'I’ve done loads of thrilling things but this is what I’m most proud of'

Never drawn to places where bullets fly, Phil Murphy recalls a bloody conflict in his debut novel. He told David Whetstone why he wrote it

Phil Murphy wants to make one thing clear. He never had any desire to be near people firing guns. Growing up in Newcastle, he didn’t want to be a war correspondent any more than he wanted to be a soldier.

Imagine his trepidation, then, having landed in Sarajevo with John Major in 1996, on being told that although the four-year siege of the city was officially over, the odd trigger-happy sniper might still lurk in the hills.

You don’t have to imagine it. He recalls it vividly, having survived to tell the tale.

“A sniper can get you from about a mile and three quarters away. I remember thinking: why are you telling me this? What could I do about it?”

This he relates to me in a Newcastle pub. In the early 1980s, as fellow reporters on The Journal, we were often in pubs.

Then came a parting of the ways. I stayed in Newcastle, Phil went to London, covering events at Westminster for regional newspapers before becoming political editor of the Press Association.

Read more: Region’s musical heritage to be celebrated in new show

In that capacity, having covered the turbulent Thatcher years, he would tag along with Maggie’s successor John Major and later Tony Blair on their overseas trips.

When Major went to the Kremlin to see Boris Yeltsin, Phil went too. He also recalls an awkward press conference at the White House with President Clinton and Prime Minister Blair after the Monica Lewinski sex scandal had broken.

Once, in a PM’s wake, he travelled through the Khyber Pass on Pakistan’s border with Afghanistan. “Fantastic – one of the most thrilling things.”

But it was that Sarajevo trip that stuck with him and is the reason we’re reunited in a Newcastle watering hole.

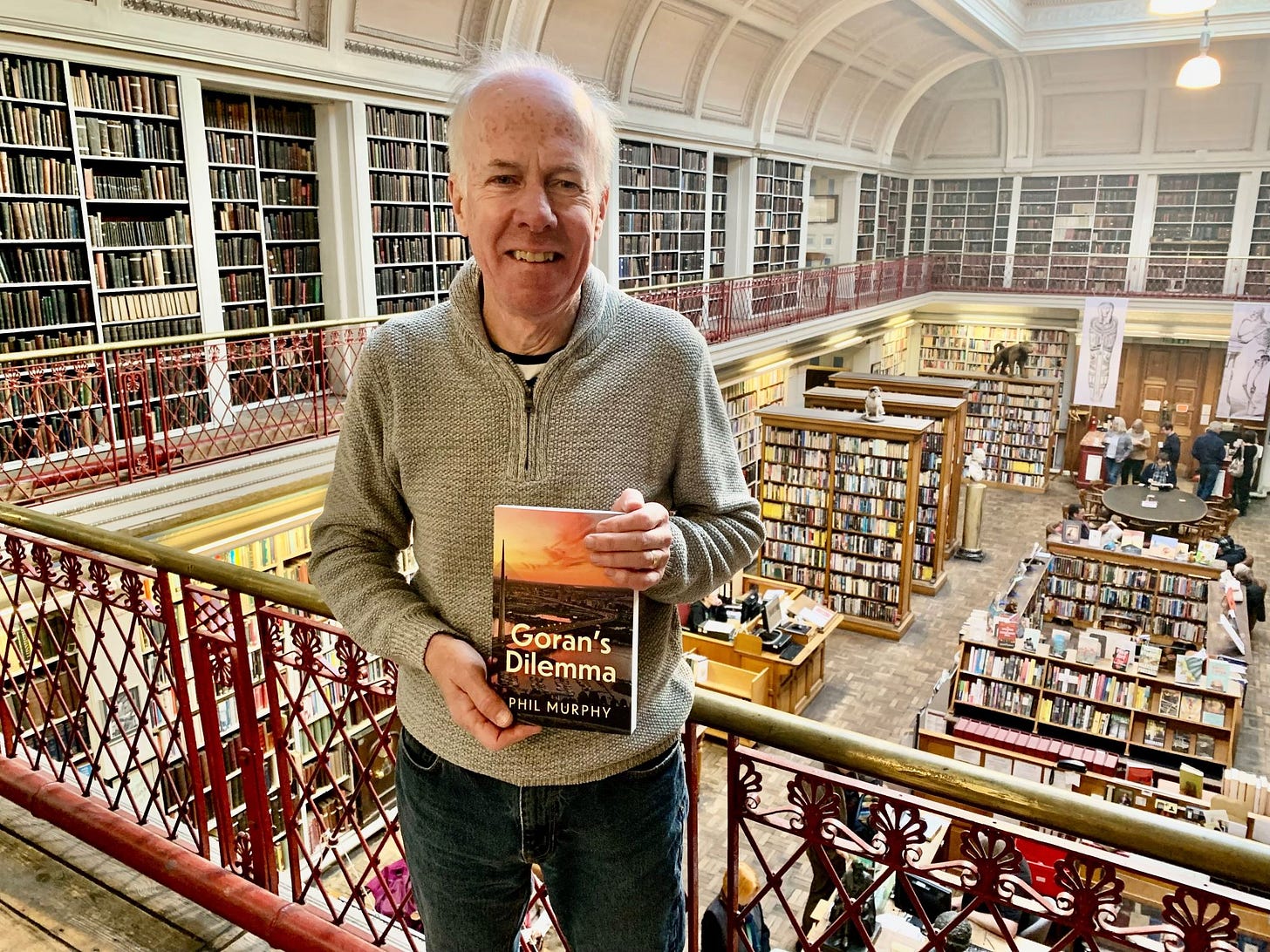

For if war correspondent wasn’t among Phil’s ambitions, novelist was – and his first novel is published this week.

It’s called Goran’s Dilemma and it’s a cracking yarn set against the bloody wars of the early 1990s which saw Yugoslavia shatter into its constituent parts.

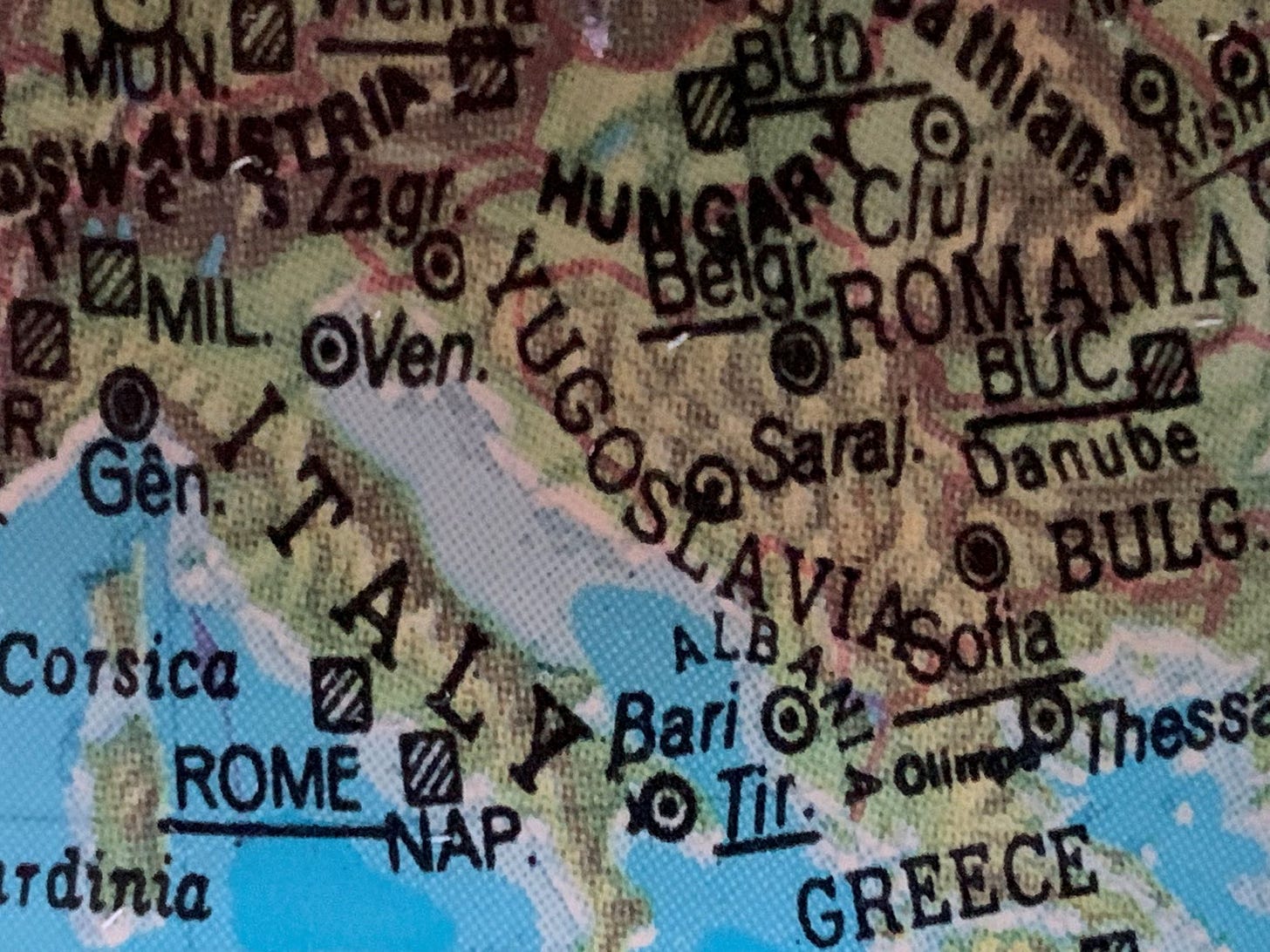

Comprising states mashed together after the First World War, first as a kingdom and then a communist republic, internal strains became critical after the death in 1980 of Marshal Tito, its leader and one-time revolutionary.

A decade later all hell broke loose in that part of Europe referred to airily as the Balkans but now comprising Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia, Kosovo, Montenegro, North Macedonia, Serbia and Slovenia.

Many thousands died in the overlapping ethnic wars which put concentration camps, genocide and mass graves back in the headlines.

For four years Sarajevo, capital of Bosnia Herzegovina, was a killing field, bombed and sniped at by Serb forces.

“I was only there a couple of days,” says Phil, “but I remember there was hardly a pane of glass left.”

The experience shocked him but he came to love that part of the world. He has visited many times, deeming Bosnia “one of my favourite places.

“The northern bit’s flat and light industrial but central and southern Bosnia is fabulous.

“I really like the mountain villages. There’s a place called Jajce which has beautiful waterfalls. It’s where Tito attended the founding of the Yugoslav communist party.”

A bit of a linguist, Phil can now get by in Serbo-Croat, although he says many people he meets prefer to converse in English.

His novel is no misty-eyed travelogue. Blending fact and fiction, it revives memories of Ratko Mladić, the brutal Bosnian Serb officer responsible for the Sarajevo siege and convicted of war crimes at The Hague in 2017.

It also concerns his daughter, Ana, who in 1994, at the age of 23, shot herself with her father’s pistol.

“It’d be great if it sells well but the main thing is having it out there. This is me saying, guys, don’t forget about this.”

Goran is the boyfriend she may or may not have had. Phil says experts are divided over whether he existed, but he has used him as a way into his story about a “father-daughter axis and its consequences”.

“As best as I have been able, comments assigned to Ratko are based on actual interviews or recordings,” he says.

“There is no record in any location of Ana’s words or reflections.”

He has done his best to ensure that the historical details are accurate, with other fictional characters serving as “the vessels through which I seek to capture the essence of the cruelty and compassion that characterised the conflicts of 1991-5”.

He has visited Ana’s grave – “like looking for a needle in a haystack” - and seen the Mladić family home

Anger infuses the way he writes and talks about what happened. He doesn’t want it to become Europe’s forgotten conflict.

“Sarajevo is a multi-cultural, multi-ethnic city with strands of history running through it,” he says.

“I thought how can this be, that this European city can be bombarded for more than four years?

Read more: Heartwarming Christmas show, Present returns from past

“Mladić is on record as saying its people should be bombed to the edge of madness. If it had been Venice or Milan it would have started on a Tuesday and been finished on the Friday.”

Phil, a father of two who now lives in Surrey, says his anger was not eased by the many books he has read on the subject. This country and others, he believes, didn’t behave wholly honourably, washing their hands of things to a degree.

He spoke to the late Paddy Ashdown, ex-Royal Marine and one-time leader of the Liberal Democrats, who also loved Bosnia and had urged passionately for military intervention to stop the bloodshed.

“He shared his observations about Mladić but also said not to buy this line that they’re all mad in the Balkans and like fighting.

“He said it’s rubbish and no different to what he witnessed as a young squaddie in Belfast. The reality was that the veil between civilised and uncivilised behaviour is thin.”

Phil’s career took him from journalism into politics, as special adviser to Tony Blair for a time, and finally into the corporate world. When he retired in 2017, he was able to dedicate himself to the novel.

“A sniper can get you from about a mile and three quarters away. I remember thinking: why are you telling me this? What could I do about it?”

And in its first draft it was huge. He laughs at the response of a published novelist who had been asked for her honest opinion.

“She said it was far too long. ‘The writing is good but you’re basically writing for the 200 people in the UK who are as interested in Yugoslavia as you are’. She thought it was a bit heavy.”

Back to the drawing board, Phil rejigged things and one novel became two.

The first, Goran’s Dilemma, with Ratko and Ana Mladić at its heart, will be followed next year by The Pavelic Trap which tells more of the wider conflict with a journalist as its main character.

“I’ve done loads of thrilling things but this is what I’m most proud of,” Phil says of his first foray into fiction, published, as its successor will be, by Troubador.

“It’d be great if it sells well but the main thing is having it out there. This is me saying, guys, don’t forget about this.”