Book uncovers stories of life inside Newcastle’s lost prison

It is 100 years since Newcastle prison closed and a new book reveals what life was like within its towering walls. Tony Henderson reports

A century ago the doors of Newcastle Prison, through which an estimated 250,000 unfortunates had passed, closed for the last time.

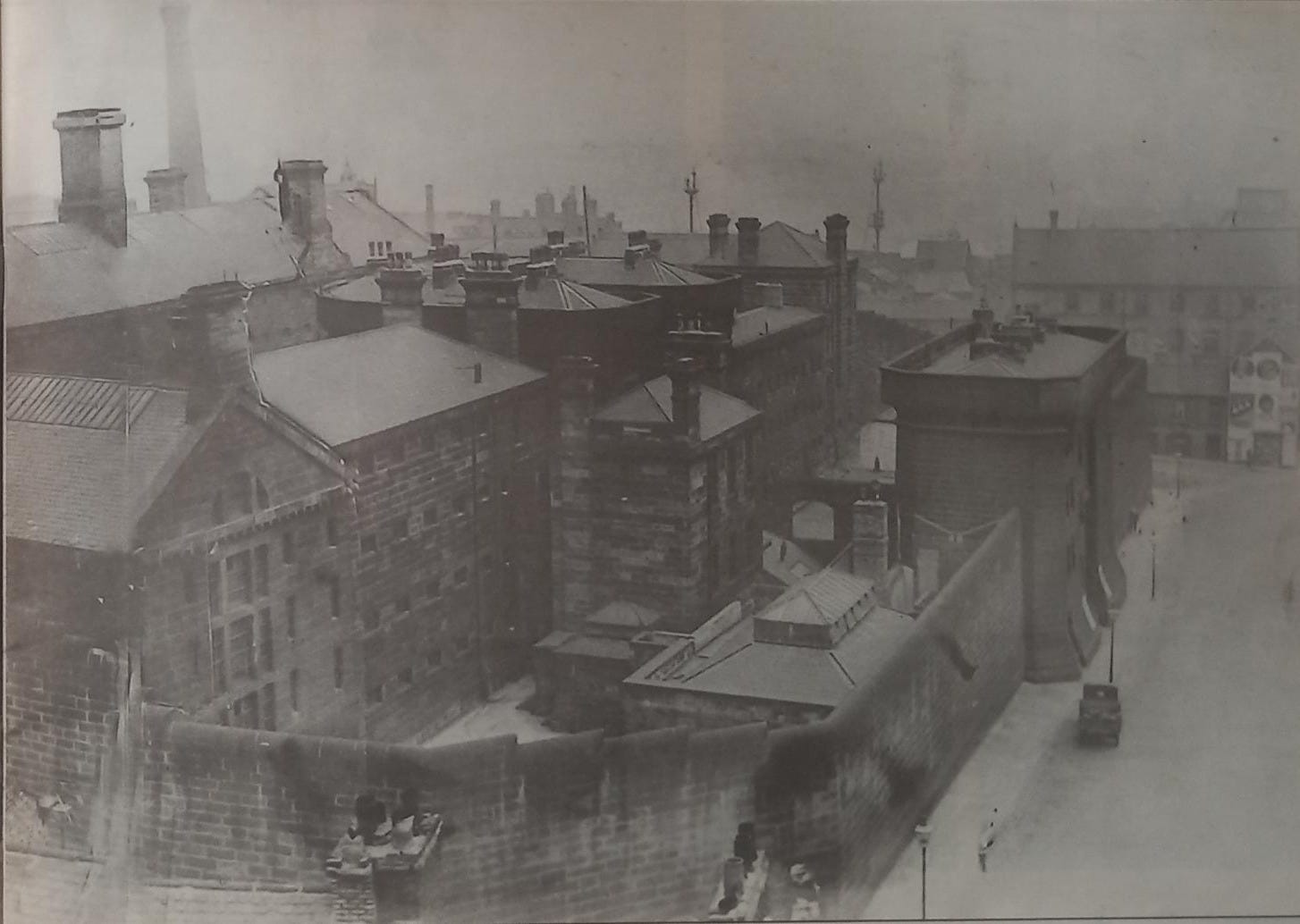

The gaol, east of Pilgrim Street in Carliol Square, had opened in 1828 and was described as having the appearance of a fortress built to withstand a siege.

The jail was designed by leading Newcastle architect John Dobson, a commission in stark contrast to his Central Station, Royal Arcade and a series of Northumberland mansions.

Dobson was nothing if not thorough and while working on his design consulted well-known burglars to glean information on how they had escaped from jail.

Now to mark the centenary of the prison’s closure, a book based on years of research has been produced which details how the jail functioned, the life inside its walls led by inmates and staff, and the remarkable stories the place generated, including escapes and executions.

Newcastle Prison: A History 1828–1925 is from Tyne Bridge Publishing at £14 and available to buy at Newcastle Libraries.

The book is built on the work of four co-authors - Dr Patrick Low’s PhD at Sunderland University was on capital punishment in the North East and Dr Shane McCorristine is a Reader in Cultural History at Newcastle University, specialising in the history of crime. Both combined to create a website on Newcastle Prison.

Dr Helen Rutherford is a solicitor and associate professor in Northumbria University’s Law School with research interests in the 19th-century role of coroners, crime and trials and punishment with a North East focus.

Dr Clare Sandford-Couch is also a solicitor and an associate lecturer in the Law School at Leeds Beckett University, who has published on criminal legal histories in the North East. She is currently researching policing and detection in 19th-century Newcastle.

Although opened in 1828 to some fanfare, Newcastle Gaol became infamous for its overcrowding - a prisons issue which persists today. By the time the jail closed in 1925, it was judged to have been a failure and no trace of it remains.

Men, women and children endured a harsh environment which could include severe punishment - another debate which still surfaces today.

It was also the scene of 16 executions. On an October night in 1925, the bodies of 12 executed men were moved from their burial plots in the prison yard to All Saints cemetery in Jesmond. The last executions were of two men on November 26, 1919.

Prisoners were locked up for often minor offences of theft, drunk and disorderly, fraud, and debt. The jail also housed suffragettes, some of whom were force-fed through the nose after going on hunger strike.

The prison took almost five years to build, with the foundation stone being laid by Mayor Robert Bell in 1823. A brass plate with details of the event was fixed to the stone and is now in the care of North East Museums.

In his speech the Mayor spoke of the hope of the building improving the health and morals of the inmates. But he did not add “their comfort” as he saw no reason why criminals should enjoy comforts “which are beyond the reach of many honest and industrious persons”.

The cells were 25ft square and most rooms were unheated, and work for many men included breaking stones or the treadmill. It was not until 1840 that boys were held separately from the men.

Prisons like Newcastle were built near to town centres to act as a visual deterrent for those contemplating crime. Inmates in Newcastle could hear children playing in the yard of the Jubilee School, just 26 ft (eight metres) from the walls.

In 1858 prison chaplain John Irwin described the interior of the jail as a “paradise of thieves, a nest of villainy, a hotbed of vice.”

Punishment for women included wearing a muzzle and for men it could be flogging. In 1872 reporters were invited to witness a flogging when 18 lashes were delivered.

In 1863 twelve boys convicted of stealing apples, carrots and slippers received between six and 12 lashes of the birch.

Offending prisoners could also be confined to a dark cell, where complete darkness and silence were imposed, often for several days, with a diet of bread and water.

Prison governor Thomas Robins said: “I have no sympathy with those who would make a prison anything but a disagreeable place.”

Women made up around a third of inmates in 1865–66, with some taking their children into jail with them.

There were escapes, with on one occasion four men scaling the walls using ropes made from torn bedding. Two reached Carlisle, pursued and then captured by Gateshead police chief John Elliott.

He was known as “Clencher” Elliott, and such was his fame music hall songs were written about him.

When the prison closed, a public auction of 800 lots was held in the exercise yard. Items included two organs and an altar from the chapel.

Stone from the demolished jail was used to support the foundations of the new Tyne Bridge.

A telephone exchange was built on the site of the prison, which has had a number of uses including dance studios, a tattoo parlour, and the World Headquarters nightclub.