Exhibition raises questions about our colonial past

International artists unite in Newcastle

Pink footprints on linen, colourful drawings by children, a sound sculpture and a screen that looks metallic but comprises tiny folded diary notes – all are part of a rather beautiful exhibition at Great North Museum: Hancock.

It’s something of a paradox, too, being an exhibition in a museum that asks us to reflect on what should be in a museum – and where.

And because it’s the latest public sharing of work by Newcastle-based visual arts producers D6: Culture in Transit, you know this is the tip of an iceberg.

Furthering its belief that “art can help to create a kinder and better informed society”, D6, under founder and executive director Clymene Christoforou, works in a collaborative way, helping to facilitate art exchange programmes, research residencies and international projects.

Exceptionally well connected overseas, it is part of Contested Desires: Constructive Dialogues, an international programme involving 22 artists and 20 arts and heritage partners spread throughout Chile, Cyprus, Ghana, Hungary, Italy, the Netherlands, Portugal, Slovenia, Spain, Tunisia and the UK.

The programme is focused on the legacy of European colonisation – the “problematic” legacy, as they call it, resulting from many centuries of plundering and exploiting in the name of empire building.

Say the Contested Desires: Constructive Dialogues partners: “Citizens are rightly calling into question the connection between the past and the present, interrogating the ways that national identities are crafted and systems of oppression are upheld.”

The exhibition in Newcastle is part of the mission “to build a shared understanding of this colonial past and what it means to different people”.

There was also a Contested Desires conference at The Word in South Shields on July 17.

The exhibition at the GNM: Hancock features work by seven artists and some of those they’ve worked with on their various residencies around the world.

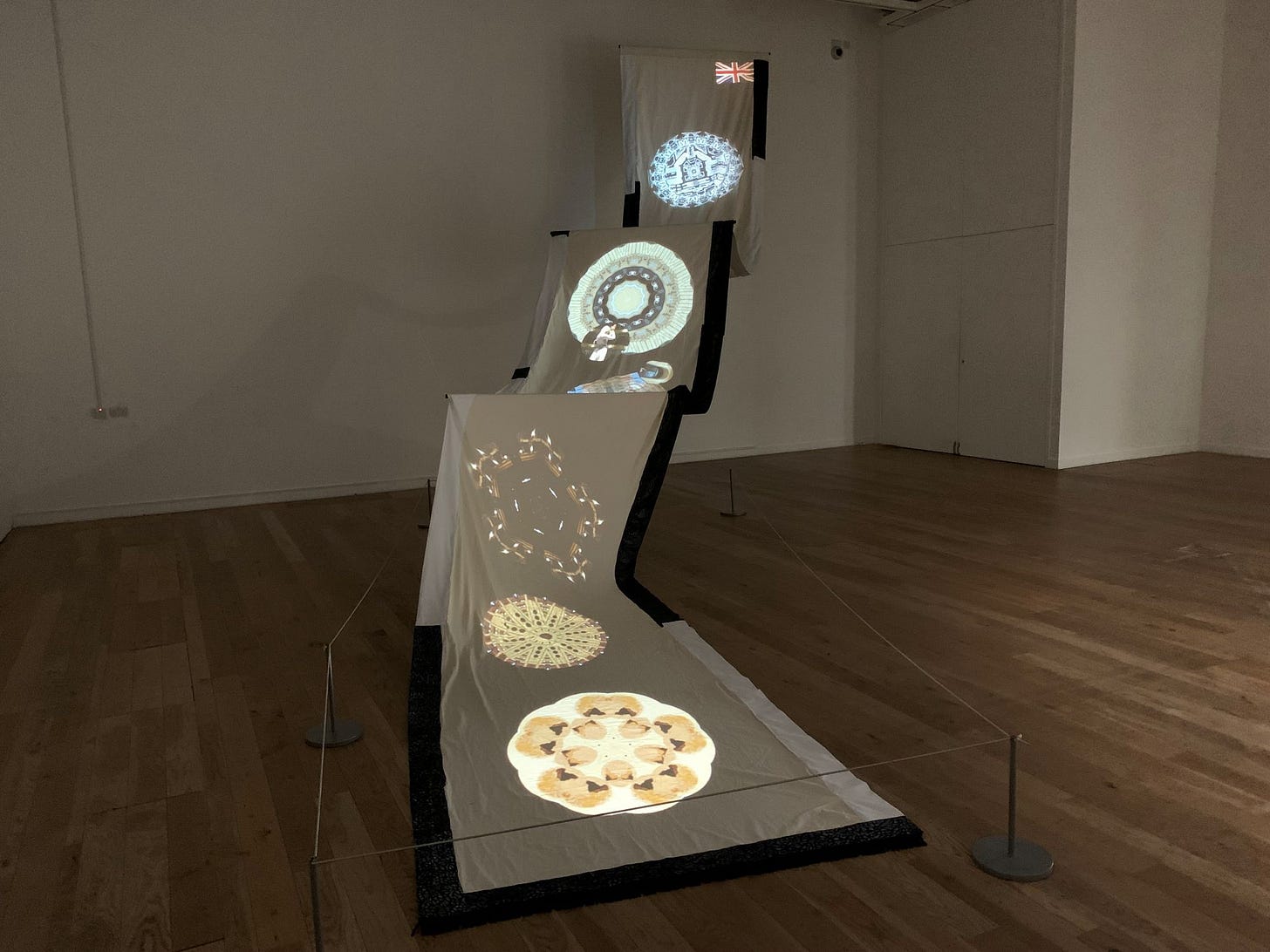

In the first of the two rooms, under subdued lighting, you won’t be able to miss the fabric piece by Ghanian artist Elisabeth Efua Sutherland who spent time in Newcastle researching the stories of black and African people who have visited it and, in some cases, settled here.

The circumstances of Zuza Ben-i-Ford’s journey to the city might be a little hazy now but it is established that she was one of the residents of a mock ‘African Village’ feature at the North East Coast Museum of 1929.

And it is known that she died in Newcastle and was buried in an unmarked grave. There had been protests about the village but none that really struck home.

Elisabeth also looked into the life of Arthur Wharton, a footballer who came from the Ghanian capital, Accra, where she runs an art space, to play for Darlington.

Her research fed into the creation of a long, undulating banner which goes from from ceiling to floor, alluding to Asafo artwork from Ghana and referencing a line by anti-slavery campaigner Frederick Douglass, who visited Newcastle, “as with rivers, so with nations”.

Nearby is work by Rafael Guendelman Hales, from Chile, a visual artist and documentary filmmaker who has worked in the North East but also at the Museo della Civiltà (Museum of Civilisations) in Rome.

There he was struck by the maps and diaries of colonial explorers in Amazonia and East Africa.

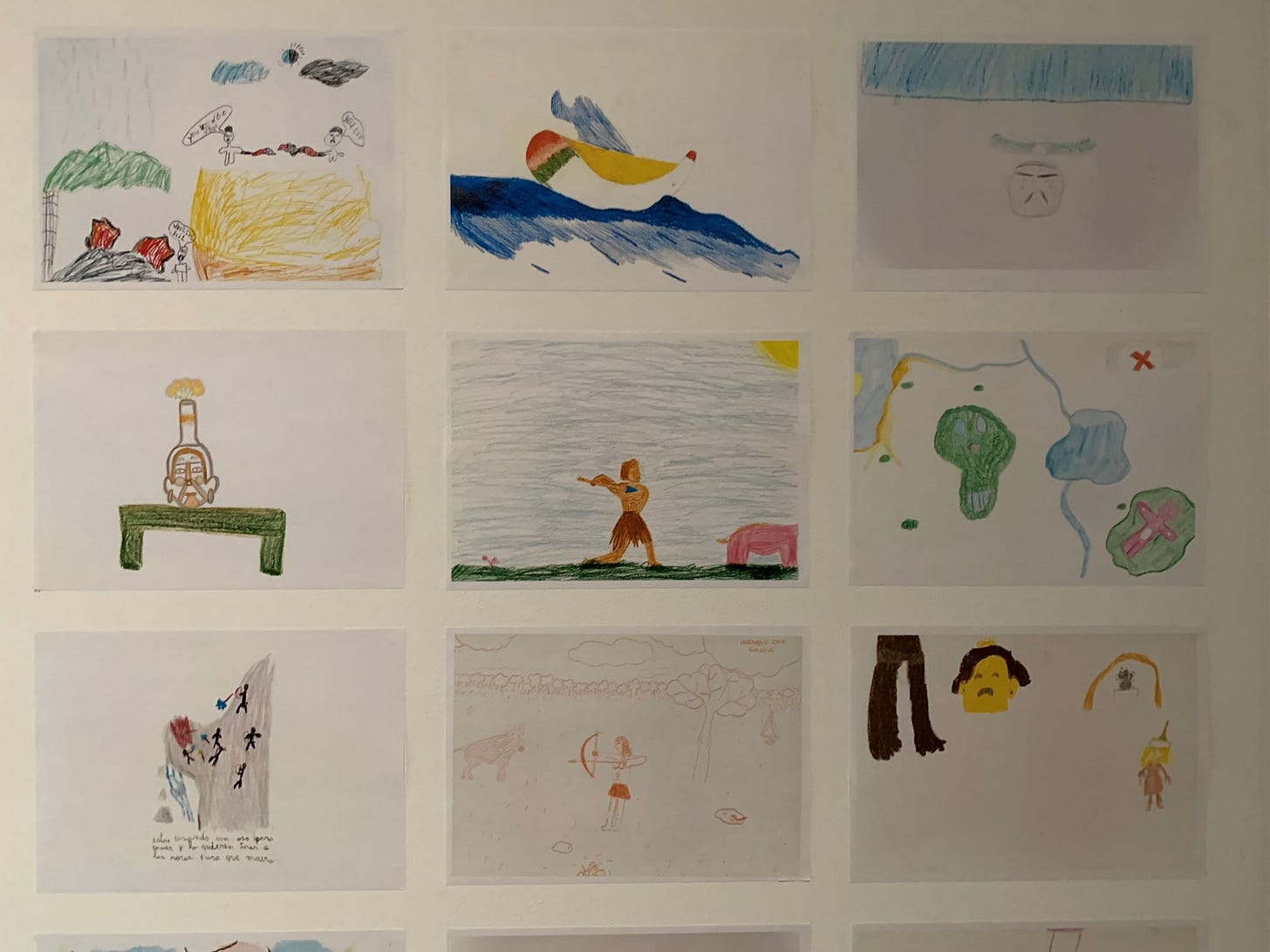

He is working with children in Rome, Santiago and Newcastle to create an animation about a fictional explorer and the contradictory nature of exploration in places already inhabited.

Children were asked to think about museum objects and depict how they might be displayed in their country of origin. The results are in the drawings we see.

Next door is that eye-catching screen made by Isaac Nana Opoku who represented Ghana at the 2022 Venice Biennale.

In response to the colonial collections at the Museo della Civiltà, Isaac created the textile screen which comprises a succession of interconnected squares, each an “encrypted vessel of meaning”.

Each, we are told, captures a moment of insight, discomfort and revelation in much the same way that traditional African textiles feature coded designs.

His Tapestry of Encrypted Memories is part of a drive to “decolonise imagination”, we are told. It’s certainly an intriguing and intricate piece of art.

Also in this room is Tracepace by Rwanda-born Patrick Ziza who is based in Gateshead and London and did a residency at the Museum of Memory and Human Rights in Santiago, Chile, which commemorates victims of dictator General Pinochet’s regime (1973-90).

It’s an evolving artwork bearing physical traces of people - those footprints - and commemorating human rights campaigners.

Another UK-based artist, Paul Nataraj, exhibits a nine-channel sound installation incorporating recordings he made during his residency in Budapest.

His work, says D6, “explores the intersections of sound, materiality, memory, diaspora and identity” and is grounded in ethnographic research and biographical storytelling.

There’s a film by Italian performance artist Maria Luigia Gioffre which is part of her ongoing project, Waiting Wars.

It was inspired by her visit – during her residency in the Netherlands - to a Unesco World Heritage Site called Fort bij Vijfhuizen that was built to defend Amsterdam from an enemy that never came.

In response to this, and in the context of soaring military spending in Europe, she created the first chapter of Waiting Wars, looking at the fort’s history in the context of the colonial past of the European Union.

And then there’s Andreas Mallouris, from Cyprus, where the legacy of British rule remained beyond independence in 1960 and homosexuality was illegal until 1998.

He was keen to explore the dissonance between the more progressive LGBTQI+ laws and attitudes and those relating to queer people seeking sanctuary in the UK.

In Newcastle he spent time with queer gardening club TopSoil which inspired him to establish a new gardening initiative for sanctuary seekers in Nicosia.

Andreas’ work encompasses sculpture, drawings, videos and performance.

Clymene Christoforou said: “In a world of protectionist national policies, cuts to international development funds and mainstream political rhetoric stoking division, we more than ever need conversations that navigate harmful and polarising acts and their far-reaching consequences.

“The Contested Desires artists create bridges for us to reflect on how our contemporary culture and society is entangled with the power play and complexities of Europe’s colonial past.”

Malavika Anderson, manager of GNM: Hancock, added: “Now, more than ever, it is crucial for us to reflect on and question our shared histories and their implications in today’s world.

“It felt very important for us to present this work in our museum, surrounded by objects and collections that in many ways symbolise the very questions that the artists have been working with.”

The Contested Desires exhibition runs at Great North Museum: Hancock until Tuesday, July 29.