Hexhamshire history explored in new book

Historian and author Greg Finch will give an online talk today (Thursday) after embarking on a centuries-long tour of his home patch in Northumberland. Tony Henderson reports

It’s a calm corner of Northumberland where the lowlands meet the uplands.

Hexhamshire extends across 26,500 acres and 40 square miles of the area between the Tyne Valley and the North Pennine fells.

It is also home to author and historian Greg Finch, who has extensively researched the area whose boundary is the catchment of the Devil’s Water valley.

Hexhamshire has seen great changes over the centuries and Greg will expand on how people have used its resources and left their mark in a Northumberland Archives online talk on Thursday November 21, at 7pm.

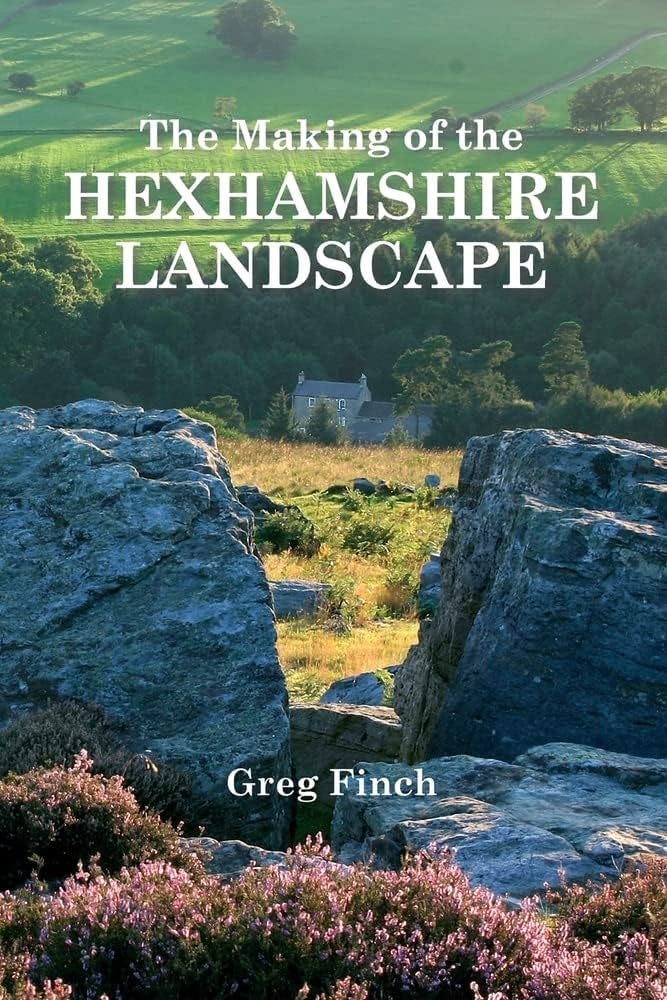

The event will be based on Greg’s studies for his most recent book, The Making of the Hexhamshire Landscape, published by Hexham Local History Society at £15. It follows his book two years ago on the exploits of the influential Blackett family of Newcastle.

Read more: Review - Dear Evan Hansen at Sunderland Empire

Greg says: “Hexhamshire is a place of transition between lowland and upland and in some ways is a good area to look at landscape history. It had a range of different types of country and is quiet and a bit off the beaten track as there are no through roads.”

Early history suggests that Hexhamshire farming would have provided goods for the Roman town of Corbridge.

The later lead industry certainly made its mark, with the Dukesfield smelting mill almost certainly the biggest of its type in Britain in the 17th century.

Parcels of lead ore were carried to the mill by pack ponies from distances of 25 miles and more. Hexhamshire became an attractive location for smelting from mid-17th to the early 19th centuries.

The area alongside the Devil’s Water and Rowley Burn was, says Greg, a bustling dirty, polluting, and noisy industrial cluster “far removed from today’s quiet pastoral landscape.

“Due to its location, the Shire was a busy crossroads of long distance traffic between mines, mills and markets and livestock on the hoof between northern pastures and London,” he says.

The drive for land improvement attracted interest from outside during the 17th and 18th centuries, and three large estates were created in the Shire.

The players included the Blacketts, the Claverings, and the Radcliffes of Dilston although James Radcliffe, the Earl of Derwentwater, was executed after his lead role in the north in the 1715 Jacobite rebellion with his lands confiscated and going to the Royal Hospital at Greenwich.

Between them the three estates accounted for around half of the Shire’s enclosed and improved land in the mid-18th century.

The enclosure of large areas of land after 1750 had a dramatic effect. “Much of the field and road layouts we see today date from five decades after 1750,“ says Greg.

Sit Walter Blackett was a prime mover in the enclosure of Hexham East and West Commons.

“A rising population and increasing industrialisation, demanding more food and raw materials, lay behind this extraordinary burst of activity,” Greg adds.

By the end of the 18th century output from the mines and mills in the area had more than trebled in 50 years.

Another change in the landscape was the building of chapels – 30 between 1840 and 1875 - while conifer plantations were being laid out to provide bark for tanning for Hexham’s growing leather trade.

A response to a Victorian agricultural depression saw estates turn to grouse shooting. Country retreats were also built, such as Duke’s House for Darlington banker Edward Backhouse, Stotsfold Hall for the Mounsey family of Sunderland shipbuilders and Linnels House for the Charltons of Cullercoats.

The 1890s also saw the establishment of Hexham Racecourse on the Yarridge estate by the County Durham industrialist Charles Henderson.

In recent times, multi-purpose concrete and steel farm sheds have appeared and silage bales of silage dot the landscape.

“The heavy footprint of modern agriculture is often bemoaned but its adaptation to today’s markets and constraints is only the latest in a long history of flexibility and change seen over millennia,” says Greg.

“Today’s new structures are a further contribution to tomorrow’s landscape heritage alongside rig and furrow cultivation, thorn hedges, drystone walls post and wire fencing, Georgian farmhouses and Victorian byres.”

Part of the Shire lies within what was another relatively recent development, the designation of the North Pennines Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty, now termed National Landscapes.

Greg says: “We are essentially preserving just the latest remodelling of the land. Our landscape will keep on evolving. The current snapshot will be replaced by another.”

Sign up for Greg’s online talk tomorrow (Thursday, November 21) here.