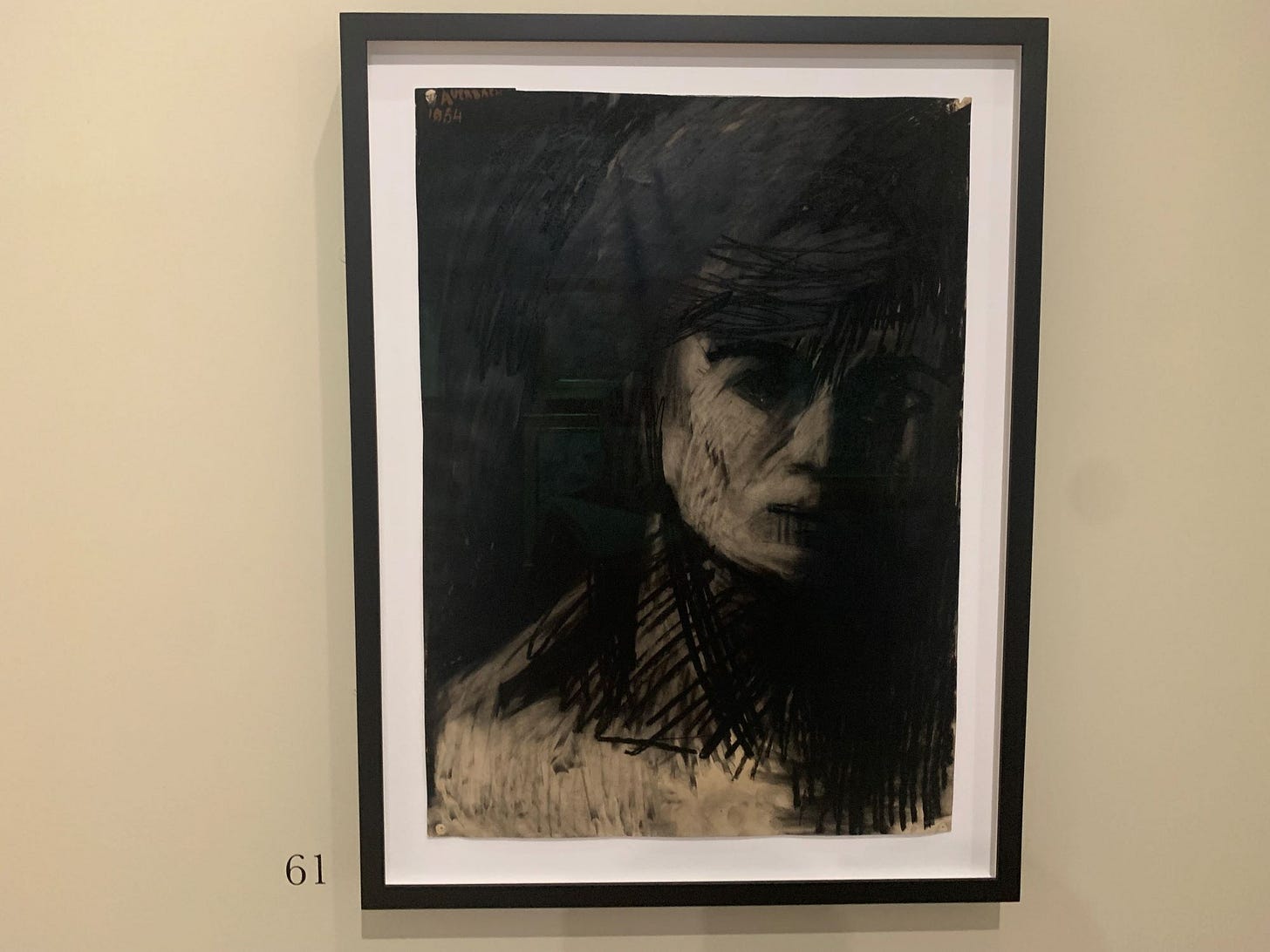

Lowry loved Sheila Fell’s work and so did many others. There’s a portrait of her in the exhibition by Frank Auerbach who is known for the lavishness of his paint but who also captured likenesses in charcoal.

You sense he got her to a tee in this one, capturing a shrewd and perhaps defiant look beneath the hair. They were friends embarking on their careers at around the same time.

“Sheila Fell’s passionate involvement with the landscape around Aspatria, and her talent and industry, have assured the survival of her work,” he said at one time (the quotation’s on the wall).

Auerbach died in London, aged 93, just a few days before her exhibition opened in Carlisle.

Sheila Fell died in 1979, shortly after telling the Sunday Times journalist Hunter Davies – who owned some of her paintings – that she planned to live until she was 104.

The inquest decided alcohol poisoning. Davies reports that, with horrible irony, she fell down the steep flight of stairs he had described in his article. They are not mutually exclusive occurrences. She was only 48.

She left a lot of wonderful work, capturing the colour and dynamism of the northern landscape – which continued to inspire her even after she had settled in London – and the hardiness of the people who lived and worked in it.

Sheila Fell: Cumberland on Canvas is at Sunderland Museum and Winter Gardens, Burdon Road, until Saturday, June 28. Admission is free. Do see it.