Exhibition highlights wonders and ills of our oceans

Baltic artists sound an alarm

Art and science have long been treated as uneasy bedfellows, kept apart in school curriculums as if the one had nothing to offer the other.

But Baltic’s new Level 4 exhibition shows that’s nonsense.

Here you can hear an artist interviewing a marine biologist about the decline in fish stocks off Hartlepool.

You can learn how a rock – actually a polymetallic nodule – from the Pacific Ocean has challenged assumptions about life on earth.

And you can do so amid things of beauty.

The exhibition is called For All At Last Return, a phrase taken from a book by marine biologist Rachel Carson called The Sea Around Us, and it’s the answer to a question curator Emma Dean asked herself after seeing rubbish on a beach and learning of the sudden die-back of North East marine life.

How could contemporary art address the fragility of marine eco-systems?

Work by 12 artists from around the world features in this impressive exhibition and there’s a lot to see and learn from – and to enjoy.

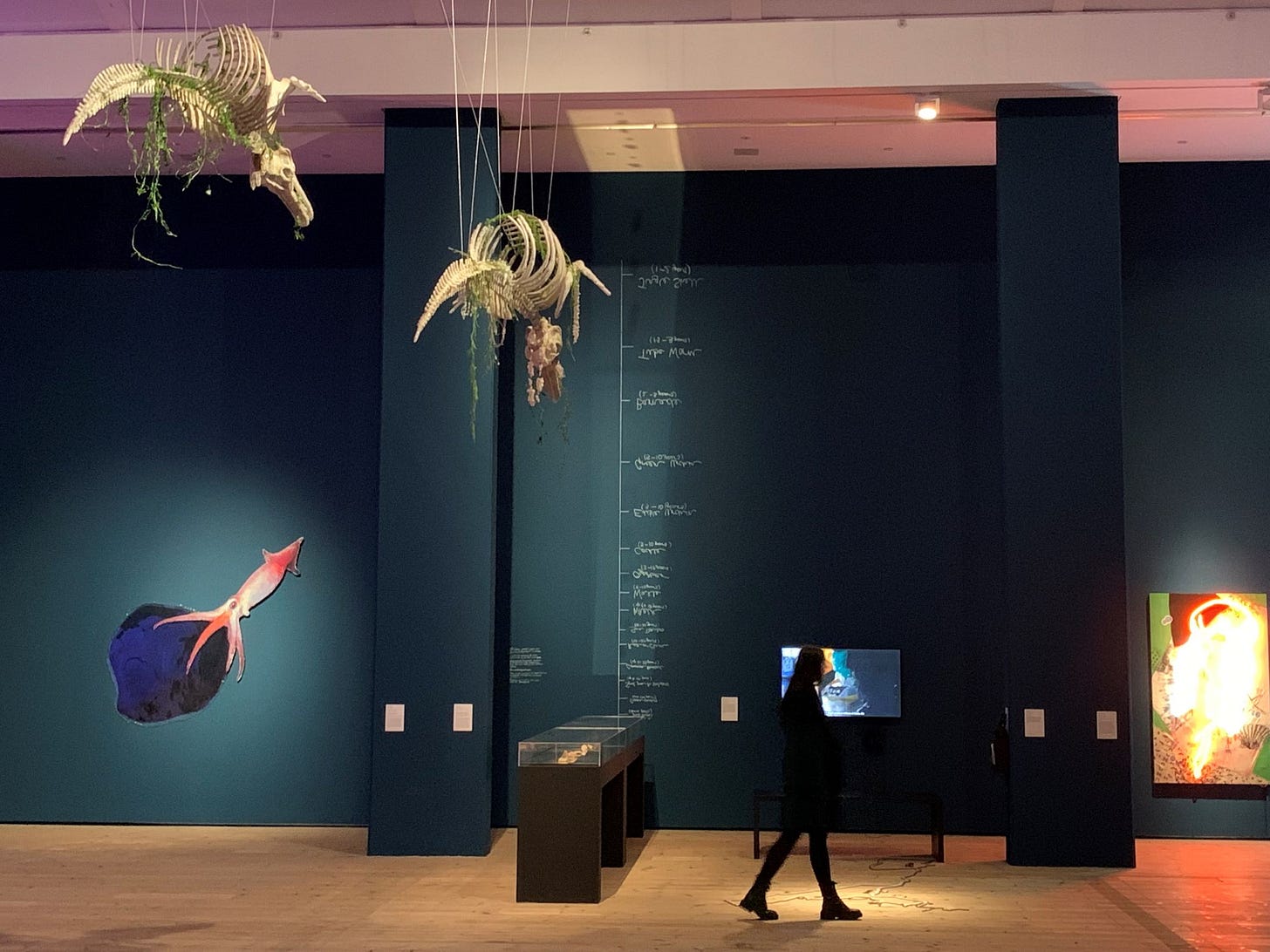

A film by American video and performance artist Joan Jonas appears to show her fraternising with a giant crustacean.

A shimmering tapestry by Nigerian artist Otobong Nkanga shines a light on the ocean’s darkest depths.

Londoner Shezad Dawood’s coral reef sculptures rest on the floor beneath dangling model skeletons of threatened dolphin species by Bianca Bondi, from South Africa.

Coinciding with the COP 30 climate change conference, it’s a timely reminder of the importance of our seas and oceans and the damage we do to them.

Two of the artists represented are from the North East and both of them are fully engaged with science.

Rob Smith, originally from Worcestershire, started out studying biology, chemistry and physics at A level while doing art in free periods. He then dropped physics in favour of religious studies and went on to study sculpture at university.

He moved to Whitley Bay 11 years ago when embarking on PhD studies at Northumbria University.

Setting up at Baltic, he explained: “I call myself an artist but I have the privilege of being part of a research group called Visualising the Deep Sea in the Age of Climate Change which is based at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology in Trondheim.

“It gives me access to a really broad group including marine scientists, technologists, media theorists and other artists. It opens up wide-ranging conversations.”

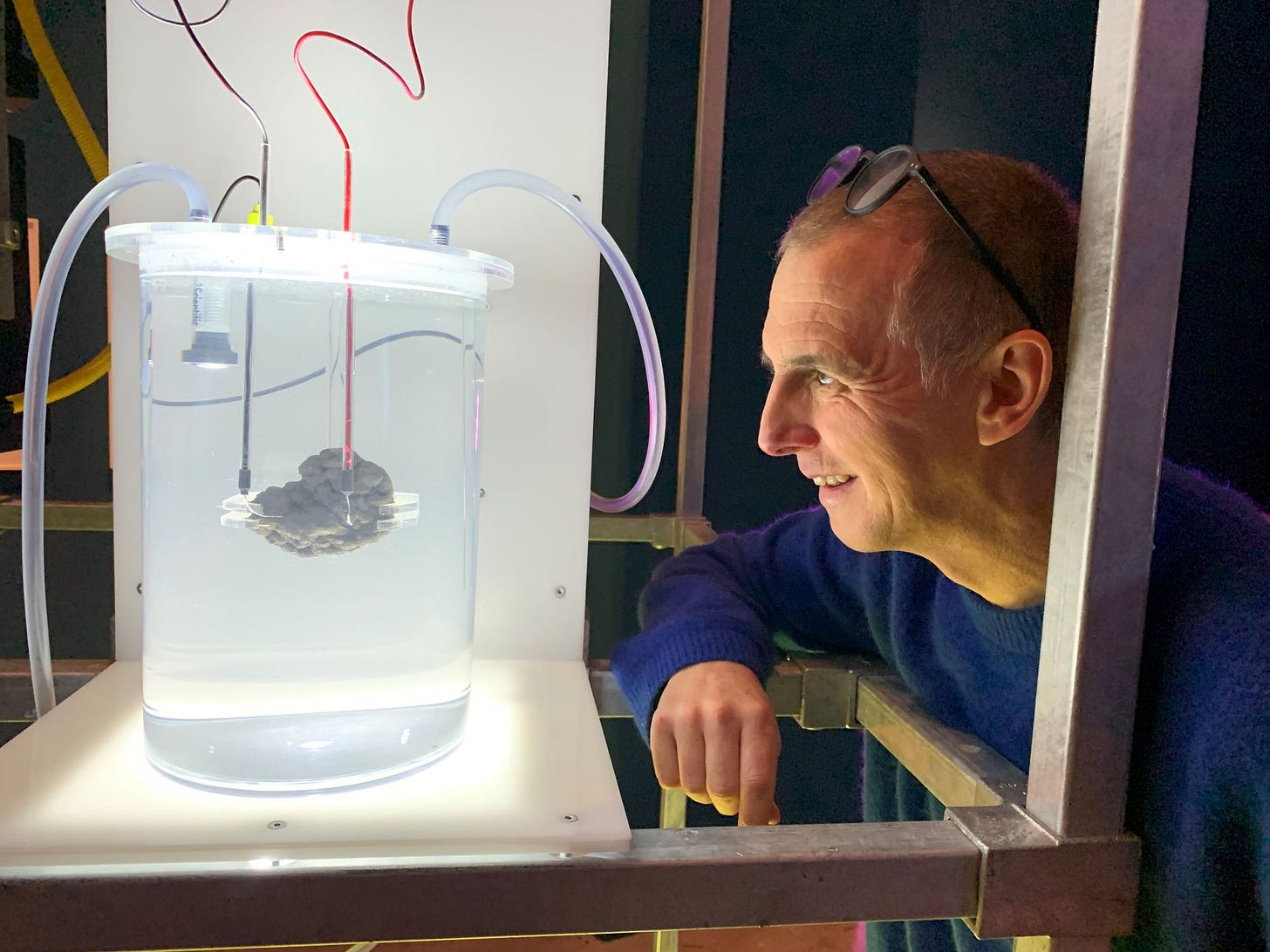

Rob was fine-tuning an exhibit that might have looked more at home in a lab although it was throwing pretty patterns on the floor. This was his Galvanic Lander, a complex creation with a story to tell.

Rob explained his fascination for life in the deepest oceans and particularly the discovery by Prof Andrew Sweetman, of the Scottish Association for Marine Science, that rock-like polymetallic nodules on the Pacific Ocean floor emit what he has termed dark oxygen.

“It’s a source of oxygen in the dark ocean that nobody knew about before,” said Rob.

“It suggests there’s oxygen sustaining life in this deep sea ecosystem so if you remove all the nodules it could have a devastating effect.”

The nodules, first discovered in the 1870s by scientists aboard HMS Challenger, which embarked on an epic voyage to gauge ocean depths, contain rare earth metals of interest to deep sea mining companies.

Rob spent time with Prof Sweetman who explained how he had conducted experiments remotely, dropping metal structures called landers from a boat and letting them descend 4.5 kilometres to the ocean floor.

Having completed its task, the lander would signal to those above and release a weight in order to resurface.

Rob explained a moral dilemma, that the rare earth metals are useful in the move to green technologies as components in wind turbines, solar panels and heat pumps.

“In some sense there’s a need for these metals but mining companies want to extract them from an environment we know little about.

“If you removed all the nodules it could have a devastating effect not just on the mining site but on the wider ecology.”

Rob’s Galvanic Lander, mimicking Prof Sweetman’s creation, combines ancient and modern.

In a jar of sea water, precisely matching the saltiness of the deep ocean, resides a nodule attached to platinum electrodes which monitor the oxygen-producing electrical current it emits.

The amount of oxygen produced, converted into data, is shown on a monitor. It was currently registering 355 millivolts.

“Not bad for a small rock,” enthused Rob. “That’s about a quarter of an AA battery. And you’ve got to remember there are millions of square miles of these on the sea bed.”

The monitor responds to other data feeds, including sea temperatures (generally on the rise since the Challenger voyage) and the share price of one of the biggest deep sea mining companies, based in America.

This is up from $1.94 per share in April to a startling $9, the result, said Rob, of President Trump’s executive order known as Unleashing America’s Offshore Mineral Resources.

According to Rob, this gives the green light to deep sea mining companies to bypass safeguards imposed by the United Nations and the autonomous International Seabed Authority.

Prof Sweetman and others like him are deeply concerned.

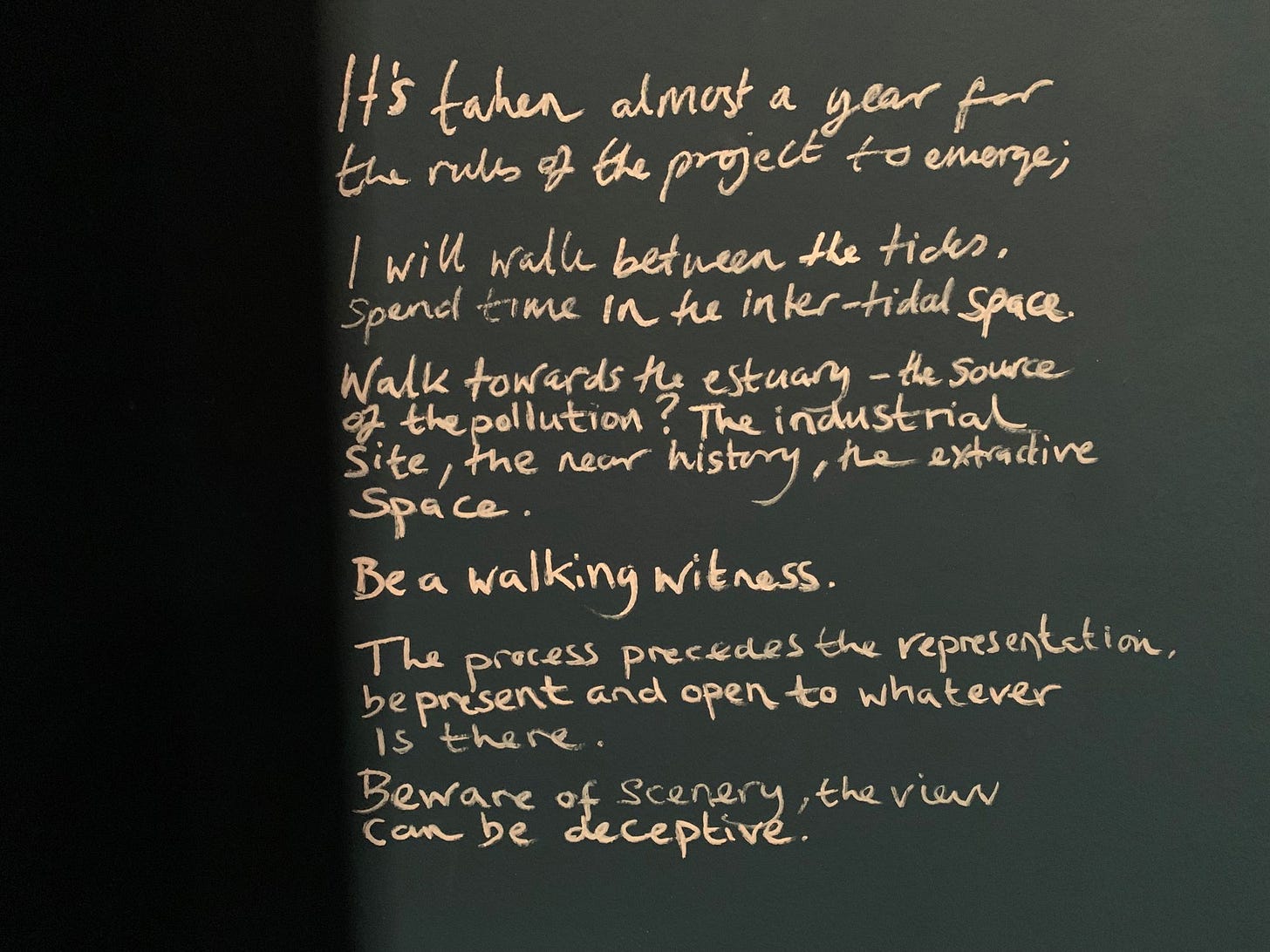

Another North East artist with an interest in marine science is Michele Allen whose piece called Timeline (lifeline) alludes to painstaking work she has done around the Tees Estuary.

She has worked closely with communities and academics to understand the challenges posed by polluted water and the effects of that sudden mass die-off of marine species in 2021.

Her Baltic installation incorporates objects gathered over an 18-month period when she walked along 40 miles of coastline.

You can listen to her fascinating interview with marine biologist Dr Gary Caldwell about the importance of North East fishing communities in sustaining marine ecosystems.

Fishermen with detailed knowledge of coastal waters he likens to canaries in the coalmine, being the first to spot alarming anomalies while having a vested interest in preserving fish stocks.

Things have become very bad, he tells Michele. A Hartlepool fisherman, in a sea area where quite recently he would have expected to catch up to 20 boxes of fish, recently netted just nine individual fish over several hours.

Having continued fishing not to make a living but just to preserve his mental health, he now planned to sell his boat. That, says Gary, means one less coal mine canary.

While generally pessimistic, he concludes on a positive note, hoping recent moves involving Northumbrian Water can help to restore a barren sea area to some degree of health, perhaps with seaweed farms and oyster beds enabling fishing communities survive.

Emma Dean picked up on the note of optimism, saying the exhibition dealt with realities but there was a message of hope. “It’s about regeneration and resilience,” she said.

For All At Last Return is at Baltic Centre for Contemporary Art until June 7, 2026 – along with another fabulous exhibition, just opened on Level 3, by film-maker Saodat Ismailova called As We Fade.